How do you say "wrinkled" or "gap-toothed" in medieval French?

This blog post challenges the idea that French as a second language had predominantly elite connotations in the pre-modern period.

In the sixteenth century, it was perhaps not so unusual for a boy to say to his parents: “I will never call you hardfavoured, wrinkled, neither toothgaper!" Yet when all involved are English and living in England, why would he say it in French?

The traditional model

The French language has had a significant presence in England and the Low Countries for over a thousand years. According to traditional linguistic models of these regions, in pre-modern times it was typically the preserve of the "elite", and served prestigious judiciary, political, administrative and commercial functions.

Within the context of pre-modern England, the Norman Conquest of 1066 traditionally marks the "arrival" of the French language. In traditional models, French has often been characterised as a language imposed from the top down by the "foreign" rulers who arrived at the time of the Conquest. It is often said that outside the highest levels of aristocracy and the monasteries, and beyond the most international spheres of trade, the prestigious French language was barely spoken.

Similarly, it was once held that in large parts of the Dutch-speaking Low Countries, French was the language of the aristocrats who ruled these territories throughout the Middle Ages. Historians often describe French as the language of those who wished to climb the social ladder in the early modern Low Countries There is some truth to this traditional approach; French was employed, in this period, among the higher ranks of society and was an official language of the government. But of course, in the southern parts of the Low Countries, French was the vernacular. It was therefore understood that it was spoken by those in the north who traded or interacted with their Francophone compatriots in the south, or with other foreign traders.

Household French for the "commoners"

However, more recent studies (see for example Gallagher (2019) and Critten (2019)) paint a far more nuanced portrait of the francophone populace in England and the Low Countries. A close examination of key sources suggests that despite its elite origins in the areas under investigation, French came to be perceived not merely as a foreign language imposed from the top down, but as an important language for personal and domestic communications within two broadly multilingual societies. Our own research supports this idea.

The personal and domestic uses of French can be found in language manuals that were popular in the medieval and early modern periods throughout England and the Low Countries. The manuals feature practical dialogues whose contexts are primarily commercial (markets, trade, menders) or travel-related (inns, asking directions, small talk with travellers).

Surprisingly, examples of distinctly household French appear regularly in these manuals, in, for example, conversations between masters and servants and family members. Given the highly pragmatic nature of these manuals, the presence of French in these conversations speaks to the powerful role of French as an "internal" or domestic language for the English and the Dutch.

We will now present just a few charming examples of dialogues that challenge the notion that French was a purely elite and foreign language in these regions.

The Low Countries

In the Low Countries, Le Livre des mestiers (c. 1349), or De Bouc van den ambachten, is regarded as a seminal work amongst French learning manuals. It contains a combination of dialogues and word lists, which are classified in different categories, such as “De le [sic] maison” (“Vanden huus”) and “Des grans singneurs” (“Groote heeren”). In one less specific thematic category (“Il nous convient parler de pluiseurs autres coses”) we can find an example of household French in the Low Countries. The setting is a domestic conversation between two people, most likely a superior and his female servant:

‘Margot, preng de l'argent, |

‘Grielekin, nem ghelt, |

[Il nous convient parler de pluiseurs autres coses, p. 11]

The superior makes a request in French to the maid Margot, asking her to buy meat at the butchers'. The maid replies in French, asking for a specification of the request:

- Sire, quelle char volés [vous] |

- Heere, wat vleesche wildi |

[Il nous convient parler de pluiseurs autres coses; pp. 11-12]

Since this highly pragmatic conversation between a superior and a servant takes place in French, the dialogue suggests that the French language wasn’t used by the upper classes alone. We can think of multiple possible situations in which servants or other people from the lower classes would need to learn French. One possibility is that a Francophone superior would ask his servants to speak French during their work. In this case, the cited language manual could help them to learn, practise and improve their French. However, the opposite is also possible: a Dutch superior might employ French speaking servants and, thus, needs to learn or improve his/her own French. In our example, it does not become clear which of the two situations applies: we can’t be sure to whom the author intended to address his manual. Either way, both situations challenge the idea that French was only spoken by the elite and by traders in the Low Countries.

A few decades later, we find a very similar dialogue in the Gesprächsbüchlein romanisch & flämisch (c. 1360/70). Despite some minor differences – ‘Margot’ is now named ‘Margriet’ and the superior is now a lady – the two conversations are strikingly similar, and there is likely a direct link between the two.

‘Margriet, ou es tu?

- Dame, que vous plaist?

- Vien cha tost.

- Volentiers, dame.

- Prent de l'argent

et va au maisiel,

ou as maisiaus,

pour del char.

