ʿAṭṭār, Khayyām & Ghazāli: Scholars of the Past, Influencers of Today?

In the whirlwind of modern life and the ceaseless march of technology, universities and prospective students grapple with the question: do classical works still resonate in our contemporary world?

In the whirlwind of modern life and the ceaseless march of technology, universities and prospective students grapple with the question: do classical works still resonate in our contemporary world?

The study of classical works in any culture is crucial for preserving heritage and understanding the evolution of scientific knowledge. These texts provide invaluable insights into the nuances that have shaped modern science and knowledge, and by examining these works, researchers can uncover the influences of historical events, social changes, and cultural interactions on the understanding of the world as well as revealing the values, beliefs, and daily lives of people from different historical periods. Spanning genres such as literature, philosophy, religious scriptures, and historical accounts, preserving and studying these texts is essential for maintaining cultural continuity, as they underpin modern cultural practices and identities.

Despite their enduring value, classical texts often elude comprehension by native speakers and descendants of the language, whose engagement with modern digital media underscores the perceived irrelevance of ancient literature. The fast-paced, visually driven nature of contemporary content exacerbates this disconnection between contemporary society and classical literature, particularly for works from foreign cultures. Can classical works, thus, undergo adaptation to contemporary norms and seamlessly integrate into the fabric of popular culture? Addressing this seemingly formidable challenge, may prove manageable through a comprehensive understanding of these classical works whose substance endures and transcends temporal and geographical borders.

The Big Bang Theory, an American sitcom

The Big Bang Theory, an illustrious contemporary sitcom that graced screens from 2007 to 2019, orchestrates a symphony of erudition and enculturated quirks. Set in Pasadena, California, the narrative primarily converges upon the characters' vocational aspirations and the concomitant tribulations associated with their interpersonal discourse. The series scrutinises the nuances of camaraderie, romance, and personal evolution against the backdrop of intellectualism and subcultural esotericism. These protagonists’ insatiable curiosity for scientific phenomena and unquenchable desire to unravel the mysteries of the universe serve as metaphors for the human quest for understanding and meaning in a complex world. It seems, therefore, quite ordinary that the show, due to its intellectual nature, deftly integrates a profound intellectual dimension by frequently interweaving references to well-known Western philosophers, scholars, and scientists. Let us consider two examples.

Sheldon, an atheist, suggests celebrating Newton's December birthday instead of Christmas, sparking a debate over Jesus' birth timing and the holiday's pagan roots. This juxtaposes scientific and religious ideologies.

In Season 4, Episode 8, Sheldon uses Schrödinger's cat theory to advise Penny on her romantic dilemma. These references highlight the characters' intellect and prompt viewers to contemplate philosophical and scientific concepts shaping their worldviews.

The show frequently references luminary scholars like Isaac Newton, Stephen Hawking, and Albert Einstein, enhancing its intellectual and comedic appeal. Persian scholars, though less common, also feature, particularly from the classical period. Persian thinkers like Avicenna (d. 1037) and Rumi (d. 1273) have influenced Western culture, appearing in literature, television, and cinema and musical spheres. However, despite their enduring relevance, other classical Persian scholars are rarely referred to in Western popular culture.

Three Persian Classical Scholars

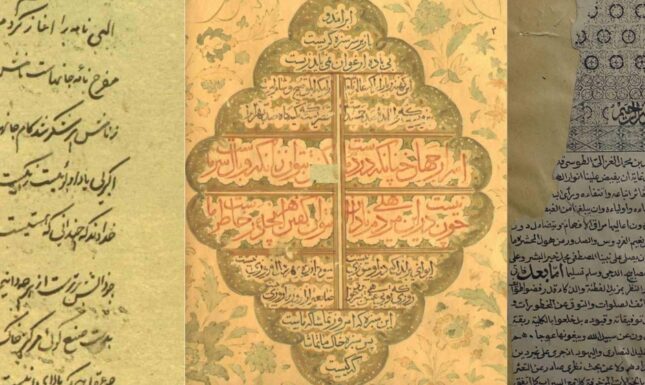

ʿAṭṭār: This too shall pass!

