Medieval views on Holy Days and Relaxation

It is the beginning of August. Time for rest and relaxation: a holiday. The word holiday is literally derived from the Holy Day, when people had the day off to participate in a religious festival.

Holidays, especially true Christian Holy Days, are under pressure today, as they considered to be bad for the economy. Why should people have two days off for something like Pentecost, a feast people don’t even know the meaning of anymore, or for Ascension day? Interestingly, this is not a new debate at all. Medieval employers were very like their modern-day counterparts.

Holidays and the sin of Sloth

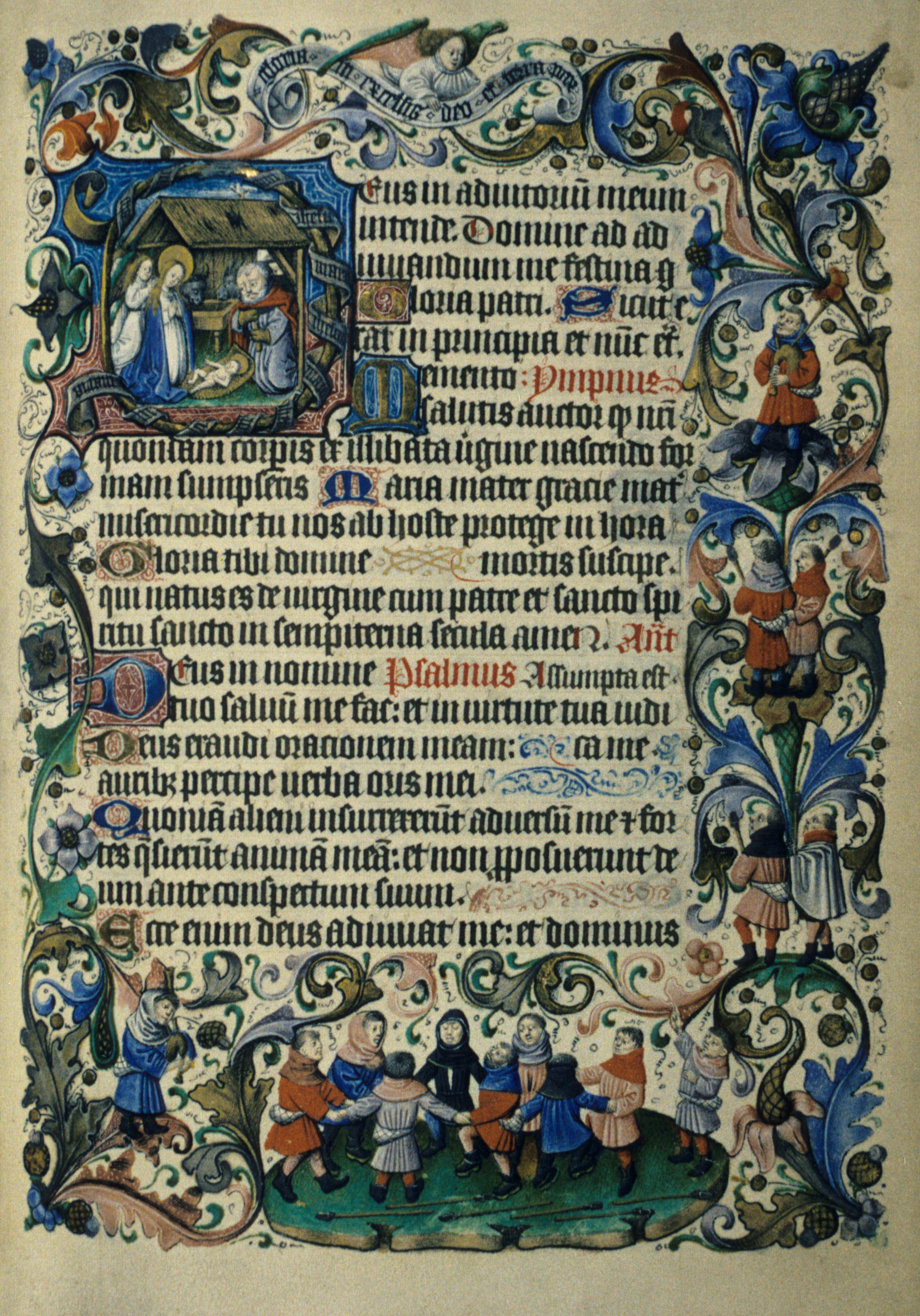

In the Middle Ages there was a considerable number of Holy Days, so much so, that the landowners complained that their peasants were not doing enough work. Moreover, peasants allegedly misused their Holy Days by not going to church to hear mass and thank the Lord, but by taking the day off to celebrate (dance, drink and eat) instead. Therefore, in the employers’ view, the number of Holy Days needed to be restricted. This view is reflected in their lavishly-illustrated prayer books and psalters. In depictions of the nativity of Christ, rather than listening to the angel who is announcing to them the birth of Christ, the shepherds are shown dancing and frolicking, as in the 15th-century Hours of Yolande of Lalaing (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce 93). Spending one’s holiday in this way was categorized as Sloth (acedia), one of the seven deadly sins.

