"Horribiles vultus": race and racism in Byzantine Africa

A passage in a sixth-century epic narrative ‘On the Libyan War’ reveals the role of race and racism in defining communities in Byzantine North Africa.

For today’s blog article I wanted to discuss a somewhat uncomfortable anecdote that I encountered a couple of years ago while writing my master’s thesis. Uncomfortable, because the anecdote tells a chilling account of people being discriminated against on the basis of the colour of their skin. Nevertheless, it is a story worth telling because it shows that the history of race goes back a long time. Racism is not (just) a modern phenomenon, but rather aspects of it can already be found in the medieval and classical pasts.

Moorish wars

The story takes us back to Byzantine North Africa in the sixth century, an area comprising roughly modern day Libya, Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco (but not Egypt). The area, especially around Tunisia, had previously been one of the most prosperous territories of the Roman Empire, providing the Western Empire with a stable supply of tax revenue and grains.

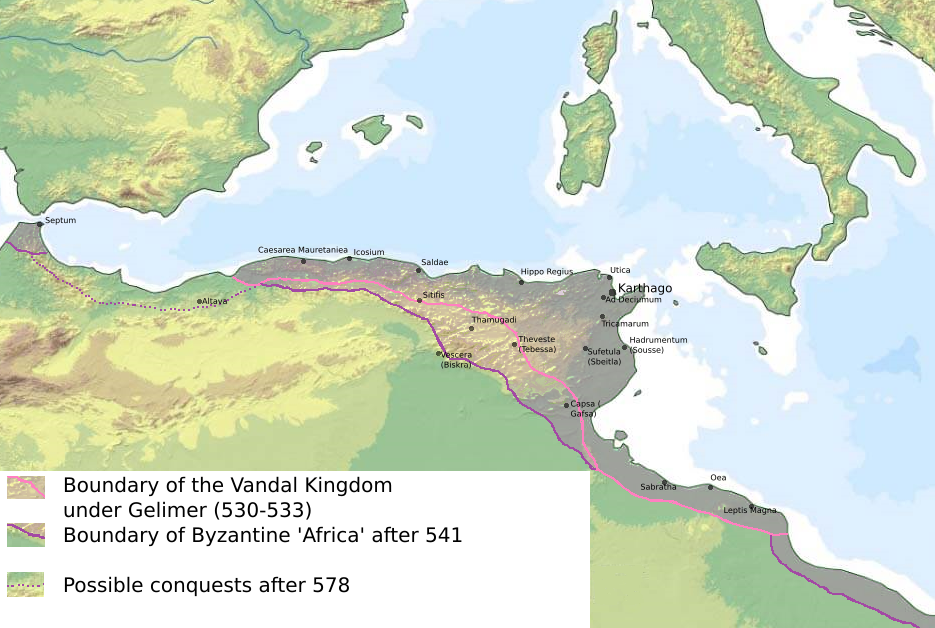

Unsurprisingly, then, it was a huge blow to the Empire when it was conquered by the invading Vandal peoples, who coming from Europe, crossed the strait of Gibraltar in 429 and established their own Vandal Kingdom of Africa for the next century or so. This lasted until 533, when the Eastern Roman (i.e. Byzantine) emperor Justinian sent an army from Constantinople to ‘reconquer’ the former Roman province of Africa.

Map showing the outlines of Vandal (pink) and Byzantine (purple) Africa. The Moorish kingdom(s) could be found south of the pink line. Source: Wikimedia

The Byzantine reconquest was swift and efficient, taking only a few months from the moment the fleet sailed from Constantinople in June until the defeat of the Vandals and the capture of their capital city Carthage in December. What proved more difficult, however, was maintaining control over their (re)conquest, as the next one and half decade was filled by a series of rebellions by indigenous tribes described by our sources as Mauri, ‘Moors’, related to the modern day Berber peoples.

The Mauri had established one or more of their own kingdoms (how many exactly is a subject of scholarly debate) in the North African hinterlands, among the inaccessible passages of the Atlas mountains and on the edge between the fertile coastal zone and the Sahara desert. From here, they raided the agricultural plains of Africa, forcing the Byzantine authorities to respond in force. Finally, in 546, emperor Justinian sent General John (Iohannes) Troglita, who was ultimately able to defeat the Moors in a series of battles, ending a long period of violent unrest.

Old postcard, depicting the ruins of a Byzantine church in Carthage.

Blackness in Corippus

John Troglita’s military successes led to the honour of becoming the main subject of an epic commemorating his exploits, called the Iohannes or The Libyan War (‘De Bellis Libycis’). Written by the Roman-African author Flavius Cresconius Corippus and composed in the style of the Roman poet Virgil, the Iohannes gives us a detailed look at John’s campaign. Corippus himself gave a local perspective on the conflict between Byzantium and the Moors, but he clearly favoured the former over the latter. Many of his descriptions of the Mauri are defamatory and extremely negative. Some of them turn out to be outright racist.

