John of Pamele’s Illustrated Rent Book

John of Pamele’s illustrated ‘Vieil Rentier’ is one of the few surviving secular rent books from before 1300. Its richly illustrated pages show John of Pamele as a commited landlord managing his far-flung properties.

While numerous rent books and cartularies of before 1300 survive from religious institutions, their secular counterparts are rare. Even so, John of Pamele, Lord of Oudenaarde from 1242 until his death in 1293/94, possessed one of each: a richly-illustrated cartulary made in 1261 (Lille, Archives départementales du Nord, B 1570) and a rent book known as the Vieil Rentier of Oudenaarde of c. 1275-76 (Brussels Royal Library Albert I, ms. 1175), which has colour-washed pen drawings. Although not unparalleled, the Oudenaarde Vieil Rentier is a unique manuscript and one wonders why it was made.

John of Pamele

At least since the eleventh century, Oudenaarde, a town along the Scheldt, the border river between the bishoprics of Tournai and Cambrai, and between French Flanders and Imperial Flanders (Rijks-Vlaanderen), was owned by the Lords of Pamele, high-ranking vassals of the Count of Flanders. By marrying well, they had substantially enlarged their family’s possessions, not only in Flanders but also in the counties of Hainault, Brabant, Namur, Holland and Champagne, and they also held land from the Lord of Mortagne, the Bishop of Laon and the King of France. Not surprisingly, John of Pamele’s Vieil Rentier was first of all intended as an in-depth survey of these possessions.

The book is organized by village, registering hamlets, houses, arable land, mills, fish ponds and so on, and lists who owed what to the Lord of Pamele. Unfortunately, twelve out of forty quires of John of Pamele’s rent book are reckoned to be missing, among them the first six. This accounts for the confused beginning of the manuscript and the many different hands responsible for the first 15 folios. The missing folios also explain why only two villages are discussed that are located north of the river Scheldt, in French Flanders, where John obviously owned a lot more property. It is only from fol. 16 onwards that the manuscript is better organized and has more substantial and illustrated entries.

