Hogwarts in the Middle Ages: Piggy Place Names in Early Medieval England

What are the medieval origins of Harry Potter's Hogwarts and how do place names reveal the importance of pigs in medieval culture?

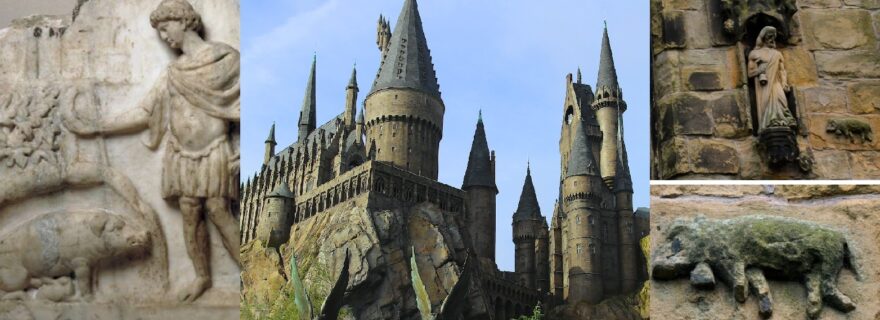

Pig Marks the Spot: An Uncertain Etymology and Echoes of Virgil

The exact etymology of the name Hogwarts for Harry Potter’s famous wizarding school is unknown. There seems to be an obvious connection to pigs, given the element ‘hog-‘, which is also picked up by translations of the school’s name in various languages, such as French Poudlard (pou-de-lard ‘bacon lice’) and Dutch Zweinstein (zwein is a homophone of Dutch zwijn ‘swine’). Nevertheless, J. K. Rowling herself has indicated that she believes she may have been subconsciously inspired by the name of a plant rather than a pig: hogwort (the hog-element in that plant’s name may derive from its ‘porcine smell’). The in-world explanation of the name, however, clearly links the name, as well as the school’s location, to a pig. Rowena Ravenclaw, one of the four founders of Hogwarts and living in the tenth century, is said to have had a dream of a “warty hog” that led her to the location where the school was founded and inspired her to name it Hogwarts (on the founders of Hogwarts, see this feature on ‘Wizarding World’).

The idea of pigs indicating good building locations is not unique to Rowling: it can be traced back to Virgil’s Aeneid. In Book VIII, Virgil relates how, in a dream, Aeneas was advised to build his new city in Italy on a site where he would find a white sow with thirty piglets:

And now, lest you think this sleep's idle fancy, you'll find

a huge sow lying on the shore, under the oak trees,

that has farrowed a litter of thirty young, a white sow,

lying on the ground, with white piglets round her teats,

That place shall be your city, there's true rest from your labours.

(Virgil, Aeneid, trans. A. S. Kline (2002), book VIII)

This founding legend was copied and adapted by many medieval authors, notably hagiographers, to describe how certain saints built their churches on places where they encountered pigs, as Karen Jankulak (2003) has shown. The Celtic saint Brannock, for instance, builds his church on a spot where he find a white sow with her farrow, as do saints Baglan, Cyngar, Dyfrig and Piran. The legend also pops up in England, where Glastonbury is said to owe its name to a man named Glæsting, whose lost sow had led him to an apple-tree near an old church, where he subsequently settled (this story is first recorded by 12th-century chronicler William of Malmesbury). A similar, but more elaborate, story is linked to the etymology of Evesham as will be shown below, but not before we have looked at less legendary swine.

The Pig’s Place in Old English Toponymy

It was not just legendary sows that gave their names to places. Old English toponyms (place names) reveal that various pigs were immortalized by the early medieval settlers who named places that were, apparently, characterised by the presence of swine. Cases in point include such place names as Barlow (< OE bar+leah 'boar clearing'), Barwell (<OE bar+wella 'boar spring'), Borley (<OE bar+leah ‘boar clearing’), Everton (<OE eofor+tun ‘boar settlement’), Swindon (<OE swin+dun ‘pig hill’), Hogshaw (<OE hogg+sceaga ‘hog wood’) and Sugley (<OE sugu+leah ‘sow clearing’). Place names such as these, can tell us something of the flaura and fauna that the Anglo-Saxon settlers saw around them when they arrived in early medieval England – Everleigh, Evershot, Everdon, Swinford, and Hoggeston were places were pigs would have roamed large. Some place names also tells us something of how various groups within medieval England co-habited, as they show combinations of place name elements in different languages: Swinscoe, for instance, is a combination of Old English swin ‘swine’ and Old Norse skogr ‘wood’; Hogsthorpe shows a similar combination of an Old English word for pig with Old Norse thorp ‘settlement’. By contrast, Swyncombe may be a combination of Old English swin and Welsh cumm ‘valley’. You can find out more about early medieval English place names here: What’s in a place name? The toponymy of early medieval England.

