How to be a saint: A medieval guide to sanctity

Gregory the Great's 6th-century Dialogi is full of tips for a life of sanctity....

In a time without comic strips and superheroes, models of behaviour and rules of conduct were sought in the Bible. However, as time and distance separated humanity from those unreachable sanctified figures, there was a need for contemporary exemplars of sanctity.

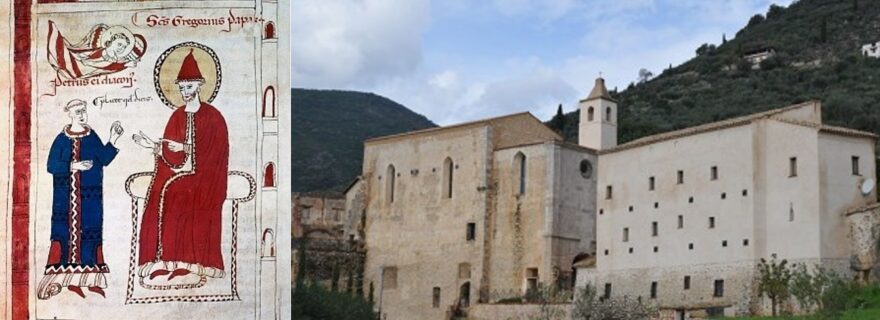

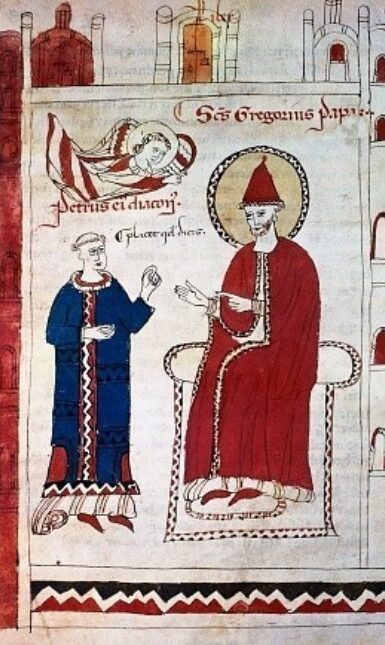

The request for a story (in a way that is common to many traditions, including the Iliad and A Thousand and One Nights) opens the first book of the Dialogi, a text by Gregory the Great narrating the lives of more than 100 italic saints in four books and written at the end of the 6th century. Gregory's narratives are presented in the form of a dialogue between himself and his deacon Peter, with Peter asking the questions the reader would have asked and Gregory answering with wisdom and clarity (like a Sherlock and Watson avant la lettre!).

Gregory the Great, not only the Pope but also the first Pope of the State of the Church, found himself amidst turbulent times, facing barbaric invasions from the Goths, the Longobards, and the Vandals. The invasions, past and present, left a very weak ecclesiastical structure and even weaker political structures: the cities were nearly abandoned, and society moved to the countryside. Far from the cities, Christianity lost its urban outlook and needed to find a way to survive in a simpler way.

This is the scenario portrayed by Gregory, who turned to the lives of contemporary saints to demonstrate that, even during these trying times, sanctity remained achievable with faith and Christian virtues.

The Rules of Sanctity

Gregory’s saints include martyrs, miracle workers and, above all, exemplars of unwavering faith in the Divine. Gregory showcases how these saints surmounted adversities, battled demons, and astounded barbarians. Within their stories lies the essence of sanctity, distilled into three guiding principles: imitation of the life of Christ; working miracles during one’s life; and the performance of miracles after their death. Saint Benedict, to whose life is dedicated an entire book (book II), serves as the best example of sanctity. Yet, nearly every saint's story follows the same pattern:

- sources of the story;

- a glimpse into their life with one or two defining episodes;

- miracles they performed posthumously;

- explanation of similar miracles performed by the biblical figures, including Christ himself.

