A sculptural puzzle: The demolished church of Kerkdriel

The virtual 3D-reconstruction of a church’s building history is all the fashion in architectural history. But how does the study of architectural sculpture fit in? Can 3D-modelling be a tool to help locate architecture that is no longer in context?

Reconstructing churches

On 20 October 2017, I attended a conference on the (virtual) reconstruction of buildings in the town hall of ’s-Hertogenbosch. Virtual techniques are increasingly becoming an important tool in testing the feasibility of theories and thoughts concerning the reconstruction of medieval monuments and are considered instrumental in gaining more precise insights in the actual building processes. Having studied the Kerkdriel sculpture extensively at the request of the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed (Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands), I was asked to discuss the architectural sculpture of the demolished church of Kerkdriel in relation to that of the far grander church of St John in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. How does such a topic fit in with 3D-reconstruction?

A victim of war and religious conflict

Kerkdriel is situated along the river Meuse, some 12 kilometres to the north of ’s-Hertogenbosch. It was one of the southernmost places in the diocese of Utrecht, belonging to the chapter of St Saviour or Oudmunster, another lost church, once situated to the south of the cathedral of Utrecht. On 23 April 1945, the retreating German army blew up the Kerkdriel church tower. During its collapse, it took down the western part of the nave. The eastern part survived the onslaught, but the vault over the crossing collapsed and the vaults of the transept arms sustained considerable damage, as did the roofs of the transepts and choir. The Protestant community in Kerkdriel, that owned the church, was too small to be able to finance a full restoration. The much larger Catholic community, that had also lost its church, was willing to rebuild the entire edifice on the condition that it be returned to them. They were in fact so eager that they even offered to build a new protestant church on another location. But it all came to nothing and in 1952 the old church was replaced by a rather basic new protestant church.

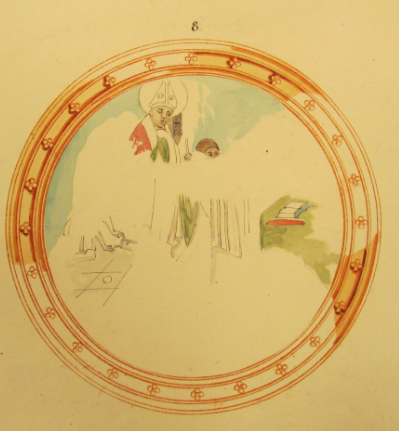

With the demolition of the badly-damaged church of Kerkdriel one of the Netherlands’ most sumptuously decorated parish churches was lost forever. The building had been renowned for its wonderful sixteenth-century paintings on the choir vaults and, to a lesser extent, for its extensive sculptural decor that included a series of prophets, wise and foolish virgins, various heads and a large number of foliage carvings. The paintings live on in a series of nineteenth-century watercolours and some rather poor photographs. The sculpture fared better and is now a part of the collection of architectural fragments held by the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed.

A sculptural puzzle

Unfortunately, no record of the exact provenance of the sculptures exists, and so in order to find out where precisely each sculpture came from, I had to rely on photographs, descriptions, accounts, plans and drawings. This enabled me to reconstruct the sculptural decor of the nave, crossing and transept. However, the decoration of the western extensions of the aisles flanking the tower and of the interior of the choir remained blind spots. Of the aisle terminations there are only two blurred photographs. The reason why there is so little documentation of the choir is that the small protestant community of Kerkdriel did not require the entire medieval church for its services and used only the nave. A wall separated the nave from the choir and transept and the windows in the choir were bricked up, making it a dark and inaccessible place, used only for storage.

Of all the remaining sculptures, the original location of two very fine corbels proved a particularly hard nut to crack. Both are slightly smaller than the sculptures from the nave and transept, and of a somewhat different construction and style. One represents the half-figure of a bearded balding man holding a book and a broken-off sword, who can be identified as St Paul. The other shows the half-figure of an angel who used to carry a musical instrument. Judging from their style and the characteristic S-shaped hair and forked beard of St Paul, the corbels date to around 1360-1370. The closest parallel for them is to be found in the former sacristy of the church of St John in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, built against the south wall of the southern transept. Although this sacristy dates to the middle of the fifteenth century, the sculpture is earlier, dating to around 1360-1370. Apparently, it was reused from the predecessor building, as is evident from the adaptations that were necessary to fit it into its present position. The stylistic parallels between the Kerkdriel and ‘s-Hertogenbosch sculptures are so close as to suggest they were made in the same workshop, i.e. in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. The 1360-1370 date of the two Kerkdriel corbels suggests a provenance from the fourteenth-century choir. A provenance from the sixteenth-century aisle terminations is only possible if we are dealing with second-hand material derived from the church of St John in ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

A provenance from the choir?

The choir of the Kerkdriel church had two rectangular cross-vaulted bays and a five-sided termination and – as has been noted –is dated to the fourteenth century. The architectural sculpture could have provided a more precise date but unfortunately there is no sculpture that can, with any degree of certainty, be attributed to this part of the building. However, sections and plans of the church show that there was room for ten capitals, four corbels and three keystones or bosses. A 1930 description of the church mentions corbels decorated with heads in the choir. An 1952 overview of the sculptures to be salvaged lists five large and three small corbels from the choir, without giving further specifics. A measured section of the church made in 1932 suggests that there was a series of four large corbels on top of the 2 metre high plinth of the five-sided choir apse. These records indicate that the choir was well-provided with sculptural decoration.

An argument against placing the corbels of St Paul and the angel in the choir is that they are shown lying about on a series of photographs taken during the 1949-1950 archaeological excavations carried out inside the church ruins. When these photographs were taken, the choir was still standing and as there were plans for rebuilding, the sculpture mentioned on the 1952 list is likely to have still been in place, which would seem to imply that the two corbels did not come from the choir. However, the only other place where they could be accommodated is in the sixteenth-century extensions of the nave aisles. Such a location seems unlikely in view of the fourteenth-century date of the sculptures and the fact they are not mentioned in descriptions of the church predating its demolition, the more so as they are among the finest sculptures of the church. Had they been situated here they would have been easily visible. The choir option therefore remains the only likely possibility. Maybe the two corbels were found during the excavations or were, for some unknown reason, removed from their architectural context prior to 1952.

But why would St Paul feature in the choir of a church dedicated to St Martin? This answer to this question is not difficult to find and, if correct, provides more evidence for a provenance from this location. There is in fact some slight evidence that St Paul was a co-patron of the church. Not only did the abbey of St Paul in Utrecht possess considerable rights and lands in Kerkdriel, the sixteenth-century paintings on the choir vault depicted two scenes with donors and their saints. In the first, St Martin was shown with a clerical person kneeling in front of a prayer-stool; in the second, a figure who very much resembles St Paul accompanied three ecclesiastics. This suggests the Kerkdriel choir could well have housed the corbels with the angel and St Paul, and I would like to think they were accompanied there by the figures of St Martin and a second angel, to make a satisfactory ensemble.

To my mind, this exercise shows that an in-depth study of the material can produce rather valuable data for reconstruction. Even though 3D-visualisation is not going to help locate sculptures to their one-time locations, this type of research is essential to provide input data and to make 3D-visualisations more detailed and reliable.

© Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.