Curious drawings in a medieval account book, part 2: Foyken’s gnome

On a small drawing in an account book and the practicalities of auditing.

10 December 1372. With a slight hesitation, Foyken Willemszoon enters the chambers of the tresorier of Holland in The Hague. For the fourth time, he has to give account and explanation before the council of Albrecht, count of Holland, for the way he had managed his district as steward. A year long he had toiled to balance the count's income and expenditure in the Northholland district. To no avail. Like the previous years, his account shows a large deficit. During the session, his account will be reviewed point by point to make sure that income and expenditure have been recorded correctly. Of course, he has prepared well: he carries his account in duplicate, along with some receipts to support it. He has even added some nice little drawings in his account book, hoping the committee would appreciate them. But was it substantial enough for the auditing committee chaired by the unapproachable tresorier Conrad of Silice?

As modern historians, we can note that Foyken's account is rather unspectacular as a financial document. It is part of a long series of accounts of the then stewardship of Northholland, an area largely corresponding to the present-day province of South-Holland. It contains a recording of the annual tallying up of income and expenses, mostly of an agrarian nature, ending in a substantial deficit. It is not the repetitive lists of revenues and expenses or the financial balance sheet that catches our attention, but the fact that Foyken added a number of tiny drawings of men and women to his account, somewhat similar to the drolleries that are occasionally added to the margins of manuscripts. Two of these are of special interest.

The drawings in Foyken’s account

Illustration 1 is an enlarged reproduction of one of these drawings. We see a man with thinning hair and a serious expression on his face, half-hidden behind the capital letter S of Summa. The man is pointing at the Roman numeral III. This numeral marks the sum of the third chapter of income collected by Foyken. The drawing is not entirely clear, but it appears that the man has his index and middle fingers stretched out, his thumb is pointing up, and his ring finger and little finger are curved. It seems to be the same oath-swearing gesture that is depicted in the Sachsenspiegel-manuscript and comparable to the one in Heynric van Dronghelen’s account (see the previous blog).

This interpretation is confirmed by Foyken’s drawings a few pages down in the same account book (illustrations 2a and 2b). At the top of the page, the fifth sub-total of the account is shown, marked with the Roman number V. It shows a sad-looking man with large ass’s ears. Is this a reference to Koning Ezeloor (King Ass’s ear) who was known as one of the ancestors of the Hollanders, or to King Midas from Ovid's Metamorphoses, who turned everything he touched into gold? The latter interpretation would give an interesting insight into Foyken's aspirations as a steward. Underneath we can see a large cross and a large letter S. Inside the letter S another face appears, watching the scene. Half hidden behind the letter, we observe a gnome-like character with a beard and a pointed cap – is it Foyken’s self-portrait? He is holding a bell in his left hand and pointing at the cross with his right hand. When we zoom in close enough, we see that the figure is also pointing with both his index and middle finger, thumb up, and keeping both other fingers curved (illustration 2b).

This image leaves little to the imagination. Just like in Heynric’s account book, this gnome is taking an oath. He accompanies his oath – puts an exclamation mark behind it, as it were – by ringing a bell. The person inside the letter S is watching while the oath is being taken. The oath should relate to the adjoining text containing the summa summarum van alle Foykijns ontfanghe, the grand total of all Foyken’s income, stating that he had received for his master an income of 6262 pounds over the year 1371-1372. The question then is, how common was this? By pointing at the cross, the gnome shows us the way. Literally.

Crosses in accounts

In the account books, we rarely come across drawings of people taking an oath, but crosses abound. They appear in the oldest surviving accounts audited by the counts of Holland and their council. Let us take the series of the account books of the steward of Northholland, to which Foyken’s account also belongs, as a point of departure. The oldest one covers the year 1316-1317, it was drawn up by a certain Enghebrecht. It contains no fewer than eleven crosses, always placed next to the totals or sub-totals. Figure 3 shows an example of two crosses, the upper one placed next to the sub-total of the taxes of two districts, the lower one next to the grand total of all income.

Enghebrecht’s is the first of a long series of account books handed in by the successive stewards of Northholland. For the period up to 1416, there are 57 accounts, drawn up by 23 different stewards. Until 1416, all these accounts contain crosses. Initially these were simple drawings of Latin crosses, as in the account of the year 1316-1317, but from 1370 onwards, the crosses become increasingly elaborate and appear to have been drawn after real models: a pedestal is added, and sometimes the arms of the cross are adorned with what appear to be precious stones. A colourful collection of Latin crosses, processional crosses and reliquary crosses unfolds. Illustrations 3-6 give a short impression of the different designs we encounter. The stylistic excess reaches its peak shortly before 1420 (compare illustration 6) and then it suddenly stops. In the margin of the summa summarum of 1421-1422, a very last cross has been drawn by the acting steward, very thinly, almost hesitantly (Illustration 7).

