“A pair of apples fashioned in ivory”: Female breasts and the male gaze in Renaissance Italy

[Click here: naked women!] Modern advertising companies often use the female body, and breasts in particular, to attract attention. Renaissance artists and writers were rather preoccupied with the subject too.

The naked body

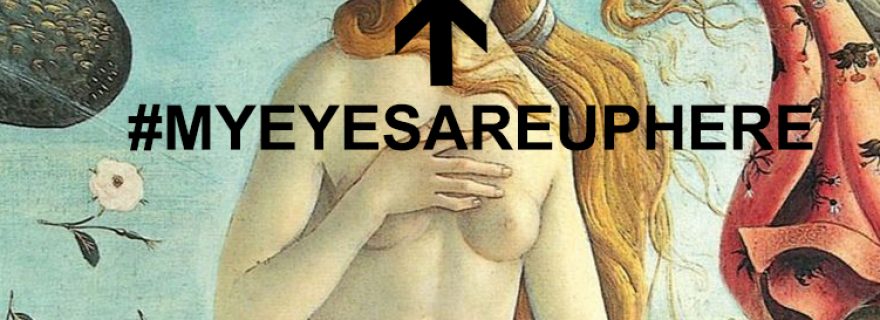

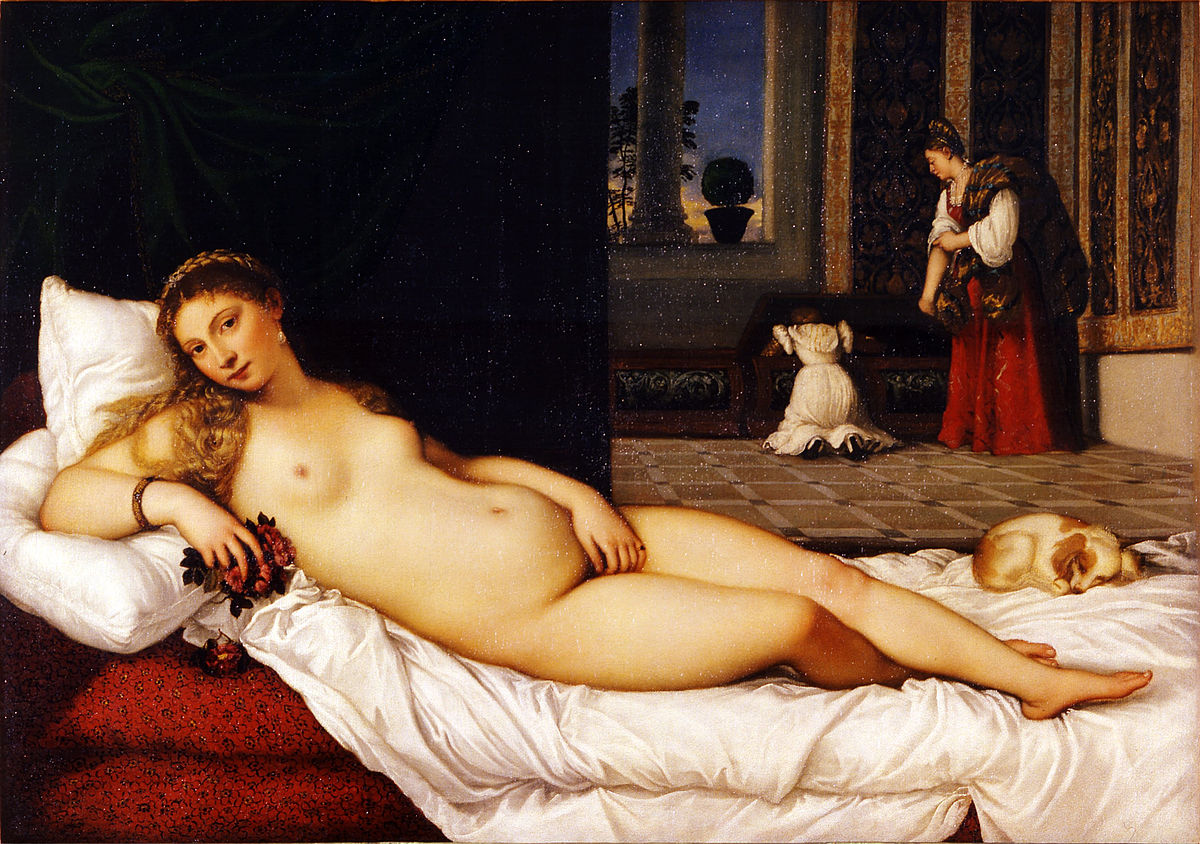

Italian Renaissance art includes numerous beautiful depictions of the naked female body: Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1486) and Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538) are only two of the most famous examples. Although in preceding centuries we can find images of naked women as well, the goals of medieval and Renaissance art differ. In medieval art, naked bodies were not meant to please (or even arouse) the viewers, but rather to warn them to abstain from sin and sexual misbehavior. During the Renaissance, inspired by the example from classical art, artists started to depict naked bodies for their beauty, their aesthetic rather than moral value.

Interestingly, while in visual art we come across as many naked men as naked women (think for instance of Michelangelo’s 1504 statue of David), when we analyze the literature created in Renaissance Italy, the description of the naked body appears to be reserved for women. The authors of romance epics, novella stories and treatises on love rarely if ever muse on the (naked) bodies of men, but many of them include detailed top to bottom descriptions of the female body to their texts whenever the subject allows it. The unbalanced depiction of male and female form in Renaissance literature calls to mind a concept known as “the male gaze”. This phrase, invented by the film critic Laura Mulvey in 1975, represents the way in which visual arts and literature depict the world and women from a masculine point of view, presenting women as objects of male pleasure.