To the modern eye, these miracles appear as some sort of magic and are hardly believable. This has led some scholars (like Francis Clarke) to question the attribution of the text to Gregory. However, Pope Gregory the Great held a steadfast belief in the power of miracles as tangible demonstrations of God's divine might. It was through these miracles that Gregory sought to reinforce the doctrine of the Catholic Church, thereby countering the persistence of pagan beliefs in 5th-century Italy.

Nevertheless, what sets Gregory's portrayal of saints apart from a purely miraculous perspective is his emphasis on inner sanctity and virtue. For Gregory, the real measure of a saint's worth lies not in the miraculous signs, but in the purity of their character and the embodiment of Christian virtues; the miracles become the representation of inner sanctity, that is achievable even by commoners. In this way, Gregory demonstrates that being a good Christian and being a good person are very close, if not the same thing. He gives rules of conduct not only to religious communities, but also to the inhabitants of the cities and the countryside, who were struggling due to the absence of a real political power to help them. Gregory provides comfort and hope, proving that, as long as they showed pious behaviour, they would be rewarded by God.

A Sanctity Trilogy: The Fondi's Abbey Adventures

The first three stories of the Dialogi showcase the most important virtues a good Christian should embody. The lives of Honoratus, Libertinus, and the hortolanus are built as a trilogy, each portraying a unique path to sainthood, guided by faith and divine providence.

Honoratus

The first life narrated by Gregory is the one of Honoratus, who was the slave (colonus) of an Italian landowner. Since his youth, he practiced abstinence (refraining from indulging in enjoyable but not inherently sinful foods like meat) which often earned him mockery from those who could not understand his dedication. One day, during a feast on a mountain, where meat was the sole offering, Honoratus found himself without food, subjecting him to further ridicule. However, in a stunning display of divine intervention, a servant arrived with a bucket of water from a nearby stream, and inside there was a fish! During the Middle Ages, fish was not considered a pleasurable food, and thus eating it did not break Honoratus' abstinence. With this unexpected provision, he had enough sustenance for the entire day and was no longer subjected to mockery.

In this first part of the story, we can detect some interesting elements: the first ones are Honoratus' abstinence and meekness. The second interesting element is the fish, which of course brings to mind Christ and the miracle of the multiplication of loaves and fishes. With this symbolism, Gregory demonstrates that those two virtues bring one closer to Christ.

Moreover, thanks to his virtuous life, Honoratus was freed from his servitude. He was grateful to God and established the monastery of Fondi, where he was the example of a good and righteous life. One day, a massive rock fell from the mountain behind the abbey and threatened to destroy the newly founded monastery. However, Honoratus managed to halt the rock’s descent by asking God to intervene. Thus, he proved that faith and prayer could exert great power over nature.

With this medieval version of Indiana Jones, Gregory addressed some of the concerns of his audience, who were battling daily with epidemics, catastrophes, flooding, and famines. He assures them that the answer is always in God and that prayer would save them against the threats of nature.

Another way to reassure his audience is to give the information that Honoratus did not have a master, which was strange for the hierarchal system of the Church. Instead, Honoratus was full of the Holy Spirit and that was enough since he performed miracles and carried himself with humility, the two distinctive signs of sanctity. Gregory corroborates this thesis by drawing parallels with St. Paul and Moses, neither of whom had conventional masters, but were guided by their connection with the Divine. In this way, the Pope tried to justify the fact that, during challenging times, faith in God transcended the need for a conventional hierarchy. Thus, he reveals that the essence of sainthood emanates from within and is driven by the connection to the Divine.

Libertinus

In the Fondi trilogy, the second 'hero' is Libertinus, a devoted disciple of Honoratus. This chapter marks the appearance of the barbarians, introducing the real enemy of the Dialogi and a new dimension of challenges to test the saint's faith and character.