In a scene in Series 07 Episode 20 (The Relationship Diremption), Sheldon and Howard are trying to comfort each other in the cafeteria at work about previous embarrassing actions whose shameful consequences they must now face:

The above bold phrase is narrated in a story by a Persian poet and mystic Sheikh Farid al-Din ʿAṭṭār (1145-1221), from Nishapur, Iran. His celebrated works, Manteq al- ṭayr "The Conference of the Birds," is regarded as the zenith of mystical poetry, a tapestry of profound allegory narrating the pilgrimage of birds through seven valleys of mysticism in search of their spiritual sovereign (see Davis and Darbandi (2011) for the translation of the work). This allegorical voyage serves as a profound metaphor for the soul's relentless odyssey toward celestial union, embodying the quintessence of Sufi doctrine with its themes of divine love, self-effacement, and transcendence of the ego.

The phrase "this too shall pass" in the show’s dialogue is taken from the Elāhi Nāma (Book of God), a mystical allegory by ʿAṭṭār. It is an expression of the transient nature of all things in life, a concept deeply embedded in various philosophical and spiritual traditions, whose roots can be traced back to ancient wisdom including Buddhist philosophy and Stoicism, Taoism, and Sufism, amongst others (see, for instance, Chödrön (2002), Chuang (2002)). In the context of ʿAṭṭār's work and Sufism, the phrase is linked to the idea of detachment from the material world and the recognition of the ephemeral nature of earthly pursuits. This philosophy can be aligned with the concept of fana, which refers to the annihilation of the self and attachment to worldly desires in favour of spiritual realisation and union with the Divine. Interestingly, impermanence employed in the phrase invokes the same ethical lesson regarding all things, whether pleasurable or painful, which are subject to change and eventual cessation.

Omar Khayyām: The moving finger

In Season 3, Episode 16 of the show, Sheldon's court appearance for a driving violation, while helping Penny, prevents him from attending a comic book signing featuring Stan Lee. Frustrated by missing out, he vents his disappointment at Penny, regretting his inability to enjoy the event alongside his friends.

