A World in the Back of a Book

Why was a medieval note on the world's regions added on a scrap of parchment at the end of a Roman geographic work (Leiden UB, BPL 68)? From India to Ireland, Cappadocia to cannibals, the note's mixture of fact and fiction showcases a reader's interest in the bounds of their known world.

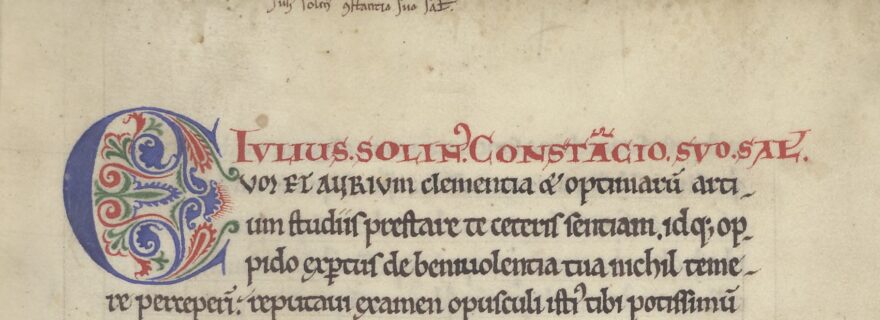

Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheken (UBL), BPL 68 contains a copy of Gaius Julius Solinus’s Collectanea rerum memorabilium (Collection of Marvellous Things), a work written in the third century which described the extents of the Roman empire, its wonders and marvels. Combining fact and fiction, Solinus’s blend of geography and mythology had lasting appeal, particularly in shaping the tradition of the medieval bestiary (collections of moralising stories about animals and mythological beasts) and was frequently found in monastic libraries. The work was phenomenally popular, surviving in over 200 medieval manuscripts. The copy found in Leiden UB, BPL 68 dates from the second half of the twelfth century and is written in a proto-Gothic bookhand. It is a monastic production; Reading Abbey in England has been suggested as a possible place of origin on the basis of the manuscript's decoration and ruling pattern.