Reclining Venus. Painting by Titian (ca. 1538). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A Renaissance peepshow

Comparable to modern cinema, the male gaze in Renaissance literature often takes the form of voyeurism. Take for instance the two scenes of Ludovico Ariosto’s romance epic the Orlando Furioso (1532), in which a beautiful naked damsel is chained to a rock as sacrifice to a sea monster. These scenes provide Ariosto with the opportunity to describe not only the visible parts of the clothed female body, but also those parts which are “normally concealed by a tunic”, and which the ladies, bowing their heads and trying to cover themselves as best as they can, are unable to cover up.

Although the primary purpose of Pietro Bembo’s treatise Gli Asolani (1505) is explaining the origins and nature of love, one of the narrators in the story, the gentleman Gismondo, elaborates on the female body when he talks about the way in which a male lover looks at his beloved, using the appearance of the ladies in the audience for his inspiration. Moving from the hair, to the forehead, eyes, cheeks, and mouth, he finally describes a very particular set of breasts which the rest of the company immediately identifies as that of the youngest girl in the company, Sabinetta, “since that lovely girl, who for her youth as well as for the heat was clothed in the lightest of materials, revealed two round, firm, unripe little breasts beneath her clinging robe”. The poor Sabinetta is shocked at being stared at like this and Madame Berenice, defending her, reproves Gismondo, calling the lover he describes “a bold observant peeper who searches the very bosoms which we hide” and says that “she’d rather not have him inspect her quite so close”. Gismondo, however, is unimpressed, telling her that “though you hide yourselves from other men as much as you will and can, my fair ladies, you neither can nor ought to hide yourselves from lovers”.