- Quelle char

volleis vous

que je achate?

- Tu achatras

de toutez manirez,

car nous avons

moult de ostes:

char de porc,

char de bakon, (…)

[Des chars; p. 17]

In this example, the details of the conversation are clearer to the reader than they are in the previous example. We know that the servant, Margriet, is talking to her female superior (“Dame”). Also, it is not the servant but the superior who lists the various types of meat in this conversation. Most importantly, the conversation is written in French, implying a need for the reader to learn this pragmatic vocabulary in the French language.

England

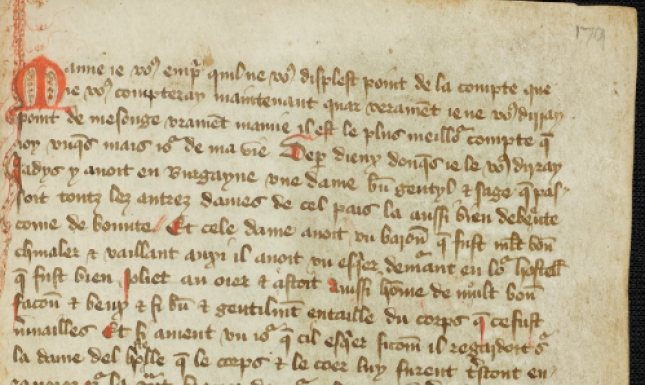

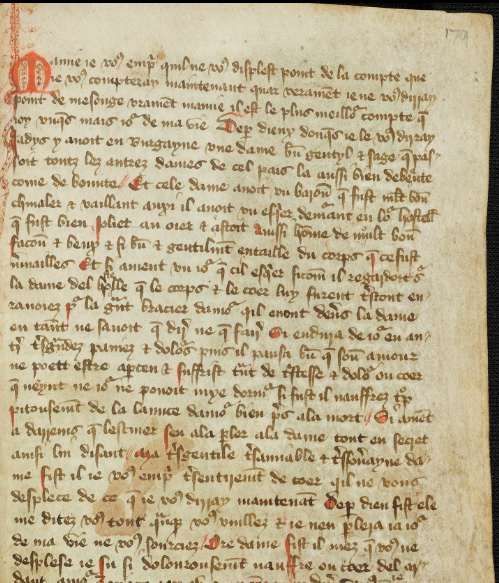

Clear parallels can be found in strikingly similar English manuals. A 1396 Manière de langage teaches how to communicate with a squire in French (Fig. 2). In one roleplay scenario, a master who is preparing for a journey to Paris learns how to ask a squire, Janyn, to prepare the horses:

Et primerment le seignour parlera a son vadlet devant son aler ainsi : [...]

- Va, mesnes mez chivalx a forges pur ferr[er], s'il en est meistre, et qu'ils en eient de bons ferres et fortz et bien forgez.

[4.1 Les préparatifs de voyage, p. 6]

When the master asks if the squire has completed the task, the manual anticipates the various ways in which the squire might respond in the affirmative (ignoring the possibility that the squire might not have completed the task!); three options are given for his response:

Oil, vraiment, mon seignour. Ou si: Oil, mon seignour, tresbien a point. Ou si: Oil sir, a vostre congé, certez je l'ay fait.

Janyn, whose name is distinctly French (Redmans 2004), is not restricted to a simple "yes, sir". Rather, three separate and distinctly colloquial possibilities are given for his reply. The unpredictability and comparative complexity of his responses seem to indicate that he is a competent Francophone.

In a later dialogue, the master asks a different domestic servant, Guillaume the valet, to prepare their meal. Guillaume lists more than thirty birds that are to be served at the second course! We can assume that this was a badly disguised excuse for teaching vocabulary:

dez chapons rostez et dez ouez, gaars, oyselons et auxi dez ans, anattz, madlardez de river, cignes, heirons, coverlons, grues, bitors, plovers, perdris, grivez, quailez, colombez, pugions, mavis, alloues, rassinolez, chardons, feusantz, videcok, chalaundres, verders, mosengez, musengez, begasez, blaretz, chardurolez, arundeez, oues rosers, cicoignez, pouns et de touz autrez oseux savage et domastez que l'en poet avoir, forspris lez oseux ravenous que ne sont pas tresbons a mangere com agas, kaves, cornails, corbels, frus, salamandrez, hulotz - vel: huetz -, soris chaux escoufles, sprevers, cercelers, faucons et esgles.

We can only conclude that this vocabulary, like the words for meat in the Dutch example above, was deemed useful for communicating with household staff. Perhaps such precise terms were needed for purposes related to hunting, preparing and keeping such birds. The sheer quantity and variety of animals listed indicate the potential need of such 'everyday' terminology.

