Female f(r)iendly: Early medieval English remedies for managing menstruation

What was it like for women to get their period in early medieval England? What does Anglo-Saxon medicine tell us about their understanding of the menstrual cycle? This post traces early medieval attitudes on female genitalia and analyses Old English remedies dealing with menstruation.

The ‘Curse’ of Womanhood

While menstruation is a physical discomfort that women of all time periods go through for about thirty to forty years of their lives, Anglo-Saxon women did not have access to Advil to alleviate their menstrual pains, nor did they have the luxury of finding tampons in vending machines in public bathrooms. Besides, it was not socially acceptable to discuss their feminine organs in public. In fact, the topic of menstruation was often buried in shame and embarrassment, even for scribes and translators of medical texts.

Books such as The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation (1988), and The Medieval Vagina: An Historical and Hysterical Look at All Things Vaginal During the Middle Ages (2014) prove that nowadays we can openly discuss (female) genitalia and, more importantly, that we are interested in how our ancestors coped with menstruation and dealt with ‘all things vaginal’ (Harris & Caskey-Sigety; Delaney, Lupton & Toth). However, as especially the first book title emphasises, menstruation had – and in some cultures still has – a rather negative connotation, which stems from an ancient belief that menstrual blood was cursed, filthy and had “dangerous effects” (Horden: 14).

This irrational fear of the female menstrual cycle is not the only reason why women are underrepresented in Anglo-Saxon medical texts; some texts on gynaecological medicine have, unfortunately, not survived the centuries (Cameron: 40). Still, by tradition, medicine was predominately concerned with male health and was written down by male monks. Therefore, in order to gain insight into early medieval understandings of the menstrual cycle, this blog post examines the importance of blood in Anglo-Saxon medicine and analyses several Old English medical texts that explicitly mention menstruation and provide remedies for either stimulating or stopping the flow of menstrual blood.

A Bloody Business

Whereas blood is still a rather important part of medicine today, it also played an essential role in the medieval practice of bloodletting. Following Galen’s humoral theory, blood was considered one of the four bodily humours alongside yellow bile, black bile and phlegm (Kesling: 18). In order to be completely healthy and in balance, all four humours needed to be equally represented in the body. Therefore, if you had too much heat (e.g. a fever) in your body, bloodletting could help to restore this balance (especially since blood was considered one of the hot humours).

While bloodletting is not often and not necessarily linked to menstruation, it could provide an answer as to why menstrual blood was considered impure and dangerous in the early Middle Ages, as it would leave the women, according to Galen’s theory, imbalanced.

Cures for the Curse

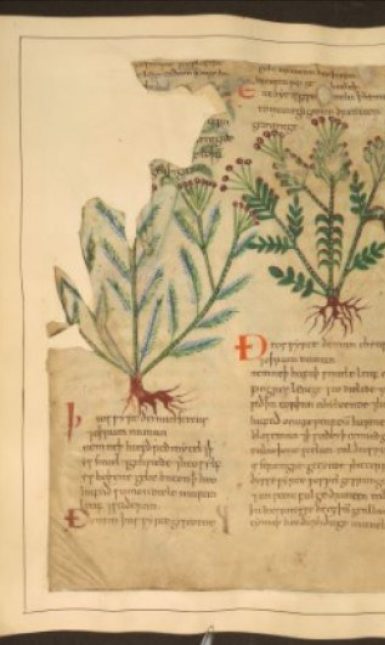

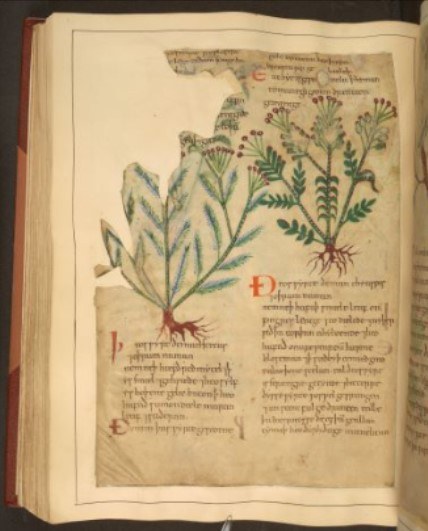

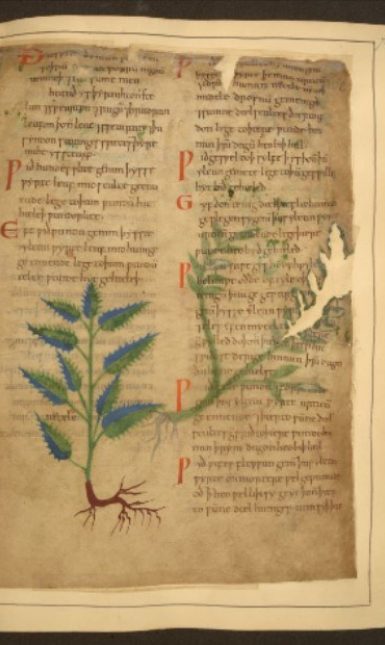

The translator responsible for the Old English Herbarium, an eleventh-century translation of a Latin original, excluded a remarkably high number of remedies related to the female sex (Kesling: 145). Luckily, he or she did not omit all cures or phrases related to women and, in particular, the translator appears to have retained some remedies that deal with menstruation.