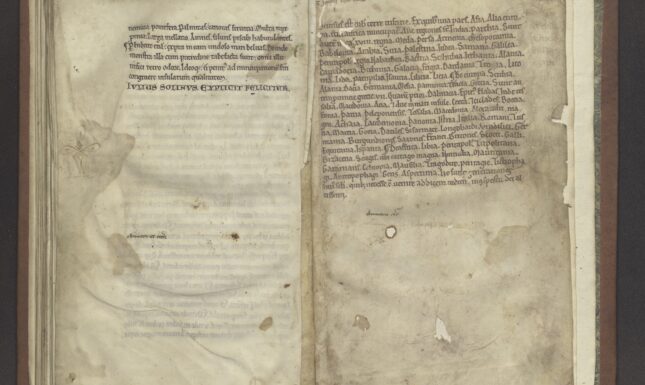

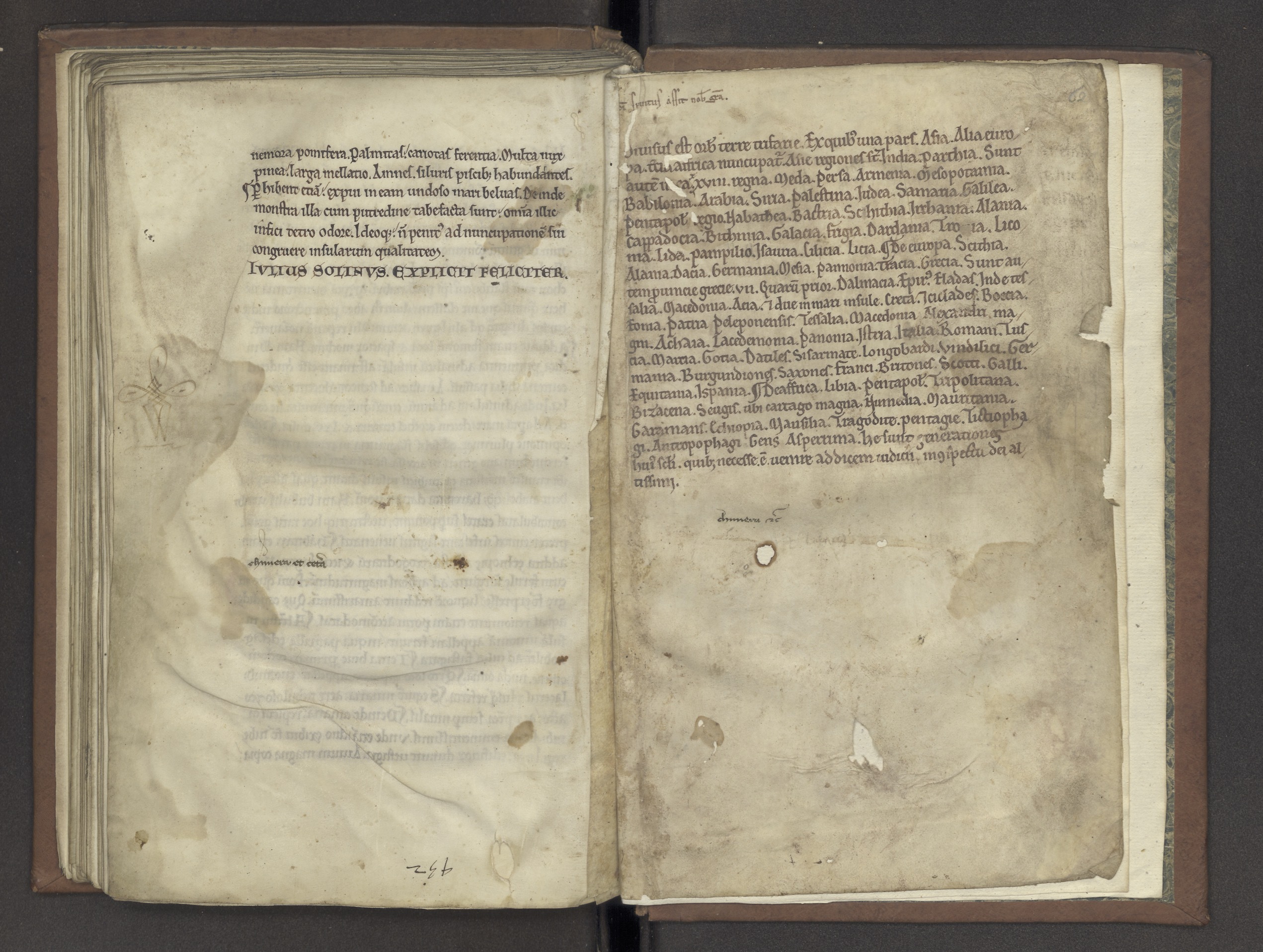

This post concerns not Solinus’s text itself, but a note added at the conclusion of the manuscript which expands on the Roman writer’s geographic themes. I came across this note while preparing teaching materials for the medieval manuscript courses I teach at Leiden University. The note (f. 62r) occupies about half a page and is written on an inserted parchment leaf (slightly smaller than the pages carrying Solinus’s text). Its twenty lines are copied in brownish ink and plainly executed; the majuscule letters throughout are carefully formed and two paraph signs (¶) are placed to break up the text in lines 7 and 15. The leaf was pre-ruled, closely anticipating the length of the passage (in fact, over-estimating it by two lines). Given the similarities in theme and style, it is clear that the note was a near-contemporary addition to the manuscript, meaning that it can potentially inform us about the broader interests of Solinus’s medieval readers. Above the note, another hand, writing with a thin nib, has added the words 'S(an)c(t)i spiritus assit nob(is) gr(ati)a' ('May the grace of the Holy Spirit be with us'). This hand is identical to that which re-copied the opening rubric in the upper margin of f. 1r (see detail at top of header image), demonstrating that this leaf was bound with the Solinus volume from an early date.

‘Diuisus est orb(is) terre trifarie’

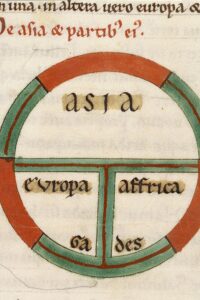

The note opens with the words: ‘The globe of the world is divided in three [parts], one part of which is called Asia, the other Europe, the third Africa’. This tripartite division of the world reflects biblical and Christian geographic traditions. After the Flood, according to Genesis 9.18-19, Noah’s three sons - Shem, Ham, and Japheth - became the progenitors of ‘the people who were scattered over the whole earth.’ Elaborated in later accounts, such as Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities (93 CE), a tradition developed that each of Noah’s sons had been allocated a portion of land. This tripartite division was the basis of the frequent medieval diagrammatic presentation of the world in the form of the so-called T-O map. This depicted the world (O) as sliced into three segments, spliced by the three water bodies (T) of the Mediterranean, Nile and Don. This note has a comparable tripartite structure; the first section describes the regions of Asia, followed by those of Europe and Africa in turn.