One of the best examples of the voyeuristic male gaze can be found in Matteo Bandello’s collection of short stories called Novelle (1506-1555), which contains numerous descriptions of beautiful young women, descending from their curls of “clear and lucent gold” to their mouths “engraved with the finest rubies” and their breasts of “white and polished alabaster”. In one of Bandello’s stories, a rejected admirer takes revenge on his beloved, a married lady called Eleonora. The young man, Pompeo, first forces her to have sex with him, and later exposes her naked body to a group of gentlemen that he invites into the bedroom. Taking care not to expose Eleonora’s face, he slowly withdrew the thin sheet that covered her:

Pompeo, then, raising a little of the sheet, uncovered two snow white feet, small and long, with toes like sheer ivory, slender and long, and nails that seemed like pearl. Nor did he stop there, but delayed not until he had unveiled almost all the thighs, at the sight of which the onlookers felt something awaken that had slept (…) Hiding with a part of the sheet that which lies between the thighs, he uncovered the breast to the throat, which was a marvelous joy for the beholders to see, for that, although the whole body was most beautifully fashioned, the breast was wonderful past all belief. They all with incredible delight beheld the well-elevated and snow-white bosom, with its two firm round breasts, that seemed molded of alabaster, save that, for the lady’s trembling, there was visible a certain fluttering which was marvelously pleasing to the eye.

Scene from the Orlando Furioso in which the knight Ruggiero rescues “damsel-in-distress” Angelica. Painting by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1819). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

“A pair of apples, not yet ripe”

Although Renaissance writers much rather let the private parts of women remain private (as they are “secrets which Nature evidently made a point of hiding”), they display a particular interest for female breasts. Ludovico Ariosto’s descriptions are both vivid and poetic:

The small rounded breasts were like beads of milk newly pressed from a reed. They were so set apart, they resembled two little hillocks and between them a pleasant shady dell in the season when winter snow still lies in the hollows.

Like those of Olympia above, the breasts of female characters are always round, firm and well parted from one another. They are often compared to a pair of apples, and are, like the rest of their body, white like ivory or marble or alabaster, as if they were sculptures. Apart from the fact that these breasts all seem to be inspired by classical marble statues, there is one other thing that stands out: their size. The breasts of these women are always “somewhat elevated” and small like “unripe apples”. At times, the small size of the breasts is connected to the age of these women. Take for instance Bembo’s earlier description of Sabinetta’s breasts, or Bandello’s description of “Ginevra la bionda”, whose virginal breast was “not much raised, but modestly showed its charms such as sorted with the damsel’s tender age”. In Renaissance Italy, girls were seen as appropriate objects of desire at a far earlier age than in our own modern day, as the marriage age was much lower. Girls from the upper classes usually married in their mid- to late-teens, while their husband was often in his late twenties, or much older (Pietro Bembo met his Faustina when he was 43 and she was only 16).

The preference for small breasts in Renaissance Italy not only had to do with the ideal age of marriageable women, but also with their sexual identity. Historian Kim Phillips wrote an article in which she argued that late medieval people were convinced that large breasts were a sign of sexual experience, whereas small breasts were a sign of modesty or virginity. She mentions a number of medical treatises that include recipes for women to suppress the growth of their breast or reduce their size through specific mixtures of herbs and other natural products. To live up to the beauty standards of the time, and not to get a bad reputation as immodest or indecent, women could even wear a predecessor of the modern bra to flatten their chests. I have come across similar recipes in medical treatises from Renaissance Italy. Pietro Bairo’s Secreti Medicinali includes a chapter entitled “Of those things that forbid the breasts from growing, and that straighten them when they hang down uglily." His treatments consist of compresses and sponge baths made with ingredients such as hemlock, vinegar and the sap of an oak tree.

Somewhere along the road to Hooters and the Push-Up-Bra, Western aesthetics of female breasts have witnessed a tremendous change.

15th century linen “bra” found at Lengberg Castle, East-Tyrol. Photo: Institute for Archaeology, University of Innsbruck.

References and further reading:

Kim M. Phillips, ‘The Breasts of Virgins: Sexual Reputation and Young Women’s Bodies in Medieval Culture and Society’, Cultural and Social History 15 (2018).

Kim M. Phillips, Medieval Breasts: A Petite History (Forthcoming).

© Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

*This article has been updated on 03/07/2020