When the general of the Goths, Darida, arrived at the monastery, he unjustly seized Libertinus' horse. Libertinus did not react with anger, but with remarkable humility and meekness, showcasing two distinct traits of Gregory's saints: they do not wield their divine strength against the barbarians, nor do they seek vengeance. Instead, they exemplify virtuous behaviour and they are ultimately rewarded for this. As a matter of fact, after being robbed of his horse, Libertinus praises God. By contrast, the barbarians face an unexpected consequence of their actions as they attempted to continue their journey, but their own steeds refused to budge. As a consequence, the Goths were forced to go back to the saint recognising Libertinus' divine connection. As soon as they returned the stolen horse to its rightful owner, their horses started moving again.

The narrative unfolds further as the second barbarian of the story, Bucellinus, tried to loot the monastery. Once again, Libertinus' faith and prayers resulted in a miraculous outcome: the barbarians were struck blind and were unable to carry out their nefarious intentions.

These two episodes provide some guidance on how to deal with barbarian invaders, teaching the commoners and the monks not to engage in battle with them, but to have faith in God who will reward and provide for them.

As the story continues, we find Libertinus traveling to Ravenna. On the way, he was approached by a desperate woman pleading for the resurrection of her child. Demonstrating his modesty, he hesitated at first, but then he was moved by the piety of the woman and used Honoratus’ holy socks that he had always with him to resurrect the child. This segment introduces two more virtues: modesty and piety. With them the idea of relics (brandeium in this case), as the closest way to invoke divine intervention. Moreover, in this case, Gregory explicates the parallel with a biblical figure, saying that Eliseus performed a similar miracle with his master's cloak.

Lastly, Libertinus' meekness and submission are proved once again even when faced with mistreatment. When his abbot hit him, he refrained from retaliation and, instead, followed Christ's example and turned the other cheek.

In Gregory’s description of Libertinus’s life, we again find a profound and timeless lesson for Italy's monks and religious communities. The portrayal of humble and meek behaviour, even in the face of abuse of power from superiors, reflects the challenges and realities of monastic life at the time of Gregory. The Pope's teachings call upon the monks to find strength and reward in their faith in God rather than resorting to confrontation or rebellion. Gregory emphasizes that true sanctity lies not in seeking power or retaliation but in surrendering oneself to the divine will and exemplifying virtuous conduct.

The hortolanus monk

The story of the nameless third saint of Fondi's abbey is told by a close friend of Gregory, named Felix, who describes the anonymous saint as the abbey's hortolanus. When this nameless gardener noticed the disappearance of vegetables from the hortus, he decided to instruct a snake to guard the entrance of it. When the vegetable thief returned, he encountered the snake. Scared and feeling threatened, he tried to run away but fell into a bush, hanging upside down from his feet. When the gardening monk came back to the garden, he drove the snake away, recognizing the thief's desperation and showing great compassion and forgiveness. Since then, the hortolanus offered the thief food whenever he needed it, thus redirecting him away from committing a sin.

With this story, Gregory addresses the religious communities, conveying a message of compassion for the poor people, encouraging to help them, not only to exercise a Christian virtue but also to offer the sinner an opportunity for redemption.

Not only does the snake represent the devil in Christian symbolism, but also the story is set in a garden just like the story of Adam and Eve is set in the Eden. The depiction of the snake as powerless and subservient reinforces the belief in the supremacy of goodness and virtue. The snake here is not the vehicle of temptation and sin. On the contrary, its action becomes the means to stop the cycle of wrongdoing. In this way, the story is a powerful allegory proving that virtue and saintly life can win against the most ancient forms of evil.

The pattern of these stories resembles the one of Esopo and Fedro's tales, where a simple story carries a profound morale and a powerful teaching. Indeed, the Fondi's trilogy, just like the whole content of the Dialogi, presents a powerful set of rules of conduct for monks and religious communities, as well as a valuable tool for the clergy in their homilies, since these stories are intended as an instrument of evangelization.