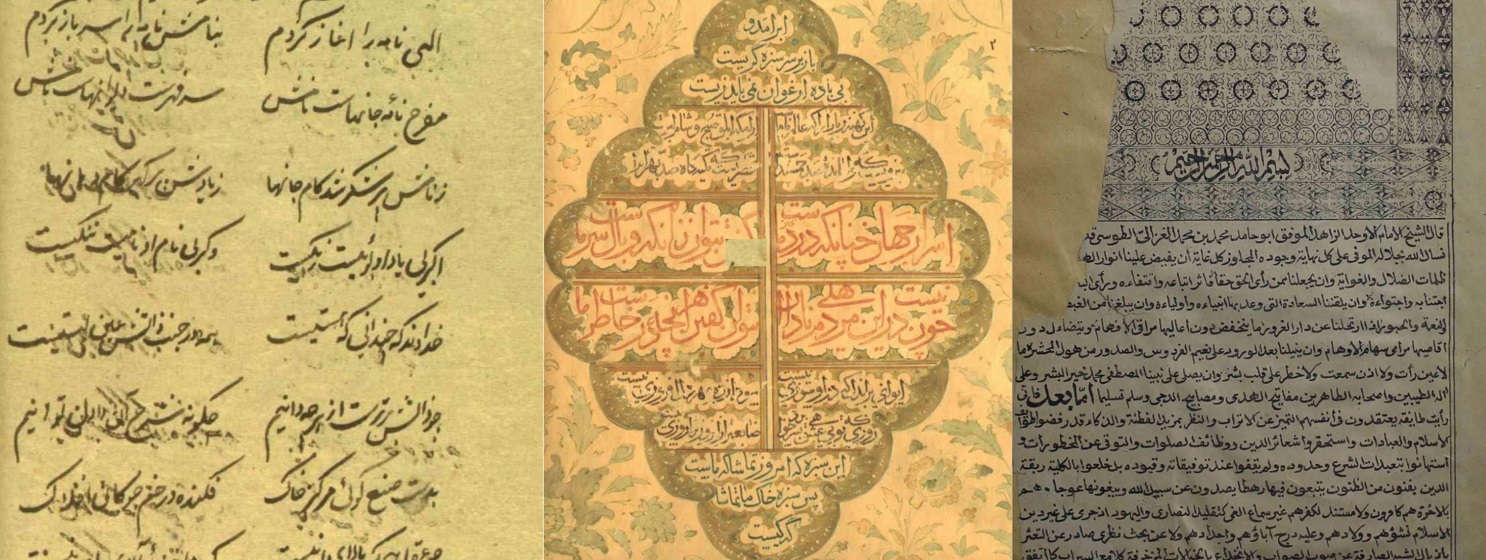

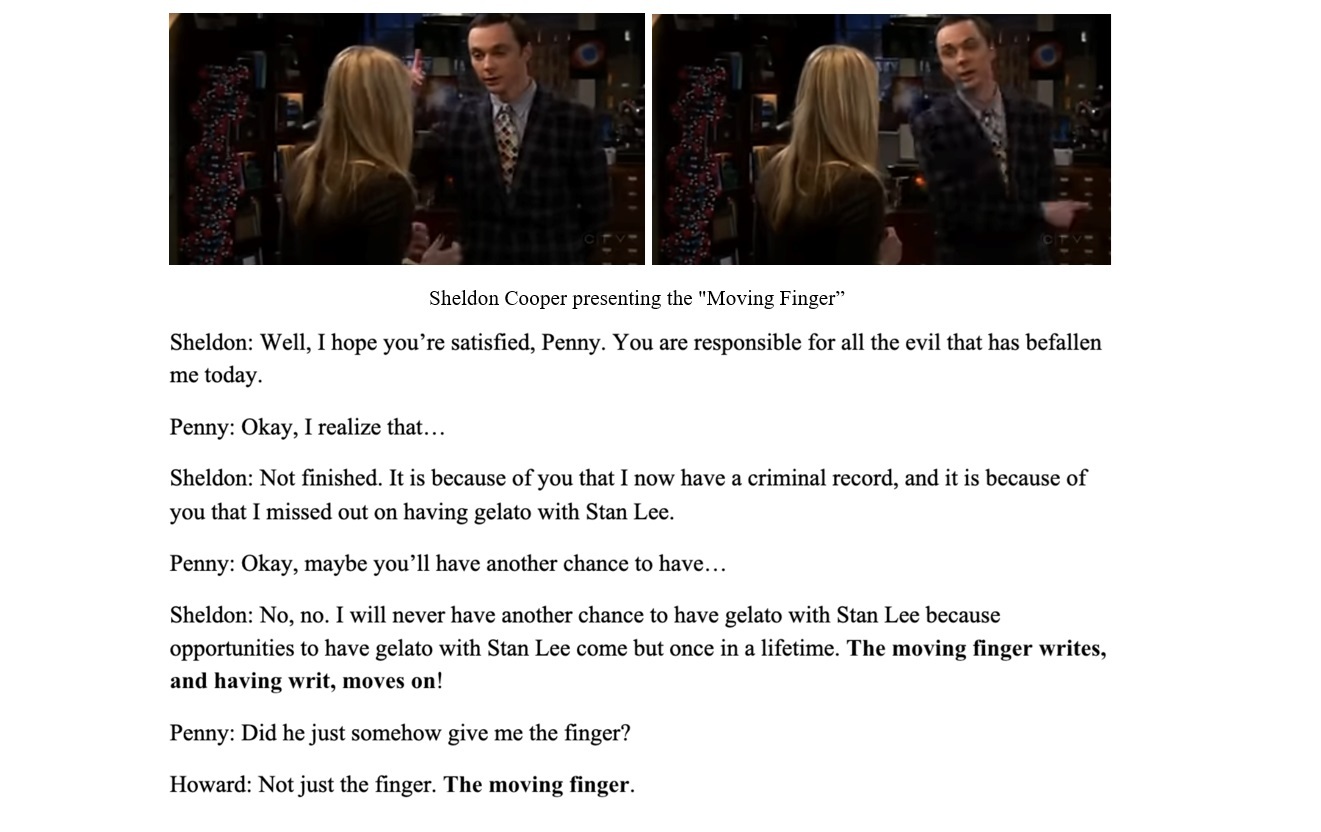

Omar Khayyām (1048-1131) was a polymath from Nishapur, Iran, venturing into the realms of mathematics, astronomy, and poetry. His mathematical prowess yielded substantial advancements in algebra and geometry. However, it is his poetic magnum opus, The Rubāʿiyāt, that remains etched in the annals of literature. It consists of a collection of quatrains, each offering a glimpse into Khayyām's contemplation of life's mysteries. Khayyām's verses explore the pursuit of hedonistic pleasure amidst the enigma of existence, casting a nuanced existentialist hue.

Khayyām's poetic resonance has transcended linguistic boundaries, with translations into numerous languages FitzGerald's English. translation, in particular, catapulted Khayyām's poetic philosophy into the English-speaking world, achieving the status of a classic in English literature and stoking profound admiration for Persian poetry, even surviving the Titanic disaster (see also Shepherd, 2001 and Marks, 18 May 2023).

