Before bones became waste: the biography of reused bone tools

Reuse was not an unusual phenomenon in the early Middle Ages. While it is more commonly known that precious materials such as marble and metal have been reused, easily available and mundane materials such as bone have also been reused.

Traditionally, the early medieval economic system is approached in terms of manufacture, distribution, use and disposal. This is a fairly linear approach to the economy. In recent years, a more holistic approach has emerged, taking into account that materials and finished objects can also be reused and recycled rather than being turned directly into waste after primary use (Bavuso et al. 2023; Duckworth/Wilson 2020). Ellen Swift defines reuse as “secondary use in some kind” and as such an object can be unmodified, repaired or modified before reuse (2020, 425). Reuse is to be expected in either high valued materials or in commonly used, versatile raw materials (Swift 2020, 428). Bone tools belong to the second group. Whether bone tools have been reused can be examined microscopically by looking at use wear traces. Use wear traces can be characterised based on polish, striations and edge-rounding and can be interpreted with the aid of experimental archaeology. Experiments provide more insight into the traces that are produced by specific materials and movements on a particular bone tool (e.g. Van Gijn 1990; Van Gijn 2007). Based on use wear traces, a part of the bone tool assemblage of early medieval Oegstgeest and Dorestad seem to have been reused (Kromotaroeno 2015; Kromotaroeno 2024; Kromotaroeno in prep.). The focus of this blog will be on several examples of reused bone tools and what we can learn from them about reuse in Merovingian Oegstgeest.

Hide working

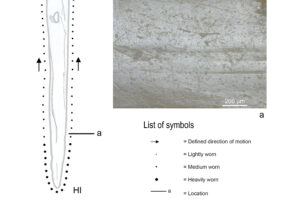

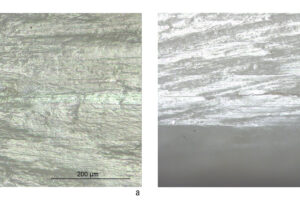

The first needle that showed traces of reuse was a worked pig fibula (number 392, see fig. 1a). The needle was worked with a knife. Several attempts were made to drill a perforation, after which it was finished with a twisting motion of a knife. The use wear traces on the needle consist of a very reflective polish and fine longitudinal striations (see fig.2a), similar to the traces found on an experimental bone needle that was stabbed through vegetable tanned hide for 60 minutes. Based on the rounded edge on top of the needle and the polish around the perforation, it is likely that the needle was used for sewing. Since the traces on the tip were more developed (see fig.2), the needle was probably both used for sewing vegetable tanned hide and for making holes in it. This needle could have been selected for the latter because of the oval cross-section of the point and its use for decorative purposes (Kromotaroeno 2015, 30-33, 67-71, 94).