- Illustration 4. Subtotal and Summa summarum of the account of the stewardship of Northholland, 1347. National archives The Hague, Graven van Holland (3.01.01) 1438, f. 34r.

- Illustration 5. Summa summarum of the account of the stewardship of Northholland, 1381-1382. National archives The Hague, Graven van Holland (3.01.01) 1460, f. 35r.

- Illustration 6. Summa summarum of the account of the stewardship of Northholland, 1414-1415. National archives The Hague, Graven van Holland (3.01.01) 1489, f. 28v.

- Illustration 7. Summa summarum of the account of the stewardship of Northholland, 1420-1421. National archives The Hague, Graven van Holland (3.01.01) 1494, f. 70v.

The use of crosses as images accompanying the summas is not limited to the accounts of the stewards of Northholland. They can also be found in the accounts of the stewards of Kennemerland-Westfriesland (period from 1343 to 1404), of Southholland (from 1331 to 1386) and occasionally in the accounts of Forester. Interestingly, they are only rarely added to the account-books of the officers of the Count’s inner circle, the Count’s treasurer and the clerk of the Household.

Oaths and crosses

Oath and cross are connected, that is what Foyken’s gnome shows us. A res sacra, a holy object, was indispensable for the sealing of an oath. It sealed the covenant that the person swearing an oath made with the person who received the oath. This holy object could be a reliquary of some local saint, a part Gospel Book, or a crucifix. There is evidence that such crosses were sometimes available in the late medieval chambers where the accounts were audited. When, for instance, in 1352 a Burgundian Audit Office was established in Dijon, the auditors set out to buy three Gospel Books and a golden crucifix.

There may have been a crucifix in the Holland treasurer’s office when Foyken entered it in 1372, and it is possible that he drew the cross after this model. However, the stylistic diversity of the drawings suggests that there was not a single cross that was used as a model by him and his colleagues. It is more likely that the crosses were drawn before, when the steward wrote down his account and prepared for the audit session. The gnome, part of the penwork around the letter S, points to that. Literally. By drawing a cross, Christ was invocated as a witness of the truth, as is shown by the many chrismons that were drawn in administrative documents.

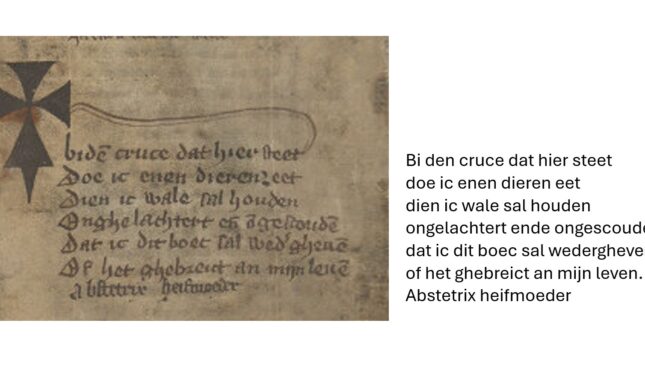

A fascinating example of this can be found on the last page of one of the highlights of the British Library, a lavishly illustrated manuscript of Jacob van Maerlant's Der naturen bloeme. The manuscript itself dates from the fourteenth century; in the fifteenth century it was apparently borrowed by an unknown lady who swore on a cross that she would return it:

On the cross that is drawn here

I take the solemn oath

that I will keep well

unbroken and untouched

that I will return this book

or I will give my life for it.

Abstetrix midwife

Conclusion

Back to the moment that Foyken entered the chambers of the Tresorier of Holland with his account. He may have been worried about the audit and about the councillors' reaction to his deficit; the underlying documentation may have been deficient. But he and his auditors were convinced that there was One who sees all. This is nicely reflected in a reliquary cross drawn two decades later by one of Foyken's successors as steward of Northholland. A face can be seen in the middle of the cross, the location where the relic was normally placed (illustration 9).

Further reading

- M.T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record. England 1066-1307 (3rd edition Oxford 2013).

- D.E.H. de Boer, ‘Illumination of Accounts, Decorative Tradition in the Accounts of Holland, ca. 1360-1420’, in: D. van der Horst, J-C. Klamt (eds.), Masters and Miniatures (Doornspijk 1991) 303-314.

- Anne-Maria van Egmond, Materiële representatie opgetekend aan het Haagse hof, 1345-1425 (Hilversum 2020).

- H. Jassemin, ‘Le contrôle financier en Bourgogne sous les dernier ducs capétiens (1274-1353)’ Bibliothèque de l’Écoles des chartes 79 (1918) 102-141.

- Kathryn M. Rudy, Touching Parchment: How Medieval Users Rubbed, Handled, and Kissed Their Manuscripts Volume 2: Social Encounters with the Book (Cambridge UK, Open Book Publishers, 2023). https://www.openbookpublishers...

© Robert Stein and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Robert Stein and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.