"Alber, I beseech thee": Healing magic from the grave

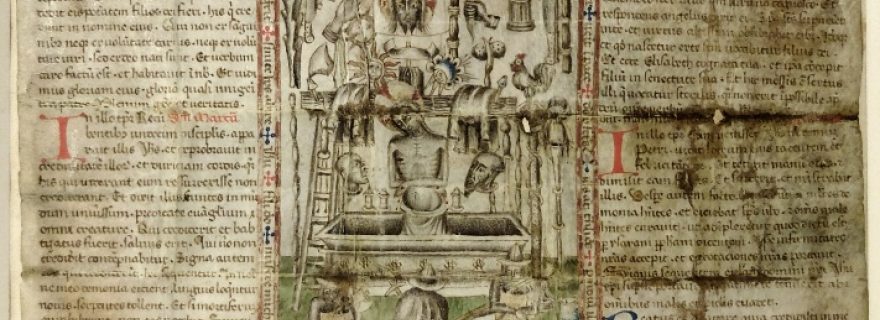

Medieval textual amulets, made out of metal or parchment, were worn around the neck to ward off evil powers.

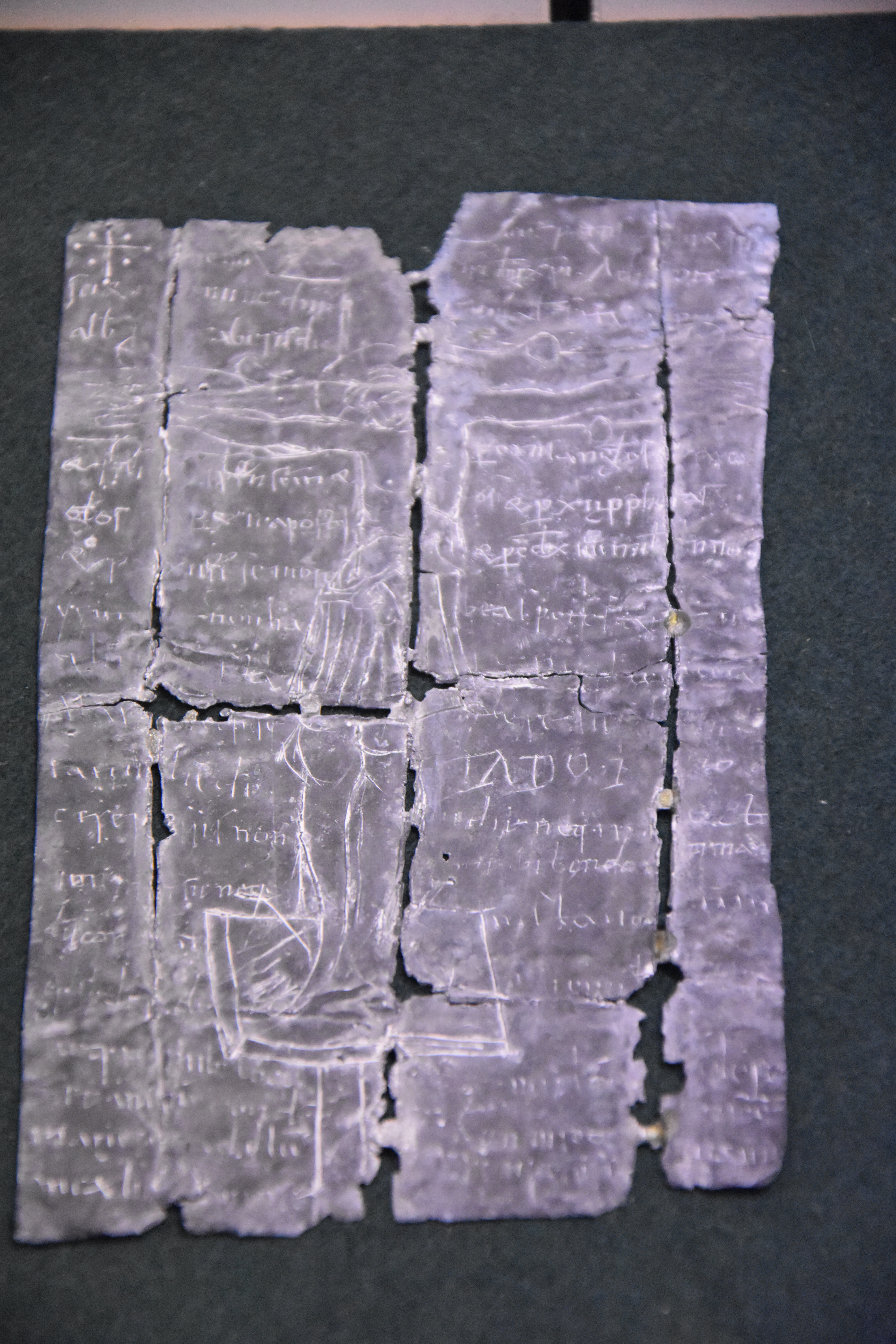

During a visit to Halberstadt in the fall of 2017 I came across a rather unusual textual amulet in the Historisches Museum, found during archaeological excavations in 1983. It is decorated with a scratched-in crucifix and bears an extensive text conjuring up the names of the Trinity, Christ, all the angels, apostles and prophets, the 24 Elders and 264.000 Innocents in order to chase away the Alber, a fairy-tale version of Satan or the devil, and stop harming a little boy called Tado. Wondering how common the use of such lead textual amulets was and from what type of danger they protected the persons carrying them, I decided to do a little research.

Little Tado’s grave and amulet

In 1142, a boy named Tado died at the age of eight and was laid to rest in the cemetery south of Our Lady’s Church in Halberstadt. Round his neck was a cord with a tiny textile bag suspended from it. The actual bag had perished, but left a textile imprint on the amulet it contained. This amulet was made from a lead sheet, measuring 85 x 138 mm, that had been folded many times over and stamped repeatedly so as to make it into a neat little parcel of 27 x 43 mm. The folding and stamping of the lead accounts for the illegibility and disappearance of a great deal of the eighteen lines of Latin text covering its surface, on either side of a large scratched-in crucifix, showing a dead and unbearded Christ. In English the inscription reads:

In the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy (line 1) Ghost, in the name of Our Lord Jesus Christ. I beseech thee (line 2) Alber, who art also known as the Devil and Satan, by the Father (line 3) and the Son and the Holy Ghost and by all the Angels and Arch (line 4) angels, by the 12 Apostles and by the 12 Prophets (line 5) and by the 24 Elders and by the 264.000 Inno (line 6) cents: Thou shalt not have power (line 7) […](lines 8 and 9 are gone) God’s friend Tado. So that you cannot do harm (line 10) not by day and not by night (line 11), not in […] not while drinking nor while eat (line 12) ing […] (line 13 and 14 are gone) nor […] place (line 15) and shall not damn the soul […] (line 16) [...] and cannot […] in the year (line 17) 1142 of the Lord (line 18).

In addition, a small scratchy drawing of a cross appears in the upper left hand corner.

A rare sort of amulet?

Tado’s lead textual amulet was a rare find, but since its discovery several more examples have come to light, which were discussed in a small but informative booklet by Arnold Muhl and Mirko Gutjahr, published in 2013. Apparently, the finding of the Halberstadt amulet created an awareness of the existence of this type of object and as a consequence more have been found, dating from the eleventh century to the late Middle Ages, and their number is still on the increase. In addition, there are examples from England and the Scandinavian countries. Southern Europe has also yielded quite a number of textual amulets, but these tend to be much older than their northern-European counterparts, dating as they do between the fourth and the eighth centuries. It is clear, however, that the usage of lead textual amulets was once more widespread than is apparent from the physical evidence surviving today. Our Dutch soil has unfortunately yielded no examples yet, at least not that I am aware of. There is however some documentary evidence attesting to the use of textual amulets here, even though it is late in date and not exactly abounding. They are mentioned only in connection with the healing of haemophilic and epileptic patients. But, who knows, there may be examples out there waiting for discovery.