Processing of wool and linen

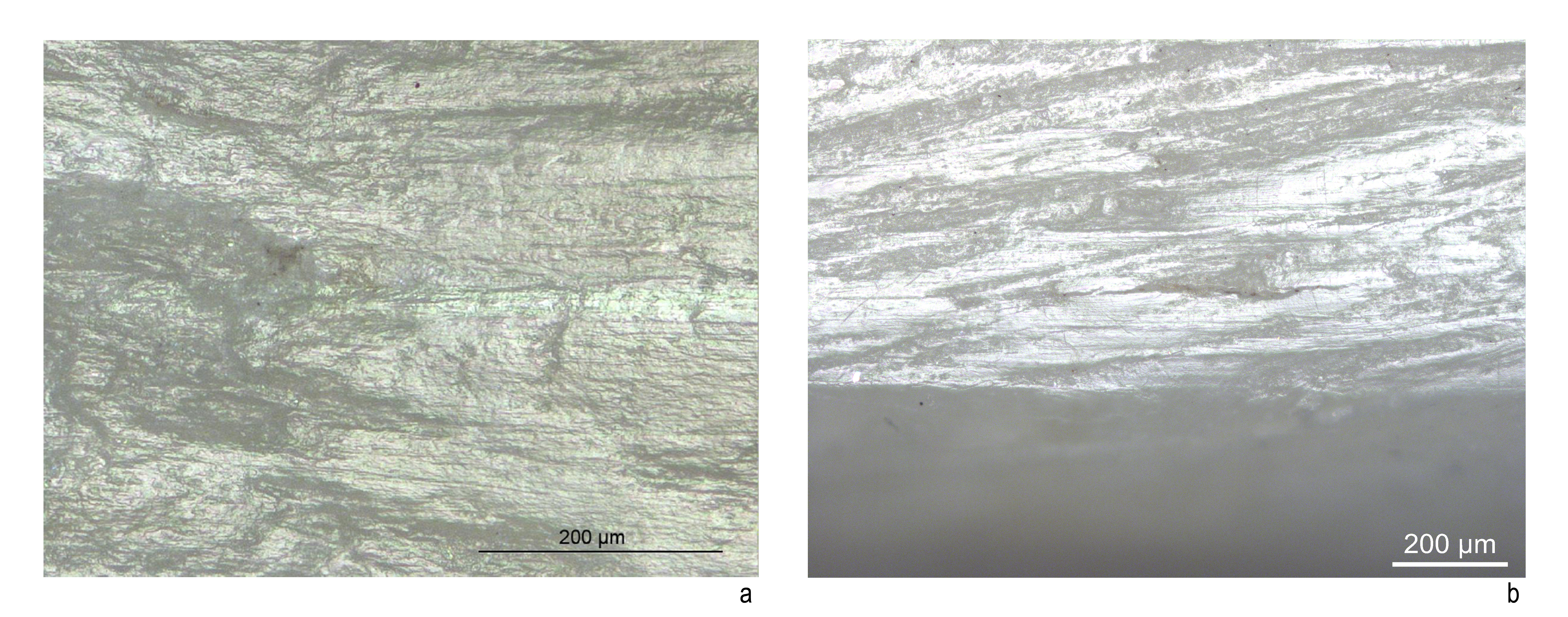

The second bone tool associated with reuse was a bone pin which was worked with a knife (number 1026, see fig.1b). It was completely covered with a microscopically visible polish. In some spots this polish was bright and greasy with a domed micro-topography. These traces resemble those on an experimental pin that was in contact with wool for a duration of 60 minutes (see fig.3a). Other spots were covered with a bright polish, a flat micro-topography and fine longitudinal striations (Kromotaroeno 2015, 27-30, 68, 75). This is typically seen in experiments with linen (see fig.3b).

