Cicero’s Life Reconsidered: Late Medieval and Early Humanistic Approaches

Details about Cicero’s life – well attested through many documents from antiquity – were almost forgotten during the Middle Ages. Substantial interest in his biography reemerged in the fourteenth century in the context of the North-Italian city-states (comuni).

There is no personality of Greek or Roman antiquity about whose life we have more first-hand information than Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BCE). What we know mostly stems from himself. His speeches and philosophical works contain autoreferential passages, but the most spectacular insights can be found in the 37 books of private correspondence that were collected and divulged posthumously. The letters contain a wealth of information about Cicero’s daily routines (including gossip shared at dinner parties), his thoughts about political friends and enemies, and his tactical manoeuvres during the turbulent last decades of the Roman Republic.

Cicero – a richly documented life, poorly read

Of all this detailed information, very few pieces were transmitted into the Middle Ages. Cicero’s letters were hardly read, whereas his speeches were studied mostly for their rhetorical brilliance, not in order to understand their precise historical context. His most important work was the rhetorical treatise De inventione that was used as a schoolbook, often combined with the late antique commentary by Marius Victorinus (ca. 290 – ca. 363 CE) or other medieval commentaries that were written in the eleventh, twelfth or thirteenth centuries. Cicero therefore was considered a teacher of rhetoric, and often this role was completely detached from his political career as a Roman senator and ex-consul.

A good impression of how fragmented the interest in and knowledge of Cicero’s life in the Middle Ages had become, can be gathered from the chapters dedicated to him in Vincent of Beauvais’ (ca. 1190–1264) Speculum historiale. This thirteenth-century encyclopaedia collects a huge amount of quotations from Cicero’s works. Compared to the wealth of these quotes, the biographical section is meagre. The only elements of his biography that are mentioned are his fight against the conspirator Catiline and his year in exile. Three further items are attributed to him in Vincent’s chapters, although they actually stem from a later tradition:

1) Cicero is said to have fought in the Gallic War with Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE) – a confusion with his brother Quintus;

2) He lived as a philosopher in search of God – a reaction to the Church fathers’ attempts to prove that Cicero’s philosophical writings also had value for Christians;

3) The curious information stemming from Jerome (ca. 348–420 BCE) that Cicero refused to remarry after the divorce from his wife Terentia, because a man cannot serve both wisdom and a woman. We know that the historical Cicero did remarry (unhappily) after his divorce.

Increased interest in the fourteenth century

Knowledge of Cicero’s life changed rapidly in the fourteenth century (see Mabboux 2022, 195–218). Very important for this was the discovery of the Ciceronian correspondence (the Letters to Atticus in 1345 and the Letters to Friends in 1392). The huge amount of copies made of these two collections in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries testifies to the interest which these ego-documents triggered. But it would be wrong to assume that the discovery was the only incentive for biographical interest in Cicero. A second reason for this was the political developments from the thirteenth century onwards. Cities became increasingly independent from religious institution and fostered their own intellectual culture (the rise of the first universities is a good example for that new secular self-consciousness). The development also made it possible for intellectuals without noble or very rich ancestors to embark on a public career (for example, as secretary). We see this best reflected in the Italian comuni of the late thirteenth century and the role of the intellectual in them.

Cicero was a good role model for this group. Through the widespread description of the Catilinarian conspiracy written by the Roman historian Sallust (86 – ca. 35 BCE), medieval readers knew that Cicero also did not have senators among his ancestors, but was the offspring of a Roman knight. Actually, he was the first of his family to make a political career in Rome (a so-called homo novus, “new man”) due to his excellent oratorical abilities and great intellectual capacities. In two short biographies of Cicero written at the beginning of the fourteenth century, we we see that this aspect of his successful career– his learnedness – was of particular interest. Around 1300, an anonymous author (perhaps from the context of the Paduan ‘proto-humanist’ Lovato Lovati) composed a short biography entitled Summary of the life, deeds, intellectual excellence, works and death of the very famous and illustrious Marcus Tullius Cicero. About thirty years later, Giovanni Colonna (ca. 1298 – ca. 1343), a historian at the papal court in Avignon, included Cicero in his collection On famous men, a work consisting of numerous brief biographies of important personalities from the past.

Both writers mention at the beginning of their accounts that Cicero’s career was built upon his wisdom (sapientia). In the anonymous Summary, for example, the social advancement that education promises is palpable: “[Cicero] was of low origin, and although he was the poorest boy in school, he overcame his father’s poverty and proved to be so talented that he acquired for himself what no other man from an ordinary family had achieved, namely, to learn the liberal arts among the children of the nobility.” [Tilliette 2004, 1064]. It is not surprising that details of Cicero’s life mattered more than in previous centuries; he was, after all, presented as a role model for the young intellectual elite of the Italian comuni. We see that both biographies try to gather information about Cicero’s life and to evaluate them in a richer way.