Although Sloth could be understood in a spiritual sense, i.e. the failure to perform one’s duty and obligation to God and to be indifferent to others, Sloth could also be taken in a more communal sense, a failure to help out fellow citizens by performing the works of charity. Maybe this is why a personification of Sloth is shown as one of the corbels supporting the vault of the entrance passage into the courtyard of the 15th-century Brussels town hall. We see a voluminously dressed lady placing her head on a fine cushion.

A lady with a cushion

The cushion under the lady’s head is a characteristic symbol of Sloth, to be found in a number of representations of the vice. One occurs on a tabletop of circa 1500-1515 in the Madrid Prado, showing Sloth as a man sitting upright on a chair with a cushion behind his head. A panel showing the virtues and vices in the Antwerp Maagdenhuis Museum renders Sloth as a man sleeping in bed with his clothes on and a large pillow under his head, while a devil covers him with a blanket. Cushions also feature on Pieter Brueghel’s engraving of the vice of Sloth, dated 1557.On the bottom left of the image a man is lying on his back, eating, while his bed on wheels is being pushed around. An enormous pillow supports his head. Behind him is an inn where two devils offer a cushion to a young woman who is sitting at a table looking bored. In the middle of the composition a woman is resting on a sleeping donkey, while her head is supported by a giant pillow from underneath which a devil emerges. No wonder the Dutch have a saying: ‘een leegh mensch is een duyvels oorkussen’ (a lazy person is the devil’s pillow).

The best parallel for the Brussels corbel is to be found on fol. 181r of a manuscript Hugo von Trimberg’s ‘Der Renner’ (The Horseman) in Leiden’s University Library, showing Sloth as a lady riding an ass with a devil placing a large pillow behind her head. Hugo von Trimberg was born around 1230 in Wern(a) and died sometime after 1313 in Bamberg, where from 1260 to 1309 he had been rector of the collegiate church of St Gangolph. This was unusual as Hugo was not a cleric but a family man with a wife and children. Hugo wrote various treatises in Latin for the use of preachers, as well as saints’ lives and a manual with summaries and short biographies of the best known Latin authors. ‘Der Renner’, written between 1296 and 1313, is a treatise about the seven deadly sins, hôchfart, gîtikeit, frâz, unkiusche, nît, zôrn und lâzheit and the types of person prone to succumbing to or the sort of behaviour characteristic of each sin and these are discussed through exemplary tales, stories, allegories and fables. It is his only surviving work in the German tongue (we know of four others) and is considered to be his ‘magnum opus’. With 26.611 verses it is the longest moralizing didactic poem in German. Von Trimberg wrote it in German so that its content would be accessible to the general public. It exists in various manuscripts, attesting the work’s popularity in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Slackening the bow

Luckily for us, even in the Middle Ages there were also those who advised relaxation and among them not the least of saints and scholars. Their role-model was Saint John the apostle, who, according to the 6th-century author Cassiodorus, whose account was recorded in Jacobus de Voragine’s 13th-century Golden Legend, had been given a partridge in which he took great joy. The saint held it in his hands, stroked it and played with it, when one day a young man passed by who made fun of him, saying he was wasting his time and was acting like a child. St John replied by asking the young man what he had in his hand and for what purpose. The young man replied it was a bow used for shooting birds and animals. The apostle then asked him to demonstrate this and the young man bent his bow. When the apostle went on stroking the bird and said nothing, he slackened his bow. St John then asked him why he did that, to which the young man replied that holding the bow bent would weaken it. And this is where St John explained that is was likewise with man. If he had to work all the time, he would weaken. A man therefore needed relaxation once in a while to acquire new strength, in order to do better.

Echoing Aristotle’ Nicomachean Ethics Thomas of Aquino (c. 1225-1274) held that recreation and pleasure were means leading to virtuous behaviour as well as physical health. He thought it “proper for a person to amuse himself for a time so that later he may work harder. The reason is that relaxation and rest are found in amusement. But, since men cannot work continuously, they need rest. Hence it is clear that amusement or rest is not an end because this rest is for the sake of activity in order that afterwards men may work more earnestly”.

So for now, I would say, pillows up, so we can all start again refreshed at the beginning of the semester.

© Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.