The most overt example is a passage that describes general John parading through the streets of Carthage with a multitude of Moorish prisoners, captured during the most recent military campaign. The crowds came out in droves to watch the spectacle. It is at this point that Corippus makes a remark on the skin colour of some of the Moorish prisoners:

‘Nor were all the captives of the same color. There sat a woman, horrid to behold, the same color as her black children [illa sedet cum nigris horrida natis]. They were like the young of crows, whom you can see turning black [nigrescere] as their mother sits above them, holding out to their open mouths the food they eat each day and lovingly embracing them with her outstretched wings. And while mothers and fathers took pleasure in showing these horrible faces [horribiles vultus] to their little children, the great-souled leader (general John, red.) passed beneath the threshold of the temple with his standards.’

- Corippus, De Bellis Libycis, 6.92-98, edited and translation by G.W. Shea.

Corippus’ anecdote clearly has a hostile attitude. The black mother and her children are shamed and ridiculed. Corippus uses the dark colour of their skin to depict the Moorish enemies as the quintessential other: different, exotic and even horrifying.

The negative association of dark skin colour is found also in an earlier passage. While general John is sailing from Constantinople to Africa, he is visited by two nightly apparitions. One is a white, angelic spirit who lifts John’s spirits and encourages him. The other is a dark spirit, its grim form ‘akin to darkness. Its face seemed Moorish, fearful in dark colour’ [Maura videbatur facies nigroque colore horrida]. (1.245-6).

On the other hand, these passages also informs us that the skin colour of some North Africans was, indeed, black. This may seem obvious, but it affirms the presence of people of colour in the history of the Byzantine and early medieval world. In Roman times, travel between the provinces was commonplace, but even after the “fall” of the Western Empire in the fifth century, people could travel over large distances.

One noteworthy example is a man called Hadrian, described by Bede as vir natione Afir (‘a man of African race’) who fled Africa in the seventh century and ended up as abbot of a monastery in Canterbury, England. Hadrian is often mentioned in debates on racial diversity in early medieval England. While we cannot be sure about the colour of his skin, the evidence shows that we cannot automatically assume his whiteness.

A fifth-century portrait from the catacombs of San Gennaro in Naples. Believed to represent the African bishop Quodvultdeus, who was bishop of Carthage before he was exiled to Naples after the Vandal conquest of Carthage in 439. Source: Wikimedia.

Racism in classical literature

Corippus wrote according to the traditions of classical Greek and Roman literature, so to place his racial attitudes in context it is also important to consider race within the literary tradition that he inherited. Traditionally, scholars have tended to downplay the presence of racism in Graeco-Roman society. According to conventional wisdom, Greeks and Romans did not see colour.

It would go too far to recap the entire debate here. I just want to briefly note two scholarly contributions that show the field has been shifting.

First is the work by Benjamin Isaac, who has argued that there was a form of ‘proto-racism’ in classical Antiquity (Benjamin 2006). Greek and Roman literature, according to Isaac, does show prejudice towards entire peoples and a belief that someone could be inferior based on their place of birth and lineage. In fact, unlike Isaac, some people now argue we might as well drop the label ‘proto’ and simply call it racism.

Secondly is the scholarship by Shelley P. Haley, who likewise shows that Romans were aware of differences in skin colour and used it to construct difference between themselves and outsiders (Haley 2009). Also, Haley uses the lens of Critical Race Theory to argue that white scholars of the 19th to 21th centuries have inserted their own ideas about race into their reading of Graeco-Roman literature and the whitewashing of classical heritage; a lesson that medievalists may want to take to heart as well.

Nevertheless, the colour of someone’s skin was not the main defining quality of ethnic stereotypes, as it would be in modern times. Instead, race was part of wider set of ideas about culture, sexuality, gender and class that was used to create negative stereotypes of outsiders.

Stereotypes

The same is true for Corippus’ description of the Mauri. Only rarely does he use skin colour to create a sense of difference between Roman and Moor. More generally he relies on a set of negative stereotypes, also inherited from classical literature, that shows the Mauri as deprived and uncivilised people. Corippus’ contemporary author Procopius views the Moors in a similar way, as barely distinct from wild animals:

'The Berbers live in stifling huts […] And they sleep upon the ground […] laying a sheepskin under themselves. Their custom is not to change their clothes with the seasons, but they wear a thick cloak and a rough tunic all the time. And they have neither bread nor wine nor any other good thing, but they eat their grain, either spelt or barley, neither boiling it nor grinding it into meal, nor at all differently than the other animals.'

- Procopius, De Bello Vandalico, 2.6.5; 2.6.10-13

In table 1, I have summed up a number of examples that show how a set of negative traits created an image of the Mauri as wild, savage and alien. I want to stress here that these descriptions are in the first place fictional, discriminatory stereotypes used by sixth-century intellectuals to paint a negative image of their “barbarian” enemies in war propaganda, and not a true reflection of the historical Berbers.