Named for a Swineherd: The Etymology of Evesham, Worcestershire

Sometimes, it is not the swine but the swineherd that is commemorated in a place name. Such appears to be the case in Evesham, at least if we are to believe a story told by Byrhtferth of Ramsey (c. 970–c. 1020). In his Vita S. Ecgwini, an account of the life of Ecgwine, bishop of Worcester (?693–717) and founder of Evesham Abbey, Byrhtferth included the following anecdote:

Saint Ecgwine had acquired a piece of land full of leavy woods and thick brambles. He appointed four swineherds, each with their own herd of pigs: Ympa, Trottuc, Cornuc and Eoves. It is from this last swineherd that Evesham gets its name. Here is how it happened:

“[A] sow belonging to the man called Eoves, when the time for giving birth had arrived, hid herself secretly, and stretched out, pregnant, in the thick brambles of that forest, without her custodian knowing it. And he waited for two or three days, expecting and hoping that she would come to him in her usual manner, which in no way took place. […] Then after the passage of a few days, while that devout man was everywhere traversing paths that were no good, he finally saw his sow coming ahead of him out of the forest, not alone but having seven piglets with her. He expelled all the glaucoma and pain from his eyes. He called her by her name. Hearing the familiar voice from a distance she came happily to him, falling at his feet. She began straightway to suckle her piglets.” (trans. Michael Lapidge, Byrhtferth of Ramsey: The Lives of Saints Oswald and Ecgwine (2008), pp. 245-247)

The next time the sow had to give birth, the same thing happened: she went to her secret hiding place and a few days later she came out, with eight piglets (all of which were white, except their ears and feet). When the sow disappeared for a third time, Eoves started looking very carefully for her and found her secret hiding place, where she lay with nine piglets. But then, something miraculous happened.

In the sow’s secret hiding place, he saw a vision of the holy virgin Mary. Eoves reported his vision to Ecgwine, who then went to the sow’s hiding place and also has a vision of the Mother of God. It was there that Ecgwine later founded a church and some monastic buildings, which became known as Evesham Abbey. Clearly, Byrhtferth’s story of Eoves’ sow has some faint echoes of Virgil’s Aeneid but is much embellished – I particularly like such details as the swineherd calling one of his sows ‘by her name’ and that the pig responded to this.

Oink Oink? The Origins of Winwick, Cheshire

A final piggy place name concerns the town of Winwick, Cheshire. The story of the town’s name is linked to a pig who disrupted the building of a church in honour of the Northumbrian king and saint Oswald (d. 642). The legend is recorded as follows:

“The parish church of Winwick stands near that miracle working spot where St Oswald, King of the Northumbrians, was killed. The founder had destined a different site for it, but his intention was overruled. Winwick had not then even received its name, the church being one of the earliest erections in the parish. The foundation of the church was laid where the founder had directed; and the close of the first day’s labour showed that the workmen had not been idle by the progress made in the building. But the approach of night brought to pass an event which utterly destroyed the repose of the few inhabitants around the spot. A pig was seen running hastily to the site of the new church; and as he ran he was heard to cry or scream aloud, " We-ee-wick, we-ee-wick, we-ee-wick." Then, taking up a stone in his mouth, he carried it up to the spot sanctified by the death of St Oswald, and thus employing himself through the whole night, succeeded in removing all the stones which had been laid by the builders. The founder, feeling himself justly reproved for not having chosen that sacred spot for the site of his church, unhesitatingly yielded to the wise counsel of the pig. Thus the pig not only decided the site of the church, but gave a name to the parish.” (,John Harland and T. T. Wilkinson, Lancashire Legends (1873), via https://www.mysteriousbritain.co.uk/ancient-sites/st-oswalds-church-winwick/ )

The pig’s role in choosing the location of the church is commemorated by a relief of the Winwick pig in the tower of St. Oswald’s church in Winwick:

Let us finally return to J. K. Rowling’s Hogwarts, which may owe its name and location to Rowena Ravenclaw’s dreaming of a pig. As this blog post has demonstrated, this motif of a location-indicating hog may find its origin in Virgil, but it is certainly not out of place in a story about the tenth-century British origins of a legendary school!

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.