The drawings

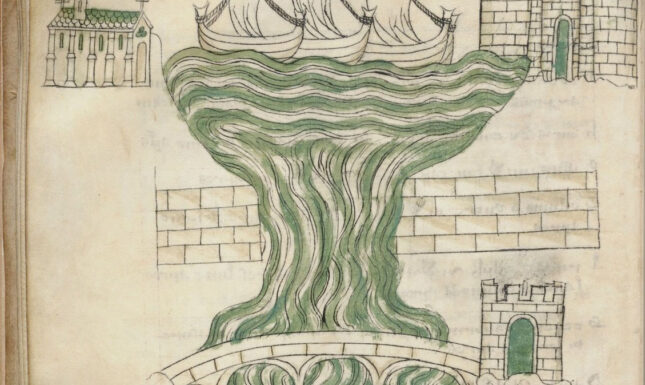

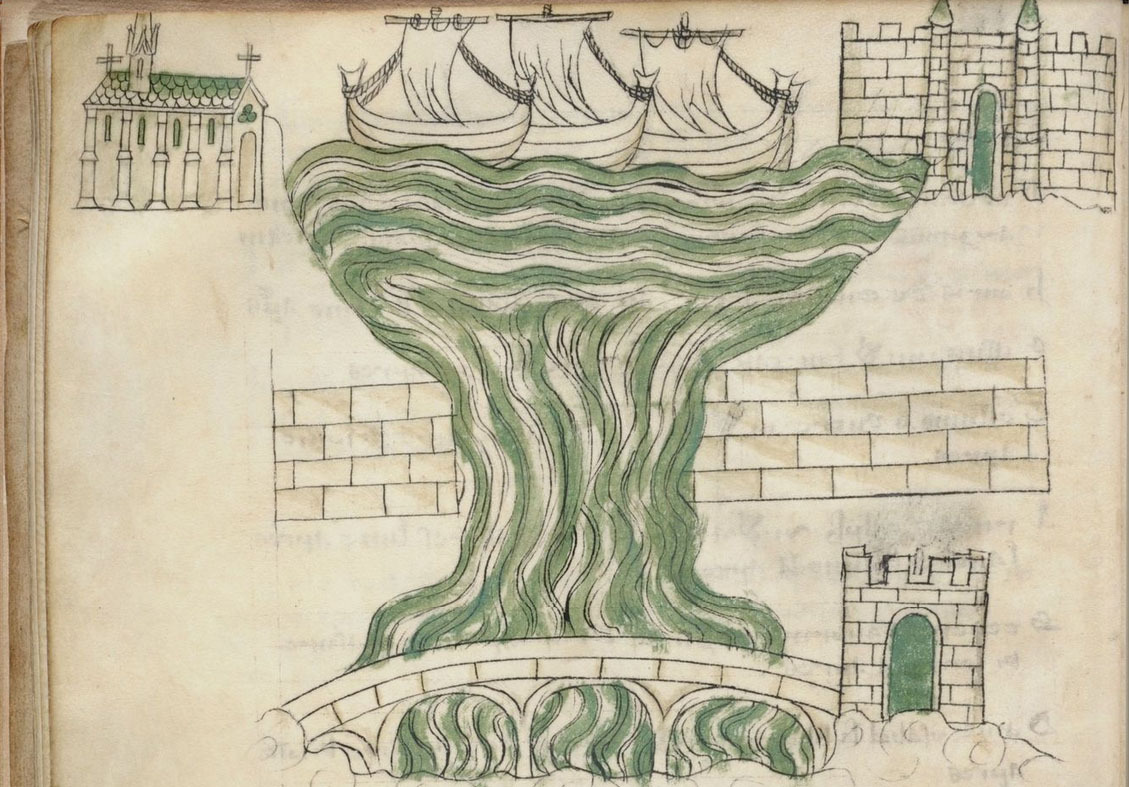

The majority of the drawings refer, in one way or another, to the major sources of income of John of Pamele. The most extensive picture in the book is of the lock in the Spei (plate 1). The fall of the river in its middle and upper sections was used to drive a series of watermills. The picture shows the Scheldt bridge, the stone lock, and three boats. On the south bank is the church of Our Lady of Pamele, the north bank shows a tower guarding the bridge and the castle of the Lords of Pamele.

The rents listed are those of the area named ‘Tussenbruggen’, between the bridges (i.e. the bridge between Pamele and Oudenaarde and the bridge between the city and the castle). While the income derived from the people living here was negligible, the river tolls, bridges and mills were highly lucrative. Images of a man with a cart and four horses, cattle, a forest, the lord and his men, moneylenders, the mayor and his sheriffs, as well as wind and water mills illustrate the economic and social activity in the area.