The first two examples are nearly identical, and both aim to stop the flow of menstrual blood:

“For a woman's menses, take the confirma [comfrey] plant, pound it into fine powder, and give it to drink in wine. The flow will quickly stop.” (trans. van Arsdall: 175)

“For a woman's menses, take the plant called sinfitus albus or comfrey, dry it, and pound it into fine powder. Give it to drink in wine, and the flow will quickly cease.” (trans. van Arsdall: 203)

Medical historian Anne van Arsdall, who provided this Modern English translation, notes that “[h]eavy or prolonged flow is implied, or it would not need to be stopped”. A significant point to notice here is that the creator of these two remedies evidently believed that women are capable of stopping menstrual blood prematurely, while heavily flowing, instead of having to wait for the period to naturally cease.

The effect of the next remedy is twofold, as it does not only stimulate the menstruation, but it also eases the pain. It is remarkable that we do not find pain killing as a key aspect in many cures involving menstrual issues, given the fact that most modern medicine is focussed exclusively on pain relief. However, the remedy does not explicitly state that the taking away of “all painful congestion in the abdomen” also concerns the “woman’s menses”. The ambiguous phrasing of this cure makes that it could also comprise two different medical issues:

“This plant, which is called thyaspis […] takes away all painful congestion in the abdomen and it also stimulates a woman's menses.” (trans. van Arsdall: 215)

The following remedy urges women to lay a plant under their genitals, which is significantly different from the powdered wine examples mentioned above:

“This plant, which is called hypericon or corion because it looks like cumin, has leaves like rue, and many branches grow from one stalk and they are red. It has flowers like a wallflower, and round, somewhat long berries, like barley, on which is the seed, which is dark and smells like wood. It grows in cultivated places. pounded and drunk, this plant stimulates urination, and it brings on the menses very well if it is laid under the genital organs.” (trans. van Arsdall: 216)

The redness of the branches illustrates an instance of sympathetic magic (i.e. treating like with like). While sympathetic magic is fairly common in early medieval medicine, this is, somewhat surprisingly, the only menstruation remedy that explicitly mentions the colour red. The other cures focus mainly on the qualities of the plants involved.

One more example from the Old English Herbarium is another remedy for stopping the blood flow:

“For a woman's menses, take the same plant [called urtica or nettle], pounded thoroughly in a mortar so that it is very soft. Add to it a little honey, take some moist wool that has been teased, and then use it to smear the genitals with the medication. Then give it to the woman, so that she can lay it under her. That same day, it will stop the bleeding.” (trans. van Arsdall: 226-227)

This cure stands out due to its use of the nettle plant, which causes severe itching. The addition of honey probably reduces the stinging of the nettle leaves, but it is still an interesting choice of plant, considering the many alternatives as presented above.

In several footnotes throughout her 2002 translation of the Old English Herbarium, Van Arsdall informs us that the first editor and translator of this text, Thomas Oswald Cockayne (1807-1873), consistently translated the word for “menses” into Greek, which proves that even in the nineteenth century, the shame for discussing menstruation in the public sphere was still very much present. Likewise, Cockayne used the word “naturalia” to describe the genital organs and he translated the entire passage of the last mentioned nettle remedy into Latin, which portrays how deeply the taboo is embedded in history.

Cockayne’s unease with menstruation also comes to the fore in this last example, taken from his translation of the eleventh-century Old English Medicina de Quadrupedibus:

“At si hoc optaverit, ut menstrua fluant, let her comb her head again under the mulberry tree, and let her collect the hair that cleaveth upon the comb, and let her place it on a twig which is turned downwards, and let her collect it again ; that is her leechdom.” (Cockayne: I:333)

Cockayne here translates the Old English phrase describing menstrual flow into Latin rather than in Modern English as he did for the rest of the remedy proper. Moreover, this particular remedy has distinctly less medicinal and more folkloric, possibly magical elements to it, demonstrating that some early medieval people regarded menstruation so accursed, that they turned to wizardry rather than to herbs.

As this blog post has demonstrated, several remedies from early medieval England dealt with menstruation, albeit probably mainly from a male perspective. Intriguingly, while a nineteenth-century scholar felt ashamed to fully translate these Anglo-Saxon texts into Modern English, the early medieval translator apparently did not share this unease – so perhaps, after all, this was not such a dark age or, indeed, period!

Bibliography

van Arsdall, Anne, Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine. Routledge, 2002.

Cameron, M. L. Anglo-Saxon Medicine. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Cockayne, Thomas Oswald. Leechdoms Wortcunning, and Starcraft of Early England Being a Collection of Documents, for the Most Part Never Before Printed Illustrating the History of Science in this Country Before the Norman Conquest, 3 vols. Longman and others, 1864–6.

Delaney, Janice, Mary Jane Lupton and Emily Toth. The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Harris, Karin, and Lori Caskey-Sigety. The Medieval Vagina: An Historical and Hysterical Look at All Things Vaginal During the Middle Ages. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014.

Horden, Peregrine, “What's Wrong with Early Medieval Medicine?,” Social History of Medicine 24 (2011)

Kesling, Emily. “Introduction,” in Medical Texts in Anglo-Saxon Literary Culture. Boydell Press, 2020.