In the decade before the rediscovery of Cicero’s letters, however, this was a complicated matter. Both Colonna and the anonymous biographer mostly relied on well-known ancient and late antique authorities (Sallust, Seneca, Lactantius, Jerome, Macrobius, and a few others) and tried to bring together their scattered pieces of information – a difficult task. Errors and misunderstandings concerning Cicero’s life (like the ones found in Vincent of Beauvais) therefore remained common. In the Summary, for example, Cicero’s father is said to have been a blacksmith (in antiquity, this was said about the father of one of Cicero’s most admired predecessors, the Greek orator Demosthenes). In Colonna, we find the peculiar information that Cicero ran a school of rhetoric in Rome that was so successful that the school of his rival Sallust (the historian) had to close down. The anecdote, lacking historical basis, reflects the persistence of the medieval image of Cicero as a rhetorical authority.

End of the fourteenth century: Cicero as political hero

The discovery of the letters was a game-changer – not in the sense of a renewed interest in Cicero’s personality, but with regard to the amount of historical and personal details that became available. The result is visible in two early fifteenth-century biographies of Cicero by Leonardo Bruni and Sicco Polenton. They detail they provide, along with its factual correctness, are on a totally different level than the anonymous Summary or Colonna’s Life of Cicero. What had not changed so radically, however, was the idea of Cicero as an exemplary figure of the past, of a role model for intellectuals – who by then mostly adhered to the new humanistic movement. In the Republican city states of Northern Italy, like Florence or Siena, Cicero's rhetorical exemplarity was supplemented by his exemplary political virtue; as a defender of Rome's republic, he could be transformed into a symbol of republican ideology.

When in the 1380s the Florentines wanted to decorate a meeting room in their city hall, the Palazzo Vecchio, with frescoes of illustrious men from the past, the chancellor Coluccio Salutati composed epigrams that were to be added to the paintings. In his verses on Cicero, he praises him as “the famous authority of Latin eloquence, Tully, whose talent Rome considered equal to its triumphs and empire; he subdued Catiline, but Antony’s sword killed him and killed freedom” [Hankey 1959, 365]. What Salutati does here is typical for his time: Cicero is presented as fighter for the republic in danger; when he is killed on the instigation of Mark Antony, republican freedom dies with him (a few years after Cicero’s death, Augustus would set up an imperial system in Rome).