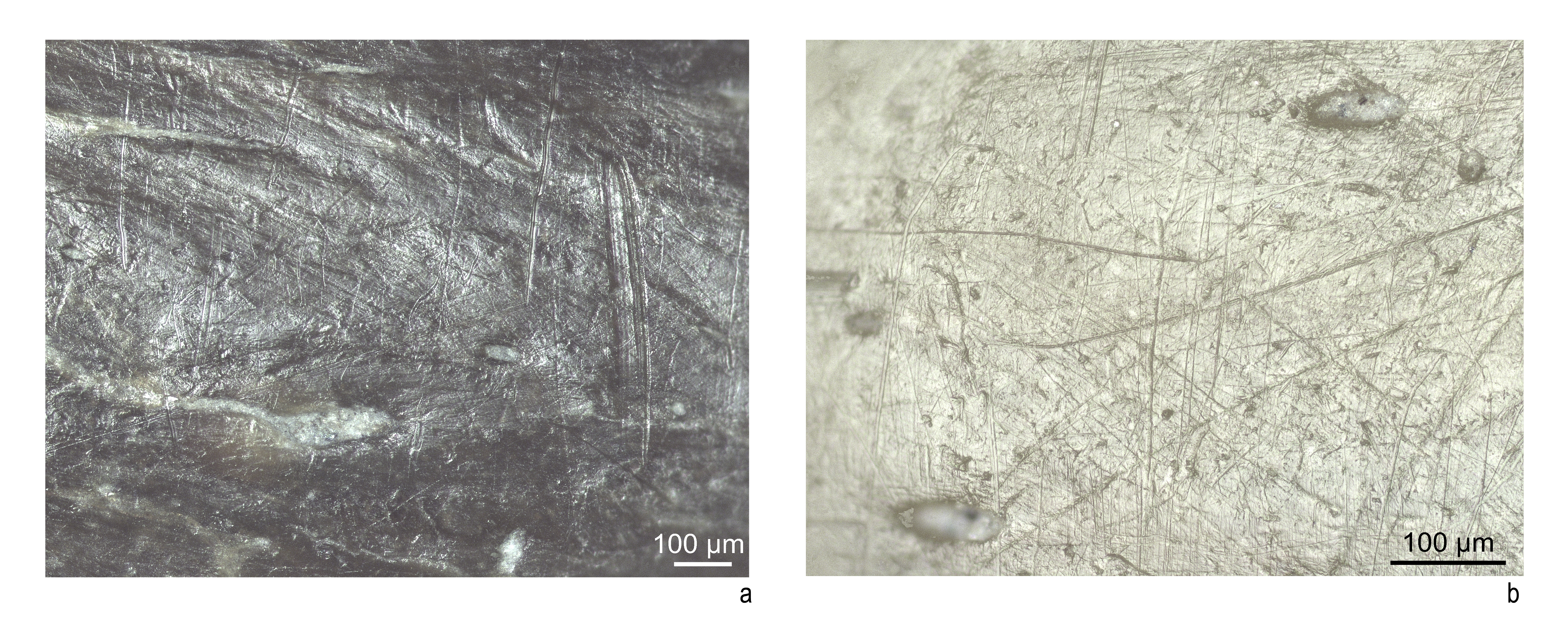

Another reused tool that came into contact with both wool and linen was a bone bipoint (number 55, see fig.1c). The bipoint was somewhat sloppily made with an irregular and asymmetrical shape. The manufacturing traces were absent. The middle part of the bipoint was oval in cross-section and was decorated with several crosses. One point was covered with typical traces of wool with a reflective, greasy polish and a domed micro-topography (see fig.4a). The traces gradually transformed into a flat micro-topography and a bright polish typical for linen. Traces were scarcely developed on the middle part of the bipoint. The other point of the bone tool was covered with randomly oriented striations (see fig.4b). These traces could not be associated with a specific contact material. The bipoint has probably been reused: one point was used on both linen and wool, the other point was used in an unknown activity with an unknown material. One tip was broken after use (Kromotaroeno 2015, 45-47).

Reuse in Oegstgeest

The above examples show that reuse in bone tools can be recognised by the presence of multiple working edges (number 55), a variation in the development of use wear traces (number 392) and traces associated with multiple contact materials and/or movements (number 55, 1026). Reused bone tools came into contact with hide or a combination of wool with linen (see also Kromotaroeno 2024). As far as could be determined, bone tools were not repaired or modified before reuse. It is therefore not always possible to recognise reused bone tools based on macroscopic examination alone.

Reuse seems to have occurred more often in Oegstgeest. Due to a shortage of wood, the wood in wells and buildings was reused (De Bruin 2022, 83). There was, however, no shortage of raw materials for the production of bone tools, given the huge number of bones found at the settlement (Llorente-Rodriguez et al. 2022, 348). As can be seen in the examples mentioned above, most bone tools were relatively easy to produce with a limited number of tools. Making bone needles and bipoints could have been part of the regular household activities (Kromotaroeno 2015, 111). Perhaps the practise of reuse stems from a rather opportunistic attitude towards bone tools (see also Van Gijn 2007, 88). Instead of producing new tools for every task, the inhabitants of Oegstgeest probably picked up useful tools that were already available. Future research will focus on reused bone tools from other early medieval settlements such as Dorestad. Ideally, the study of bone tools is combined with other artefact groups to better understand the processes behind reuse and recycling and their role in the early medieval economy.

References

Bavuso, I./G. Furlan/E.E. Intagliata/J. Steding, 2023: Circular Economy in the Roman Period and the Early Middle Ages – Methods of Analysis for a Future Agenda, Open Archaeology 2023 (https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2022-0301).

De Bruin, J./M. van Zon, 2021: The excavation, in J. De Bruin/C.C. Bakels/F.C.W.J. Theuws (eds.), 2021: Oegstgeest. A riverine settlement in the early medieval world system, Bonn (Merovingian archaeology in the Low Countries 7), 12- 83.

Duckworth, C.N./A. Wilson (eds.), 2020: Recycling and reuse in the Roman economy, Oxford.

Kromotaroeno, C.L.S., 2015: Osseous objects of Oegstgeest. A functional analysis of the bone and antler objects of the Early Medieval settlement of Oegstgeest (Nieuw-Rhijngeest Zuid), Leiden (unpublished Msc Thesis Leiden University).

Kromotaroeno, C.L.S., 2024: The story of needles and pins: what they tell us about Dorestad. An experimental journey – rewriting traces, poster presented at the 15th Meeting of the ICAZ Worked Bone Research Group Paris 2024, Leiden (https://www.wbrg.net/wp-conten...).

Llorente-Rodriguez, L./I.M.M. van der Jagt/K. Esser, 2021: Remarks on the faunal evidence at the Merovingian site of Oegstgeest (Zuid Holland), in J. De Bruin/ C.C. Bakels/ F.C.W.J. Theuws (eds.), 2021: Oegstgeest. A riverine settlement in the early medieval world system, Bonn (Merovingian archaeology in the Low Countries 7), 348-359.

Swift, E., 2020: Reuse of Roman artefacts in late antiquity and the early medieval west. A case study from Britain of bracelets and belt fittings, in C.N. Duckworth/ A. Wilson (eds.), 2020: Recycling and reuse in the Roman economy, Oxford, 425-446.

Van Gijn, A.L., 1990: The wear and tear of flint. Principles of functional analysis applied to Dutch Neolithic assemblages, Leiden (Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 22).

Van Gijn, A.L., 2007: The use of bone and antler tools: two examples from the Late Mesolithic in the Dutch coastal zone, in C. Gates St-Pierre/ R.B. Walker (eds.), 2007: Bones as tools: current methods and interpretations in worked bone studies, Oxford (BAR International Series 1622), 79-90.