Coming out of the cave: monks in society in seventh and eighth century Egypt

Starvation, solitude and saintliness. These are not the first words that come to mind when looking at the lives of Egyptian monks in the seventh and eighth century. At least, not when you look at their letters and documents on papyrus and potsherds.

A cave, in the scorching heat of the desert. A long-bearded figure is sitting in front of it. His emaciated body is a testament to his ascetic lifestyle. His face, eyes closed, is radiating holy devotion. Completely immersed in spiritual contemplation, he seems to be unaware of the realities of the world around him.

This image of the ascetic and saintly monk, isolated and withdrawn from society, comes easily to mind when we think of monks in late antique Egypt. This image is inspired by influential early monastic figures, the so-called Desert Fathers, such as Anthony the Anchorite, who retired from the world to spend their life in prayer.

Of course, even in this early period, not all monks lived in complete isolation. The inspirational ascetics attracted disciples, who lived together in more or less loosely organized communities. These different types of monastic lifestyle formed the basis of what it looked like to be a monk in late antique and early Islamic Egypt.

Anthony the Anchorite, ca. 1520, Germany. Picture by elycefeliz: https://www.flickr.com/photos/...

Friends with (spiritual) benefits

In the eighth century, the countryside of Egypt was home to many monasteries. However, monks also lived in looser groups or by themselves. In one of the Pharaonic graves in the neighborhood of modern day Luxor, one monk called Frange lived alone, keeping himself busy with weaving, copying and binding books, practicing his writing skills, and writing letters to his friends. Fortunately, hundreds of letters and other documents, written on ceramic potsherds and on papyrus, have been found in his home. They show us that, while Frange did indeed prefer to stay in his “cave”, he also had a rich social network, in which he played an authoritative role, giving advice on moral issues or interceding for people in trouble. He had a large number of correspondents, male and female, and instead of going out himself, he had them come to visit him. One of Frange’s spiritual pen pals was Tsié, a woman who helped providing Frange’s food and other daily life necessities. In her letters, sometimes accompanying a food delivery, she shows deep respect and concern for him.

God knows the heart of men and knows that I worry about you as I do about my brother. Every time that you say “I am ill”, my heart aches for you.

Tsié also writes letters to Frange for other women, who need Frange’s (spiritual) assistance. The women ask Frange to pray for them and express their hope that his prayers will be heard by God:

I beg you, I bow before you and prostrate myself at your feet. Please pray to the Lord for me, so that he takes pity on me, because I suffer greatly in my body. Maybe God will listen to your prayer and will take pity on me, since I am a sinner.

Frange’s letters to Tsié usually met her respect for him with equal politeness and even warmth. Yet, at one time his bread delivery, for which she was responsible, did not come through, and he reacted with an indignant letter, ending in: “Do I really deserve that you treat me this way, because I am a bitter (read: living a hard hermit’s life) man?”