Lead was apparently a good choice for a talisman as it was believed to have protective and healing qualities. Already in the eighth-century Einsiedeln Codex, parchment, lead, copper and iron are named as suitable materials for the manufacturing of written incantations. This having been said, the amulet’s main working ingredients were, of course, the word of God and the image of Christ, which were believed to have mighty powers. Second came the prophets, apostles, elders and innocents. These were all conjured up to help Addo’s body and/or soul against the ‘Alber’, a demon or Satan. The Alber was a figure from Germanic mythology, an ‘Alb’, ‘Elb’ or Elf, a creature that initially was not necessarily bad. In Christian thought, however, it was linked to Satan, and the ‘Alber’ came to be seen as the cause of various forms of sickness. An amulet from Schleswig, dating to the eleventh century and found in 1976, protected its bearer against ‘daemons sive albes’ by invoking the name of God in quoting the beginning of St John’s Gospel: ‘In principio erat verbum’. A lead amulet from Romdrup in Denmark adjures the ‘elf-men or elf-women and demons through the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, that you do not hurt this servant of God, Nicholas, neither on the eyes nor on the head nor on the limbs’.

Other textual amulets mention demons, Satan and such like, rather than the Alber. An amulet from Klein-Dreileben, dated between the 12th and 14th centuries and found near a former churchyard, was meant to protect its bearer Merherd from attacks by Satan by invoking God the father. An 11th- or 12th-century specimen from Salhausen near Wolmirstadt was found near the left shoulder of a deceased child, banishing ‘many-coloured female demons’. An amulet from the deserted village of Seelschen near Ummendorf addresses the demons and children of the devil. It dates to 1160 and was intended to protect a person named Hazziga.

On the making and function of the textual amulet

The Schleswig amulet conjured the ‘demons and elves, all the infections of all illnesses, and all obstructions not to harm the servant of God by night or by day, nor at any hour’. Threatening them with the cross of Christ, the charm told these enemy powers to be gone. Other amulets also served as healing charms, for example a runic specimen from Bergen that reads: ‘In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Cure! May God’s five wounds be medicine. May my medicine be the Holy Cross and Christs passion. He who moulded and washed me with holy blood, expelled the fever which strove to torment me’.

An 11th-century manuscript from the Rhenish abbey of Maria Laach (University Library Bonn, cod. membr. 218 (66a), fol. 82v)., describes how one should go about making an effective amulet: ‘In the name of the Lord take lead and make a cross in it and write thereon before the rest “See the cross of God” and at the end “Peace be with thee, Halleluja” And bind this on the neck of the person stricken with illness’. By the fifteenth century, the procedure had become more elaborate (Cambridge, Trinity College, MS. R. 14. 51, fol. 30r):

Take a sheet of lead and make it square and place a cross in every corner in this way [a picture is inserted here] And when you make the first cross and draw it, say to yourself a paternoster and an Ave Maria, until you come to the passage concerning the daily bread. And when you are making the next cross you will repeat the paternoster and Ave Maria with good intent and so you proceed until you have made all five crosses. And then you will pray five paternosters and five Ave Maria’s. And to these prayers you will say: these five wounds of God are a medicine to me, as the merciful cross and the suffering of Christ may be remedies unto me.

A fifteenth-century manuscript from Heidelberg recommends hanging a lead amulet with lettering from the neck of people struck by epilepsy to effect a cure.

In view of the above, it seems entirely possible that Tado was given his amulet to ward off a deadly illness, the more so as the medicinal use of such objects is attested to in various written sources. Unfortunately for Tado and his parents, the amulet failed to protect him.

Short bibliography:

Willy L. Braekman, Middeleeuwse witte en zwarte magie in het Nederlands taalgebied, 1997.

Mindy MacLeod and Bernard Mees, Runic Amulets and Magic Obects, Woodbridge 2006.

Arnold Muhl and Mirko Gutjahr, Magische Beschwörungen in Blei. Inschriftentäfelchen des Mittelalters aus Sachsen-Anhalt, Kleine Hefte zur Archäologie in Sachsen-Anhalt 10, 2013.

Don C. Skemer, Binding Words. Textual Amulets in the Middle Ages, Pennsylvania 2006.

© Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.