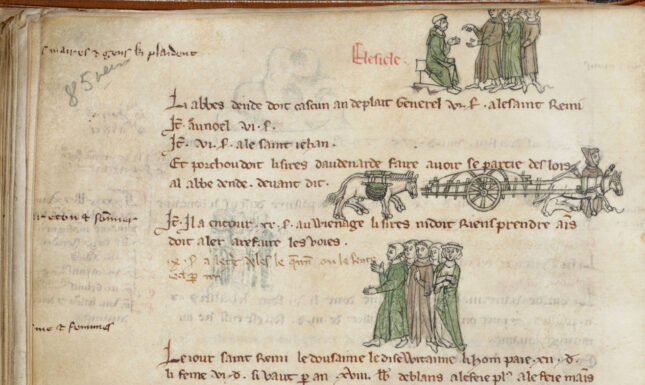

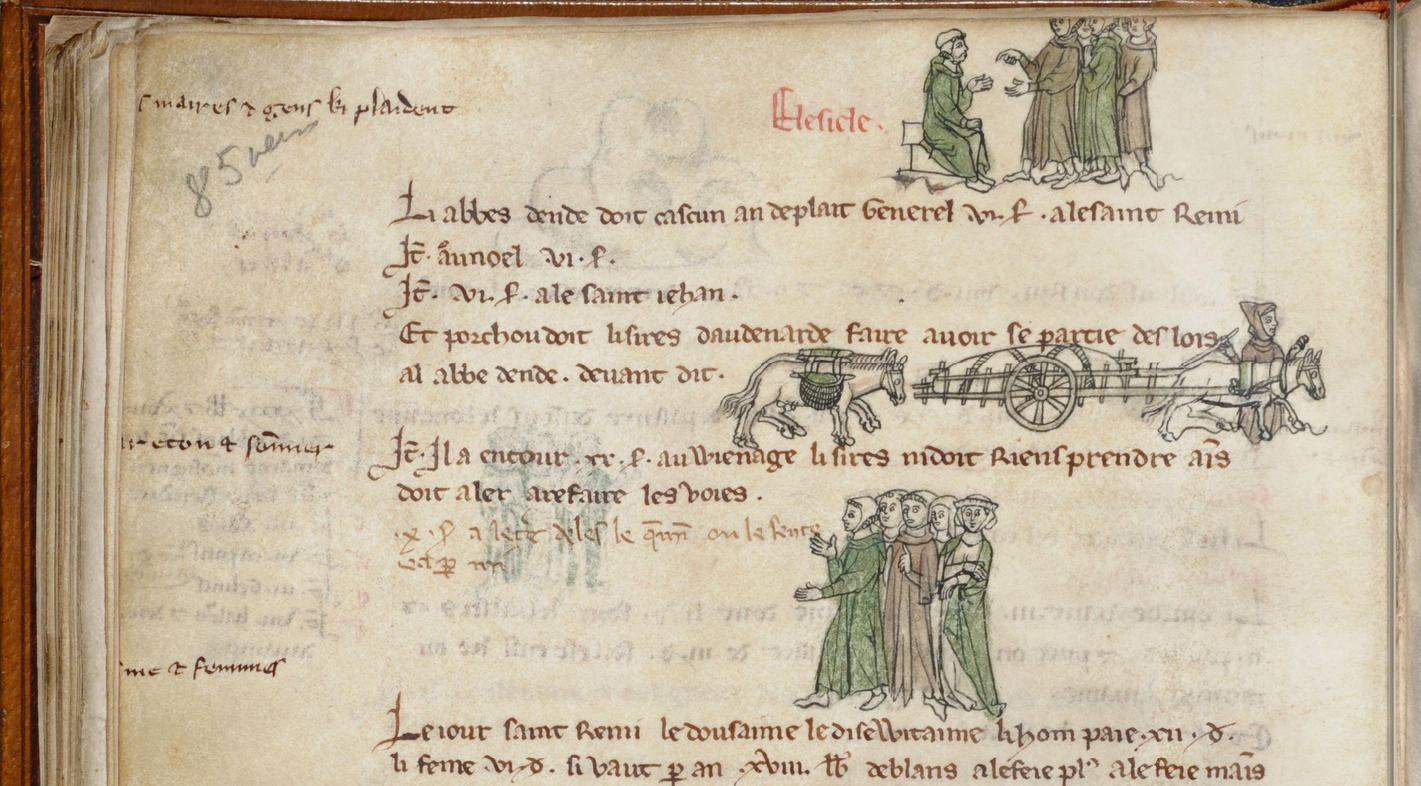

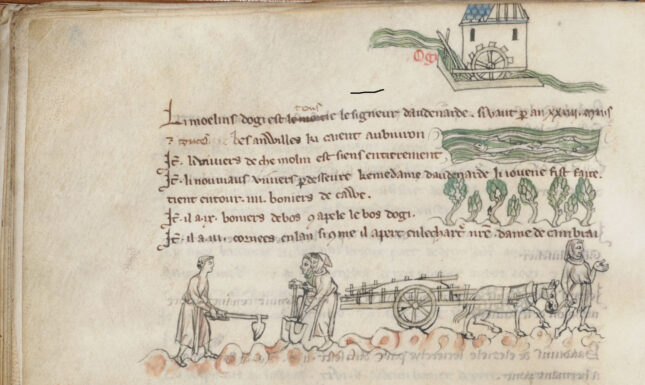

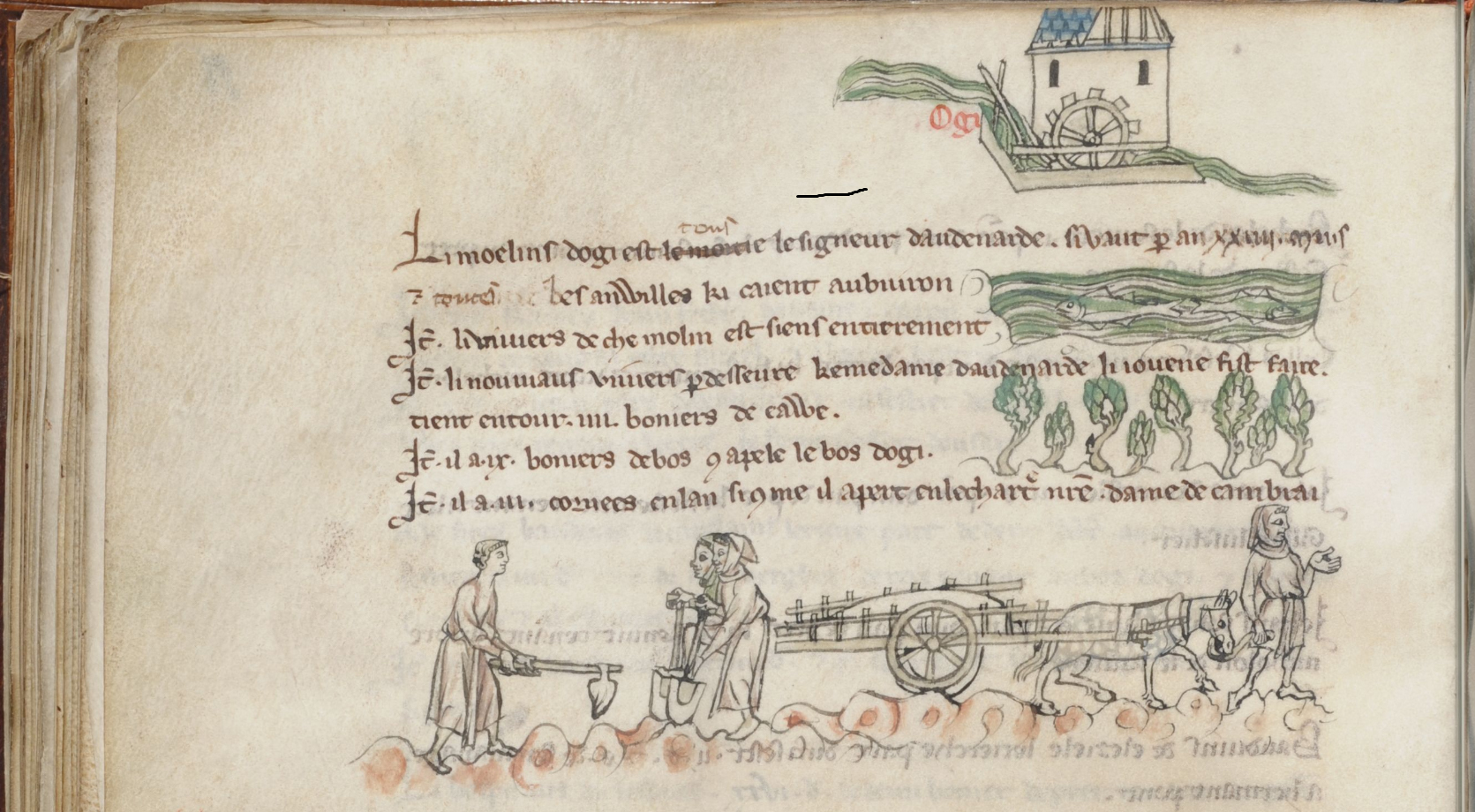

Markets were another major source of income. The one in Flobecq is represented by the market hall and a group of negotiating sellers and buyers. Other images include the tavern at Schorisse, the bustling village of Elzele, with all manner of villagers, vassals, a judge and defendants, a cart and horses and a liegeman (plate 2). For Ogy, there is a watermill, fish pond and wood, as well as three men working the land and another with a horse and cart. Isnières has people working the field and a man ploughing. The ‘Tuillerie’ is