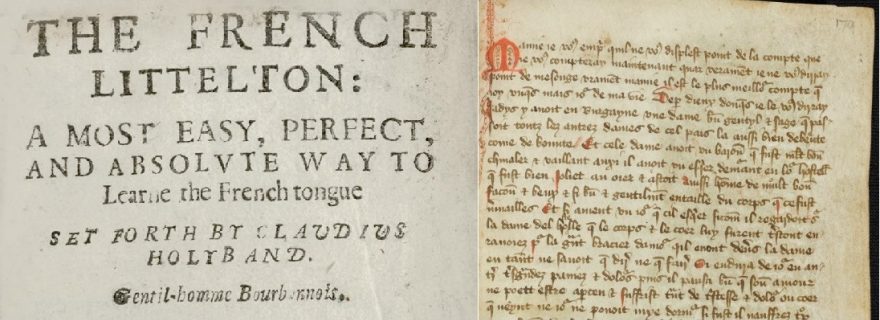

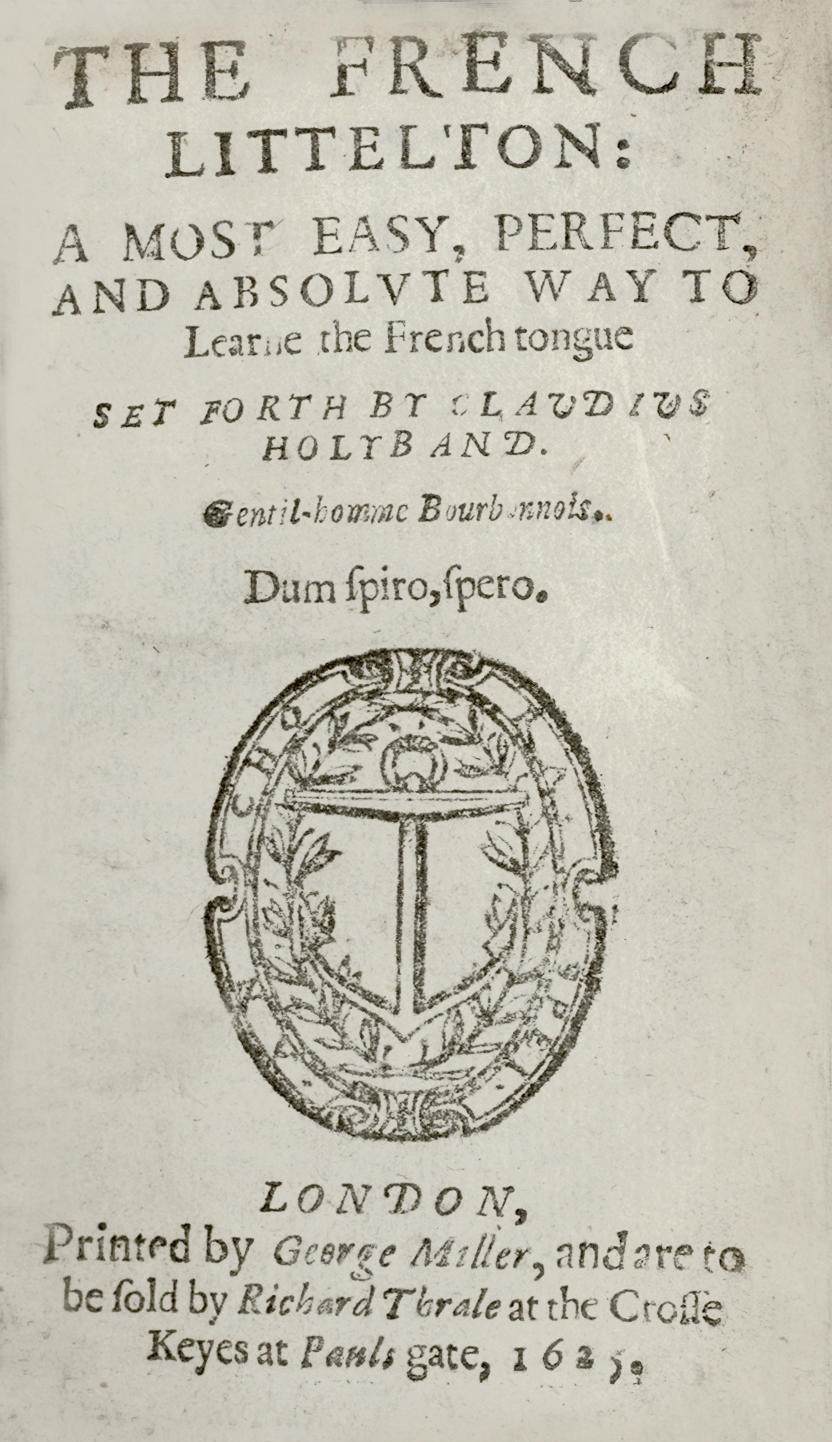

As late as 1566, a Huguenot refugee named Claudius Hollyband wrote the Frenche Littleton, a far more comprehensive educational French manual that enjoyed several reprints (Fig. 1). The dialogues he wrote for French instruction depict the language being spoken not just with household staff in England, but even within families.

In one such dialogue, a husband uses French to ask his wife whether she has prepared their son's breakfast and sent him to school. He then addresses his son—still in French—telling him to wake up, say his prayers and go, and warning that his schoolmaster will beat him. The son replies in French too, begging his father not to tell the schoolmaster of any misbehaviour, and promising not to call his parents hard-favoured, wrinkled or gap-toothed.

Fame, avez vous envoyé le garçon à leschole ? Lui avez vous baillé son desjuner ? certes vous en ferez un truant.

Il n'est pas encore levé, ny esveillé :

Marguerite, faites le lever, n'est-il pas temps ? il deburoit estre à N.

Hau Jaques levez vous, et allez à l'eschole : vous serez batu, car il est sept-heures passées : abillez vous vistement : mettez vous a genoux : dites voz prieres, puis vous aurez vostre desjuner demandez la benediction à vostre père : avez vous salué vostre père et vostre mère ? vous oubliez toutes bonnes manieres, et apprenez celles qu ne valent gueres.

Je vous prye ne le dites pas à mon maistre, et je ne vous apperlleray jamais laide, ridée, n'y édenté.

Wife have you send the boy to schoole? have you geven him his breakfast? truly you wil make a truant of him.

He is not yet up, neither awaked.

Marget, cause him to rise, is it not time? he should be already at N.

Hau James rise and go to schoole: you shal be beaten, for it is past seven: away your seife quickly: put you on your knees: say you prayers, then you shall have your breakefast : aske your fathers blessing: have you saluted you father and mother? you forget all good manners: and do learne those which be but littell worth.

I pray you do not tell it unto my Maister and I will never call you hardfavoured, wrinkled, neither tooth gaper.

[Hollyband, Claude. The French Littelton. Thomas Vautroullier dwelling in the blackefriers. 1566. Reprinted 1578, 1593, 1597, 1609, 1625, 1630. p.22.]