The note reprises information found in the widely-circulated sixth-century encyclopaedia, the Etymologiae (‘Etymologies’) of Isidore of Seville. The note's content was probably not derived directly from this work, but from an intermediary such as an epitome or extract collection. However, the parallels between it and Isidore's work are notable. Utilising similar wording, Isidore also opened his account of the regions of the world in Book XIV (‘On the earth and its parts’) with reference to its tripartite division (Etymologiae XIV.ii.1). Moreover, the ordering of the regions of Asia (lines 2-7) provided in this note mirror the narrative order offered by Isidore. Here, as in the Etymologiae, India and Parthia are the first regions listed (cf. Etymologiae XIV.iii.5-8), followed by reference to its eighteen kingdoms (cf. Etymologiae XIV.iii.9). The note then lists the following regions:

Media, Persia, Armenia, Mesopotamia, Babylon, Arabia, Syria, Palestine, Judea, Samaria, Galilee, Pentapolis, the region Nabathea, Bactria, Scythia, Hyrcania. Albania, Cappadocia, Bithynia, Galatia, Phrygia, Dardania, Troy, Lyconia, Lydia, Pamphylia, Isuaria, Cilicia, Lycia. (lines 3-7; cf. Etymologiae XIV.iii.10-44)

‘De europa’

Following the regions of Asia, the note turns to describe those of Europe. Again, the order of the account closely follows that of Isidore.

Of Europe. Scythia, Alania, Dacia, Germania, Moesia, Pannonia, Tracia, Greece. There are seven Greek provinces. The first Dalmatia, [then] Epirus, Hellas. Then Thessalia, Macedonia, Achea, and two islands in the sea, Crete and the Cyclades. Boeotia, Aeonia, the Peloponnesian fatherland, Thessaly, Macedonia of Alexander the Great, Achaia, Lacedaemonia, Pannonia, Istria. (lines 7-12; cf. Etymologiae XIV.iv.1-17)

The note then takes an intriguing turn, interspersing the names of various groups of peoples who lived across Europe among the geographic regions:

Italy, the Romans, Tuscany, Marsia, the land of the Goths, Dacians [?], Sarmatians, Lombards, Vindelici, Germania, Burgundians, Saxons, Franks, Britons, the Irish, Gauls, Aquitania, Hispania. (lines 12-15)

Again, Isidore’s Etymologiae is a likely ultimate source of these groupings, in this case Book IX.ii.84-104 (‘Languages, nations, reigns…’). Mixing geography and ethnography, peppered with uncontextualized historical knowledge, this information allowed the note’s likely English reader to populate mentally the distant lands lying to the east and south of their monastery.

‘De affrica’

A similar hotchpotch of geographic and ethnographic knowledge is found in the note’s description of Africa. First, the note describes its regions, again following the order of Etymologiae, Book XIV.v.1-14:

Of Africa. Libya, Pentapolis, Tripolis, Byzacium. Zeugis - where Great Carthage is, Numidia, Mauretania, Garama, Ethiopia, Massylia. (lines 15-17)

The note continues with four groups of peoples:

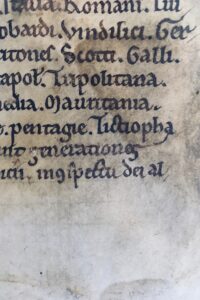

Trochodites, Pentagie, Tictiophagi, Anthropophagians. (lines 17-18)

‘Trochodites’ were, according to Isidore, ‘a tribe of Ethiopians so called because they run with such speed that they chase down wild animals on foot’ (trans. Barney et al., p. 199). ‘Tictiophagi’ is a corruption of ‘Icthyophagi’, ‘fish-eaters’, referring to a group of people who lived off fish alone; likewise, ‘Pentagi’ would seem to be a corruption of Isidore’s ‘Pamphagi’, a people who chew on anything available. Finally, the Anthropophagians, a ‘fierce race’ [gens asperrima], were cannibals, conflating the limits of the uncivilised human condition with the limits of the medieval reader’s known geographic world (cf. Etymologiae

Book IX.ii.128-132).

The list concludes with the portentous words:

These are the generations of this age for whom it is necessary to come into the presence of God the Almighty on the Day of Judgement. (lines 18-19)

As these final words suggest, this note is underpinned by a Christianised geographic worldview. The note's contents implicitly invited the medieval reader to contrast its perspective with the Roman, pagan, account of Solinus contained in the rest of the codex.

Christianising the world

There is evidence that at least one (monastic) reader studied the note carefully. The ‘Asian’ section of the note seems to have attracted particular attention, probably because it contained references to areas mentioned regularly in the Bible. A tentative interlinear addition of a ‘x’ to the Roman numeral ‘xviii’ in the account of the regions of Asia suggests that one annotator attempted (incorrectly) to reconcile the note’s mention of eighteen kingdoms with the number of regions actually mentioned (which add up to twenty-nine). Another seems to have noticed that this part of the list was incomplete, and added some further words with a stylus (in drypoint) in the margin - now visible as shadowy grey tracings. Not all terms are presently legible, but the (second and fourth) words, Fenicia (‘Phoenicia’) and Egipte

(‘Egypt’) can be made out.