Reception of the Dialogi in Anglo-Saxon England

It is known that King Alfred the Great (d. 899) was a big fan of Pope Gregory and the four books of the Dialogi must have struck a particular chord in him. He asked his loyal friend, Bishop Wærferth, to translate them into Old English sometime before he started his project of cultural reformation and translations. This translation served as a conduit, introducing England to the profound models of sanctity and resilience depicted by Gregory, establishing a remarkable continuity between 6th-century Italy and 9th-century England.

Both Alfred and Gregory's times shared striking similarities, as they both faced the challenges of battling against pagans. Gregory's portrayal of the pagans as savages was surely beneficial to Alfred's propaganda effort to highlight the superiority of Christianity over the paganism that typified the Viking invaders that terrorized English shores. Just like Christianity won with the baptism of the Viking commander Guthrum after Alfred’s victory at the Battle of Edington (878), Gregory’s accounts of barbarians being amazed and frightened by the saints' miracles and moral force underscored the triumph of Christianity.

Gregory's models of community reconstruction and endurance in times of political and ecclesiastical weakness continued to resonate in England. During the 11th-century Benedictine Reform, the first two books of the Old English Dialogi were revised in MS Hatton 76 (ff. 1-56) to bring the language up-to-date with contemporaneous Benedictine vocabulary. This comprehensive revision exemplifies how Gregory's teachings continued to be treasured and utilised to inspire and guide religious communities over the centuries. Similarly, the Dialogi were a great source for Ælfric, the 11th-century abbot of Eynsham and prolific writer, who understood their evangelical power and used them in his homilies.

As such, Gregory's manual to sanctity was appreciated throughout the early Middle Ages, leaving a profound impact on communities and individuals alike.

Selection of relevant literature:

- Boesch Gajano, Sofia, Gregorio Magno: alle origini del Medioevo (Viella 2011).

- Clark, Francis, The Authenticity of Gregorian Dialogues, A Reopening of the Question? in Grégoire le Grand. Chantilly, Centre culturel Les Fontaines, 15-19 septembre 1982 (Colloques internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifiques), pp. 429-443.

- Cracco, Giorgio, Ascesa e ruolo dei "Viri Dei" nell'Italia di Gregorio Magno, in Hagiographie, cultures et sociétés, IV-XII siècles (Actes du Colloque organisé à Nanterre et à Paris, 2-5 mai 1979), pp. 283-297.

- Dekker, Kees, King Alfred’s Translation of Gregory’s Dialogi: Tales for the Unlearned, in Rome and the North. The Early Reception of Gregory the Great in Germanic, ed. by R. H. Bremmer, K. Dekker, D. F. Johnson (Paris-Leuven-Sterling 2001), pp. 29-50.

- Dendle, Peter, Satan unbound: The devil in Old English narrative literature (Toronto 2001).

- Hecht, Hans (hrsg. von), Bischofs Wærferth von Worcester Übersetzung der Dialoge Gregors des Großen über das Leben und die Wundertaten Italienischer Väter und über die Unsterblichkeit der Seelen (Leipzig 1900); 2. Abteilung: Einleitung (Leipzig, 1907).

- Johnson, David F., Why Ditch the Dialogues, in Source of Wisdom, ed. by Ch. D. Wright, F. Biggs, Th. N. Hall (Toronto 2007), pp. 201-216.

- Kingston, Christine, "Taking the Devil at his Word: The Devil and Language in the Dialogues of Gregory the Great" in «The Journal of Ecclesiastical History» 67(4), (2016), pp. 705-720.

- McCready, William D., Signs of Sanctity. Miracles in the Thought of Gregory the Great (Toronto 1989).

- Pricoco, Salvatore, La chiesa nell’Italia longobarda in Storia del cristianesimo: L’antichità (vol.1), a cura di G. Filoramo, D. Menozzi (Roma 2002).

- Simonetti, Manlio, Pricoco, Salvatore (a c. di), Gregorio Magno: Storie di Santi e di diavoli, 2 voll. (Milano 2005).