The quote in the series is taken from the following Fitzgerald’s translation:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

In these verses, Khayyām invokes a striking allegory, wherein the hand of destiny assumes the form of a celestial calligrapher, inscribing the chronicle of human existence. The vivid imagery of the "Moving Finger" conveys a compelling impression of fate as a capricious, yet inexorable, force, akin to an impartial chronicler recording the human lives, encapsulating themes of fate, determinism, and the passage of time, some recurring motifs in Khayyām's poetry. The quatrain delves into profound existential questions, highlighting the notion that once events unfold, they defy human intervention. It underscores determinism, where occurrences are seen as preordained inevitabilities beyond human control. Khayyām meanwhile acknowledges human agency, suggesting that while fate shapes the narrative, individuals influence its trajectory through their choices. Additionally, Khayyām's poetry reflects on the relentless passage of time, symbolised by the "Moving Finger," prompting reflection on the transient nature of life. This dialectical exploration of fate, human action, and temporal flux invites readers to ponder the complexities of existence.

Ghazāli: The tale of a man and two dates

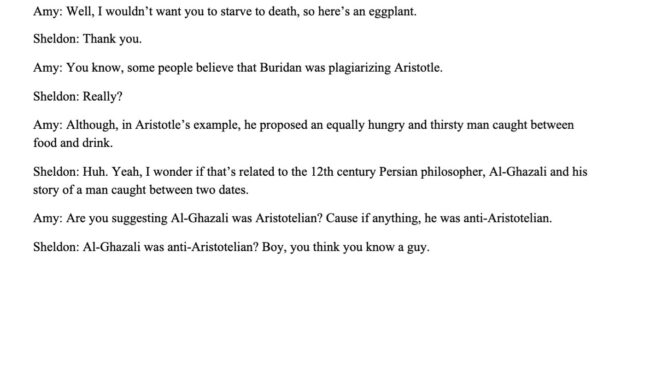

In Series 10 Episode 07 (The Veracity Elasticity), Sheldon, a creature of habit, cohabits with his girlfriend, Amy, who under the guise of a scientific experiment, has lured him into participation Sheldon wonders whether to continue with the arrangement. While standing between the two apartments in the corridor, Amy arrives, and the following conversation ensues:

The conversation alludes to a thought experiment by Ghazāli (1058-1111). His wide-ranging intellectual contributions span philosophy, theology, jurisprudence, and mysticism. His various works, such as Ihyā’ Ulum al-Din "The Revival of Religious Sciences," delves into the moral and spiritual aspects of Islam.

Ghazāli's critique of Aristotelian philosophy, notably in Tahāfot al-Falāsefa, "The Incoherence of the Philosophers," reshaped discourse on faith and reason, leaving an indelible mark on Islamic philosophy, continuing to influence contemporary discussions on the intersection of faith and reason in philosophical discourse.

Causality and Divine Will

At the epicentre of Ghazāli's critique lies his categorical repudiation of Aristotle's conception of causality. Ghazāli asserts that the Aristotelian paradigm of causality, which connotes a deterministic cosmos governed by immutable natural laws, stands in stark contravention to the Islamic tenet of God's unequivocal divine will.

Ghazāli's thought experiment, elucidated in his critique of Aristotle's philosophy, counters deterministic views. In Aristotle's analogy, an equally hungry and thirsty man caught between food and drink should be expected to starve to death if natural causes were not involved. This deterministic view in turn implies predictability. In Ghazāli's thought experiment, a man between two dates (see Marmura’s (1997) translation of Tahāfot al-Falāsefa, 23-24), Ghazāli argues identical scenarios may yield different choices due to free will or divine intervention, aligning with a faith-centric theology. He challenges Aristotle's deterministic universe, asserting God's absolute divine will transcends natural laws. This theological stance diverges from Aristotle's deterministic causality, emphasising the role of free will and divine intervention, pivotal in Islamic belief.

By using this simple thought experiment, Ghazāli vehemently contends that God's divine volition transcends the fetters of natural causality, rendering divine interventions and miracles conceivable, indicating the limitations of Aristotle's causality and determinism in explaining complex human actions, especially those involving choice and intention. It demonstrates his position that divine will and human free choice cannot be entirely subsumed by natural causes and necessitates a reconsideration of the relationship between philosophy and theology.