The note's Christianised worldview is also made explicit in its final line. On the one hand its invocation reminds the reader of the equality of all when faced with the judgement of an (uncompromising?) God. On the other hand, it could also be read as a challenge. As Geraldine Heng’s thoughtful appraisal of the theoretic loading of cannibalism in medieval accounts notes, this practice was particularly vilified by medieval Christian scholars. While Christians effectively promoted a ‘sacred cannibalism’ in the eating of the Eucharist, the practice was descriptively employed as an ‘instrumentally useful... definition’ to underscore ‘malignant otherness’ (Heng, pp. 26, 28-9). Here the association of cannibals and other ‘fierce peoples’ with a geographic and mentally distant ‘Africa’ illustrates the intolerances of the Middle Ages, particularly with regard to race.

Future directions and teaching applications

The sources and content of this note deserve further analysis. As previously mentioned, I came across this note while preparing object-based teaching for the medieval manuscript courses I will offer in the upcoming academic year. In spite of its brevity, this note offers a good point of departure for a variety of avenues of discussion with students. From the perspective of a teacher working with special collections materials, it shows how medieval readers physically and textually expanded their manuscripts to include extra relevant information. Further, the physical expansion of the book parallels an intellectual expansion of its content; it hints at a reader’s struggle to accommodate ‘pagan’ sources, such as Solinus, within a Christianised curriculum. Finally, this short source could be used to discuss aspects of medieval geographical knowledge, medieval identities and race, along with facilitating critique of the limits (literal and mental) of the medieval worldview.

Transcription of geographic note: BPL 68, f. 62r

Diuisus est orb(is) terre trifarie. Ex quib(us) una pars. Asia. Alia europa. t(er)cia affrica nuncupat(ur). Asie regiones s(un)t India. Parthia. Sunt aute[m] i[[n]] ea \x/xviii regna. Meda. Persa. Armenia. Mesopotamia. Babilonia. Arabia. Siria. Palestina. Iudea. Samaria. Galilea. Pentapol(is). regio Nabathea. Bactria. Schithia. Irchania. Alania. Cappadocia. Bithinia. Galacia. Frigia. Dardania. Troia. Liconia. Lida. Pampilio. Isauria. Cilica. Licia. ¶ De europa. Scithia. Alania. Dacia. Germania. Mesia. Pannonia. Tracia. Grecia. Sunt autem p(ro)vincie grecie .vii. Quaru(m) prior. Dalmacia. Epir(us). Eladas. Inde tersalia. Macedonia. Acia. (et) due in mari insule. Creta (et) ciclades. Boecia. Eonia. Patria Peleponensis. Tessalia. Macedonia Alexandri magni. Achaia. Lacedemonia. Panonia. Istria. Italia. Romani. Tuscia. Marcia. Gotia. Datiles. Sisarmate. Longobardi. Vindilici. Germania. Burgundiones. Saxones. Franci. Britones. Scotti. Galli. Equitania. Ispania. ¶ De affrica. Libia. Pentapol(is). Tripolitana. Bizacena. Seugis. ubi cartago magna. Numedia. Mauritania. Garamans. Echiopia. Mausilia. Tragodite. pentagie. Tictiophagi. Antrophophagi. Gens Asperrima. He sunt generationes hui(us) s(ae)c(u)li quib(us) necesse e(st) uenire ad dicem [sic] iudicii in (con)spectu dei altissimi.

* Editorial note: Spelling and punctuation have not been regularised; abbreviations are expanded within rounded brackets; line breaks have not been preserved.

Further reading:

Primary sources:

Leiden UB, BPL 68: Solinus, Collectanea rerum memorabilium and geographic note.

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 016II: Matthew Paris, Chronica Major.

Isidore of Seville, Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi Etymologiarum Sive Originvm Libri XX, ed. W. M. Lindsay (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1911).

Isidore of Seville, The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans. Stephen A. Barney et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Secondary sources:

Coates, A., English Medieval Books: The Reading Abbey Collections from Foundation to Dispersal (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999).

Dover, P., 'Reading "Pliny's ape" in the Renaissance: The Polyhistor of Caius Julius Solinus in the first century of print', in J. König, G. Woolf (eds) Encyclopaedism from Antiquity to the Renaissance. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2013), pp. 414-443.

Heng, G., Empire of Magic: Medieval Romance and the Politics of Cultural Fantasy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003).

Watson, K. L., Insatiable Appetites: Imperial Encounters with Cannibals in the North Atlantic World (New York: NYU Press, 2015).

Wood, J. and Fear, A. (eds), Isidore of Seville and his Reception in The Early Middle Ages. Transmitting and Transforming Knowledge (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016).

Woodward, D., 'Reality, Symbolism, Time and Space in Medieval World Maps', Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 75 (1985), 510-521.

Woodward, D., 'Medieval Mappaemundi', in J. B. Harley and D. Woodward (eds), The History of Cartography, vol. 1: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1987), pp. 286-370.

© Irene O'Daly and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2024. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Irene O'Daly and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.