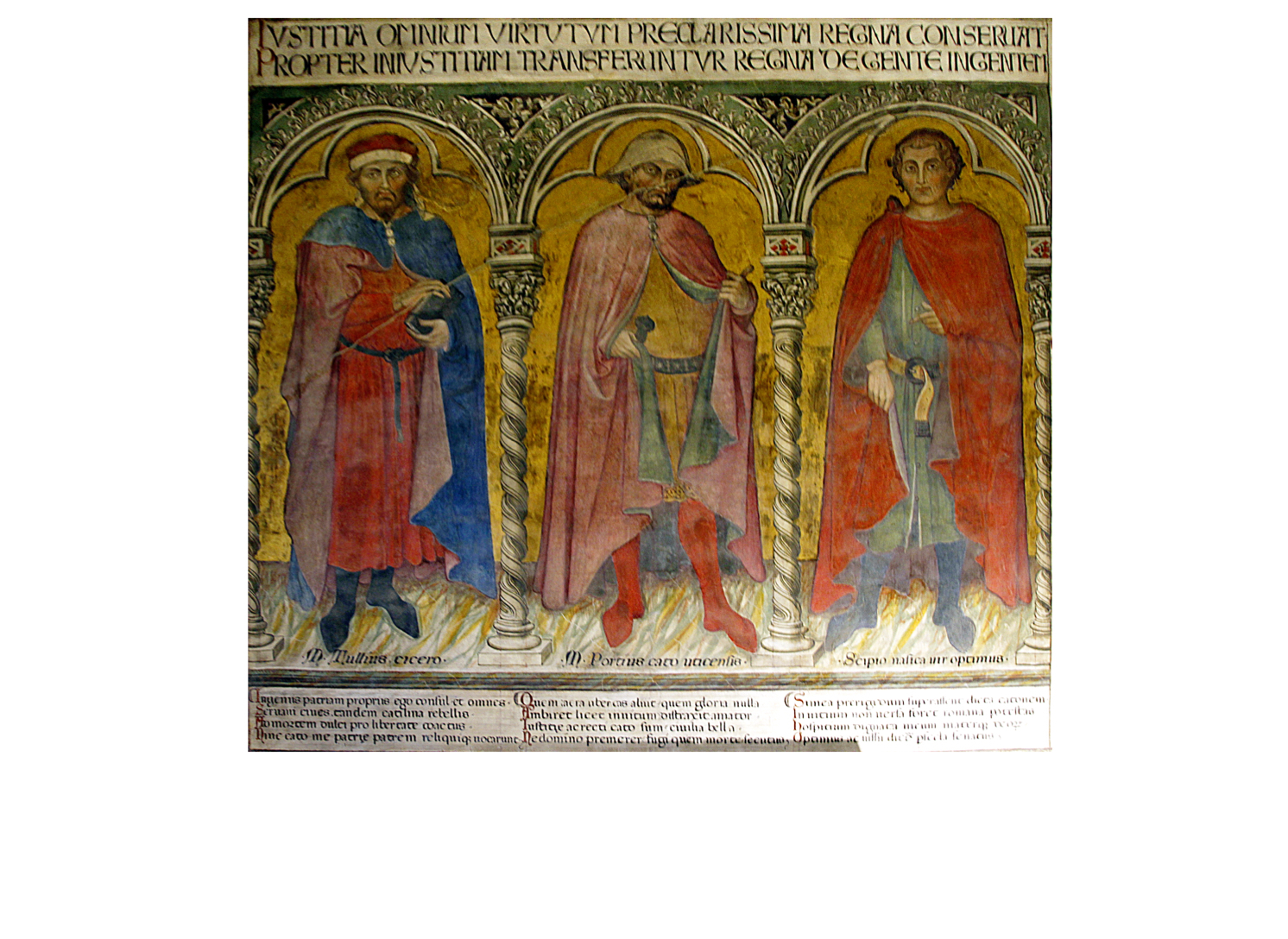

The Florentine frescoes were destroyed during a renovation of the early sixteenth century. But we can get an idea of how they might have looked. One generation afterwards, around 1412, Taddeo da Bartolo painted a comparable cycle of illustrious men in the anticappella of the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. Cicero is depicted on the left. as a man with a beard (a reference, again, to the image of the learned teacher) and positioned next to Cato the Younger, another hero of Rome’s Republican opposition. The epigram underneath (view image in full by clicking on the arrows in the upper right corner to enlarge) stylizes Cicero as martyr for freedom and as the father of the fatherland.

To conclude…

In the Florentine and the Sienese epigrams, Cicero’s life cannot be measured out fully. It is reduced to its exemplary nucleus: his fight for Rome’s liberty and his defence of Rome’s citizens. In the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century, this exemplary reduction goes hand in hand with attempts to contextualize Cicero’s greatness through as much historical detail as possible. The roots for this development, however, was laid in the early fourteenth century – shortly before the discovery of Cicero letters – in the civic culture of the Italian comuni and their striving for new role models.

Further reading:

The Summary of the life, deeds, intellectual excellence, works and death of the very famous and illustrious Marcus Tullius Cicero is edited in: Tilliette, J.-Y. (2003). ‘Une biographie inédite de Cicéron, composée au début du XIVe siècle’, Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 147, 1049–1077.

Colonna’s Life of Cicero can be read in: Ross,W.B. (1970). ‘Giovanni Colonna, Historian at Avignon’, Speculum 45, 533–563.

Salutati’s epigram is edited in: Hankey, T. (1959). ‘Salutati’s Epigrams for the Palazzo Vecchio at Florence’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 22, 363–365.

On the decoration of the Palazzo in Siena, see Rubinstein, N. (1958). ‘Political Ideas in Sienese Art: The Frescoes by Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Taddeo di Bartolo in the Palazzo Pubblico’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 21, 179–207.

The most extensive recent study of Cicero in the late Middle Ages is: Mabboux, C. (2022). Cicéron et la Commune: Le rhéteur comme modèle civique (Italie, XIIIe–XIVe s.). Rome.

Brief, but indispensable is Schmidt, P.L. (2000). ‘Bemerkungen zur Position Ciceros im mittelalterlichen Geschichtsbild’, Ciceroniana n.s. 11, 21–36.

My own article ‘Cicero avant les lettres: Descriptions of His Life in the Early Fourteenth Century (Giovanni Colonna’s De viris illustribus and the Anonymous Vita Trecensis)’ will be published in 2025.

This blog entry presents some results of my NWO Vidi project “Mediated Cicero” (funding no 276–30–013) during which my team and I were able to research the afterlife of Cicero’s historical personality and his rhetorical works in antiquity and beyond.

© Christoph Pieper and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2024. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Christoph Pieper and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.