Eternity of the World and Epistemology

Ghazāli's critique of Aristotle extends to debates on other matters including the Eternity of the World and Epistemology. While Aristotle upheld the eternal universe theory, Ghazāli fervently championed the Islamic doctrine of "creation ex nihilo," emphasising God's role as the Supreme Creator. However, he diverges from the common Sunni interpretation among Islamic Scholars in terms of Ruz-e Alast “the Day of Covenant.” In his discussion of the mention of the Covenant in the Quran (Sura E’raf, Verse 172), he refers to another verse in the Quran (Sura Nahl, Verse 40) based on which he argues that there was no existence before the existence in this world (see Pour Javadi, 2002: 48). As for Epistemology, Ghazāli criticized reliance solely on reason and philosophy for knowledge acquisition. He advocated for mystical comprehension. He staunchly maintained that the apprehension of God and spiritual verities could not be circumscribed within the precincts of reason alone; rather, they require a profound, mystical comprehension wrought through personal experiential insight and intuitive cognition (see also Yasien, 2023), resulting in Ghazāli's extreme contempt for those who feigned Sufism, called an Ebāḥi, (or Ibāḥi) "one who regards everything as permissible” (Nicholson, 1911: 131) issuing a fatwa against them, asking the kings to punish and execute them (see Pour Javadi, 2002: 132). Ghazāli's treatise stands as a monumental censure of Aristotelianism, asserting theological perspectives within Islamic philosophy.

Summary

The contributions of classical figures leave an enduring imprint on society at large. Their writings, widely acknowledged and frequently cited in Iran, permeate educational curricula, and inform everyday discourse through proverbs and anecdotes. In the Western sphere, their works are celebrated and translated, fostering intercultural dialogue. The explicit mention of Persian classical figures, apart from very few exceptions, is not as frequent within Western contexts. The show's blend of humour and intellectual allusions serves to bridge this gap, ensuring the ongoing relevance of their rich cultural legacy worldwide. Classical works thus retain their relevance and viability, as evident from popular culture, by virtue of their enduring and rich content.

Further reading

- Adamson, P. (2002). Al-Ghazālī’s Epistemology. In J. Janssens & D. De Smet (Eds.), A Companion to the Latin Medieval Commentaries on Aristotle’s Metaphysics.

- Bahlul, R. (1992). Ghazāli on the Creation vs. Eternity of the World. Philosophy and Theology 6 (3): 259-275.

- Chödrön, P. (2002). When things fall apart: Heart advice for difficult times. Shambhala.

- Chuang, R. (2002). An Examination of Taoist and Buddhist Perspectives on Interpersonal Conflicts, Emotions, and Adversities. Intercultural Communication Studies 11 (1), 23-40.

- Davis, D. and A. Darbandi (2011). The Conference of the Birds (the translation of the work by ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn). Revised edition. London, England: Penguin Books.

- Kane, R. (2005). A Contemporary Introduction to Free Will. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Marks, P. J. M. (16 May 2023). The ‘Titanic Omar’ preserved for all time (virtually)?, Untold lives blog: Sharing stories from the past, worldwide, The British Library/ India Office Records, https://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlive.... Accessed 30 May 2024.

- Marmura, M. (1997). Translation of Ghazāli's Tahāfot al-Falāsefa 'Incoherence of the Philosophers.' Provo. Utah: Brigham Young University Press.

- Nicholson, R. A. (1911). Kashf al Mahjub: The Oldest Persian Treatise on Sufism by ALI B. ʻUTHAlAN AL-JULLAlU AL-HUJWIRI, translated from the text of the Lahore Edition (lectures in Persian in the University of Cambridge Formerly Fellow of Trinity College and printed for the trustees of the E. J. W. Gibb Memorial), Volume XVII. Leyden: E. J. Brill, Imprimerie Orientals.

- Pour Javadi, N. (2002). Do Mojadded: Pazuhesh-haie darbareye Mohammad Ghazāli va Fakhr Razi (Two Mojaddeds : Studies about Mohammad Ghazāli and Fakhr Razi). Tehran University.

- Shepherd, R. (2001). Lost on the Titanic. London: Shepherds Sangorski & Sutcliffe and Zaehnsdorf.

- Yasien, M. N. (2023). Ghazālī's epistemology: a critical study of doubt and certainty. New York: Routledge.

© Siavash Rafiee Rad and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2024. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Siavash Rafiee Rad and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.