This dialogue demonstrates clearly that French was not thought to be restricted to the upper echelons of society in sixteenth century England. Its register, both familial and informal, indicates either that French really was spoken within "English" families that were far from aristocracy or that such families desired to learn truly ‘everyday’ French that was far from prestigious.

Conclusion

The dialogues given as examples above, all taken from language manuals ranging from c. 1349 to 1566, are evidence for domestic and familial French in England and the Low-Countries during the period. A close examination of these language manuals sheds light on the presence of the French language within homes. If scenarios featuring such informal conversations within the home (whether they be with household staff or between family members alone) are intermingled with other more internationally and commercially minded dialogues, it seems likely that French wasn't just a language useful for exchange with "foreigners" and aristocrats in the pre-modern Low Countries and England. In these areas, the French language, far from being the preserve of the rich and powerful, of the traders and travellers, was another vernacular.

Works Cited

- Unknown author. Le Livre des Mestiers (…). Original c. 1349 lost, transcription second half of the 14th century. Modern edition by Jan Gessler, 1931. Available online.

- Unknown author. Gesprächsbüchlein romanisch & flämisch. Original c. 1365 lost, transcription c. 1420. Modern edition by Jan Gessler, 1931. Available online.

- Critten, Rory G. ‘The Manières de langage as Evidence for the Use of Spoken French within Fifteenth Century England’. Forum for modern language studies, 2019-04-01, Vol.55 (2), p.121-137.

- Gallagher, John. Learning Languages in Early Modern England. Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Hollyband, Claude. The French Littelton. Thomas Vautroullier dwelling in the blackefriers. 1566. [reprinted 1578, 1593, 1597, 1609, 1625, 1630].

- Kristol, Andres Max. Manières De Langage, (1396, 1399, 1415). Anglo-Norman Text Society, 1995.

- Redmonds, George. Christian Names in Local and Family History. Dundurn, 2004.

© Myrthe Galle, Tanya Hart and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Myrthe Galle, Tanya Hart and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.