Craven |

Fleeing, unfair fighting |

Corippus, Iohannis 5.154‑155, Procopius, BV 2.11.47‑56 |

Faithless |

Breaking promises |

Corippus, Iohannis 1.522‑578, BV 2.8.9‑11, Procopius, BV 2.25.16 |

Cruel |

Burning, slaughtering, pillaging |

Procopius, BV 2.23.26‑27, Corippus, Iohannis 3.380‑400. |

Innumerable |

Innumerable armies |

Corippus, Iohannis 2.196‑196, |

Irrational |

Howling at each other |

Corippus, Iohannis 4.350‑355 |

Uncivilised |

Not wearing proper clothes, not eating proper food |

Corippus, Iohannis 4.350‑355, Procopius, BV 2.11.26, 2.6.5‑13. |

Black-skinned |

Roman mothers scare their children with the black skin of the Moors |

Corippus, Iohannis 6.29‑98. |

Pagan |

Worship Gurzil and Jupiter-Ammon |

Corippus, Iohannis 6.145‑188, 3.82‑155, 1.282‑1.322 |

Table shows a selection of negative stereotypical traits assigned in Byzantine literature to the ‘Moors’, after Barreveld 2020.

Romans and Moors

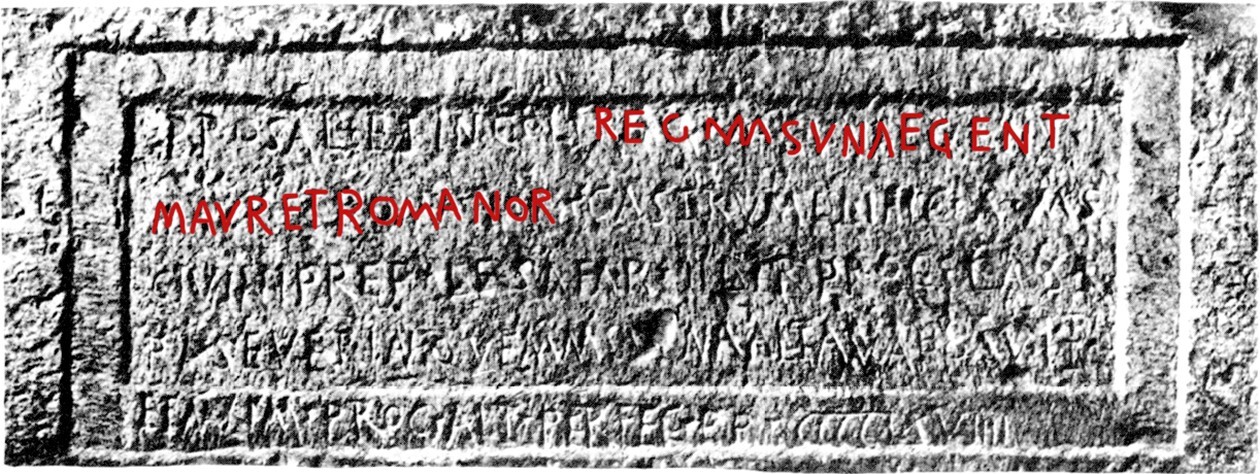

The historical reality was much more complicated. Racist stereotypes were conveniently used to differentiate the Moors when it suited Corippus and Procopius. At the same time we also find Moorish chieftains bravely fighting alongside Byzantine armies and participating in Roman culture. As one example, I can name the Berber king of Masuna, in whose honour a Latin inscription was raised in Altava (near modern Tlemcen, Algeria) in 508:

Pro sal(ute) et incol(umitate) reg(is) Masunae gent(ium) Maor(orum) et Romanor(um).

For the wellbeing of Masuna, king of the Moorish and Roman people.

Inscription praising Masuna as king of both Romans and Moors (highlighted in red by me). Source: Corpus inscriptionum Latinarum 8:9835.

Clearly, Moors and Romans could, and often did, live peacefully side-by-side. Like in the modern world, ethnicity and race in the post-Roman and Byzantine world were complex, three-dimensional issues that deserve serious study by today’s students of the past. There is still much to be written about the history of medieval racism.

Literature list

Barreveld, J., ‘Reflections on an Environmental History of Resistance: State Space and Shatter Zones in Late Antique North Africa’, Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 50 (2020) 153-165.

Isaac, Benjamin. ‘Proto-Racism in Graeco-Roman Antiquity.’ World Archaeology 38.1 (2006): 32–47.

Shea, G.W. The Iohannis or De Bellis Libycis of Flavius Cresconius Corippus (New York 1998).

Shelley, P. Haley, ‘Be Not Afraid of the Dark: Critical Race Theory and Classical Studies’, in: L. Nasrallah and E.S. Fiorenza ed., Prejudice and Christian Beginnings: Investigating Race, Gender, and Ethnicity in Early Christian Studies (Minneapolis 2009) 27-49.

© Jip Barreveld and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jip Barreveld and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.