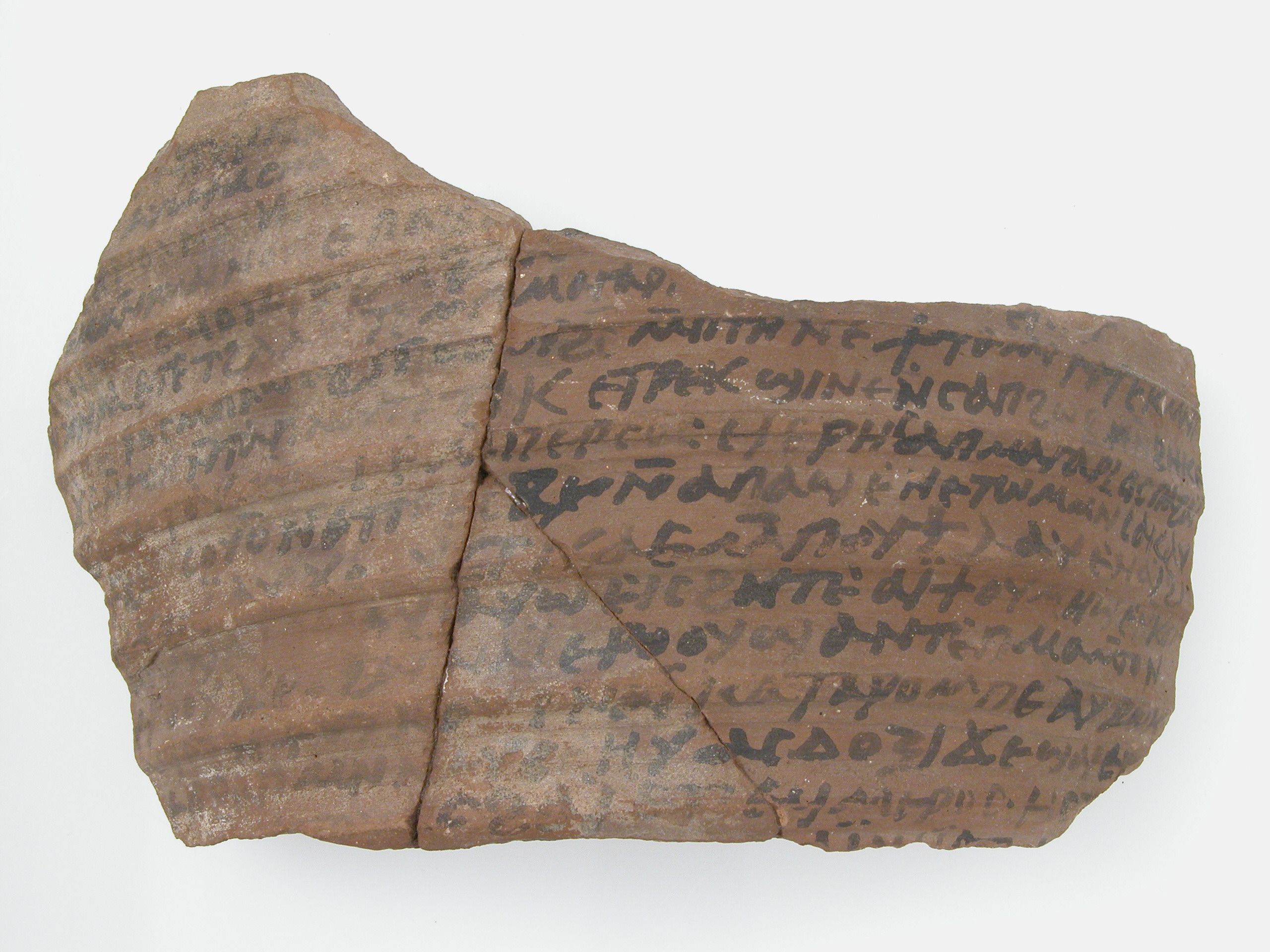

Coptic letter from a woman asking a monk for help. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 14.1.166.

Travelling salesmen

Now that we’ve met a hermit with an impressive social life, let’s turn back to the image of the thin-bodied, long-bearded monk. While some monks certainly must have looked like that, this is what one eighth century monk actually looked like:

Stout, without a beard, tanned, aquiline nosed, with fine eyebrows and a shaven head.

This particular monk lived in the monastery of Saint Jeremiah of Saqqara, 30 kilometers south of Cairo. Home to the famous step pyramid of Djoser, it is also the site of a monastery that by the seventh century comprised churches, monastic living quarters, ovens to bake bread, a refectory, and so on. Our stout and shaven monk’s name was Sampa, son of Kallinikos, and he received a travel permit to go to the South of Egypt for one month, in the company of another monk from the monastery. We know what Sampa looked like because of the physical description on his travel permit, written in Arabic on a piece of papyrus. This physical description served the same purpose as the photographs on our passports and other IDs.

Almost twenty of these early eighth century travel permits, some written for monks and some for lay people, have been deciphered and published today, and more might be waiting in papyrus collections all over the world.

Why were these monks travelling? One very prosaic answer can be found in a request for a travel permit for three monks. They wanted to go from their monastery in the neighborhood of modern day Luxor, to the Fayyum region, about 600 kilometers North down the Nile, to “sell their small amount of rope which is the result of their labors.” One wonders why these monks needed to travel that far to sell their rope, for which there must have been a local market as well. Maybe in the future a newly deciphered document will tell us about the existence of an Annual Rope Fair of the Fayyum, but for now, this aspect of the document remains a bit of a mystery!

Monastery of Saint Anthony, Egypt. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Conflict and negotiation

Selling their products, making money, was a legitimate reason for monks to travel. But they did so also for other reasons. Shenoute was a monk in the monastery of Apa Apollo in Deir el-Bala’izah, about 350 kilometers up the Nile from modern day Cairo. Unfortunately for him, he had had to leave the monastery for less positive reasons than our rope selling monks from the South. In fact, for reasons unknown to us, he had been banished from the monastery. From the letters he wrote to the monastery superior, it is clear that he wanted to return. He wrote, full of guilt:

I know – I, this sinner and disobedient one – that I transgressed all the commandments which you commanded me and I am guilty in every sin.

But apparently someone had told Shenoute that upon his return to the monastery, he would be punished with unpleasant tasks there. This prompted him in his letter to ask his superior to write him a promise that he will be able to live there like all the other monks. His contrition evidently did not hinder him from stipulating conditions for his return. (Spoiler alert: a further letter from Shenoute, still not returned and complaining about his pitiful situation to the superior, shows that the latter did not write said promise – at least not immediately.)

It is clear that all of these monks played an active and integrated role in their communities. They maintained a lively correspondence with the outside world (cave dwelling Frange), and tried to negotiate their way out of an internal conflict (banished Shenoute). But they were also active members of society, who knew very well how to move around in it, as shown by the monks who submitted the right paperwork to the government in order to get the compulsory permit to travel and sell their goods.

Tax evasion

What is the ultimate way to be part of society? Paying your taxes, one could argue. By the end of the seventh century, monks had to pay poll tax to the Arab-Muslim government, like all other adult male non-Muslims. However, it turns out they didn’t always do so. In fact, the community of monks in which our rope making monks lived in the 730s, had taken part in an act of what we could call civil disobedience about 40 years earlier. A Greek letter, issued by a high administrative official of the Arab-Muslim government, reprimands the monks, but also promises them protection, if, however, they pay their poll tax and don’t cause any more trouble.

I permit you to stay in your home as you did until now, without harassment, and to take note that I will not suffer anyone to transgress against you, on condition, however, that you continue to live peaceably and pay your poll tax, in which you defaulted as said during the period of the insurrection.

The scenes which I have sketched above, and which are provided to us through documents on potsherds and papyrus, are colorful and convincing counterexamples to the stereotypical image painted in the introduction to this blog. These monks were an integral part of the fabric of their communities and of society at large, in constructive and sometimes less constructive ways.

Sources:

Documents cited, in order: O.Frange 254, 265, 331,P.RagibSauf-conduits 7, P.CLT 3,P.Bal. 2 188, SB 3 7240.

For the abbreviations of the editions, see the checklists of the Greek and Coptic documents, and of the Arabic documents.

© Eline Scheerlinck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Eline Scheerlinck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.