characterized by a pile of roof tiles, and the potteries at Vloesberg by a row of five red pots. While there is but one farm depicted in the manuscript, fish ponds, fountains and streams feature regularly (plate 3), as do fields, meadows, woodland and images of sheaves of grain.

Several drawings refer to payday. The figure of St John the Baptist, for instance, illustrates the beginning of the Tongre entry, with the adjacent text informing us that the rents at Tongre were to be paid on St John’s day. Some rents were due on St Rémi’s day and those are accompanied by the image of St Rémi baptising King Clovis.

In addition, quite a few of the drawings refer to boundaries and/or landmarks, such as the windmill at Ronse, the smithy at Nukerke, the chapel of Zulzeke on the boundary with Berchem, the Gibbet Hill, the swamp at Vloesberg, as well as bridges, rivers, way crosses, hermitages and chapels. Hills and castle mottes were also notable landscape features. Even trees could be landmarks, such as the poplar at Nukerke (Nueueglize) along the stream leading on to Ronse that marked the divide between the lands of the Lords of Oudenaarde and Wattripont, whose heraldic shields are shown in the margin. Heraldic shields were also used to indicate those lands and rents of which John of Pamele was a mere ‘shareholder’.

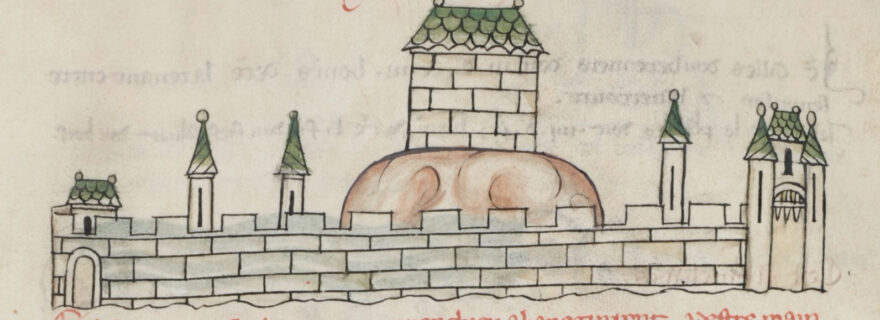

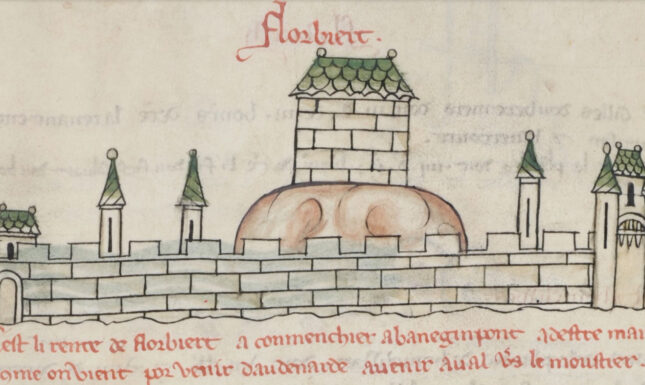

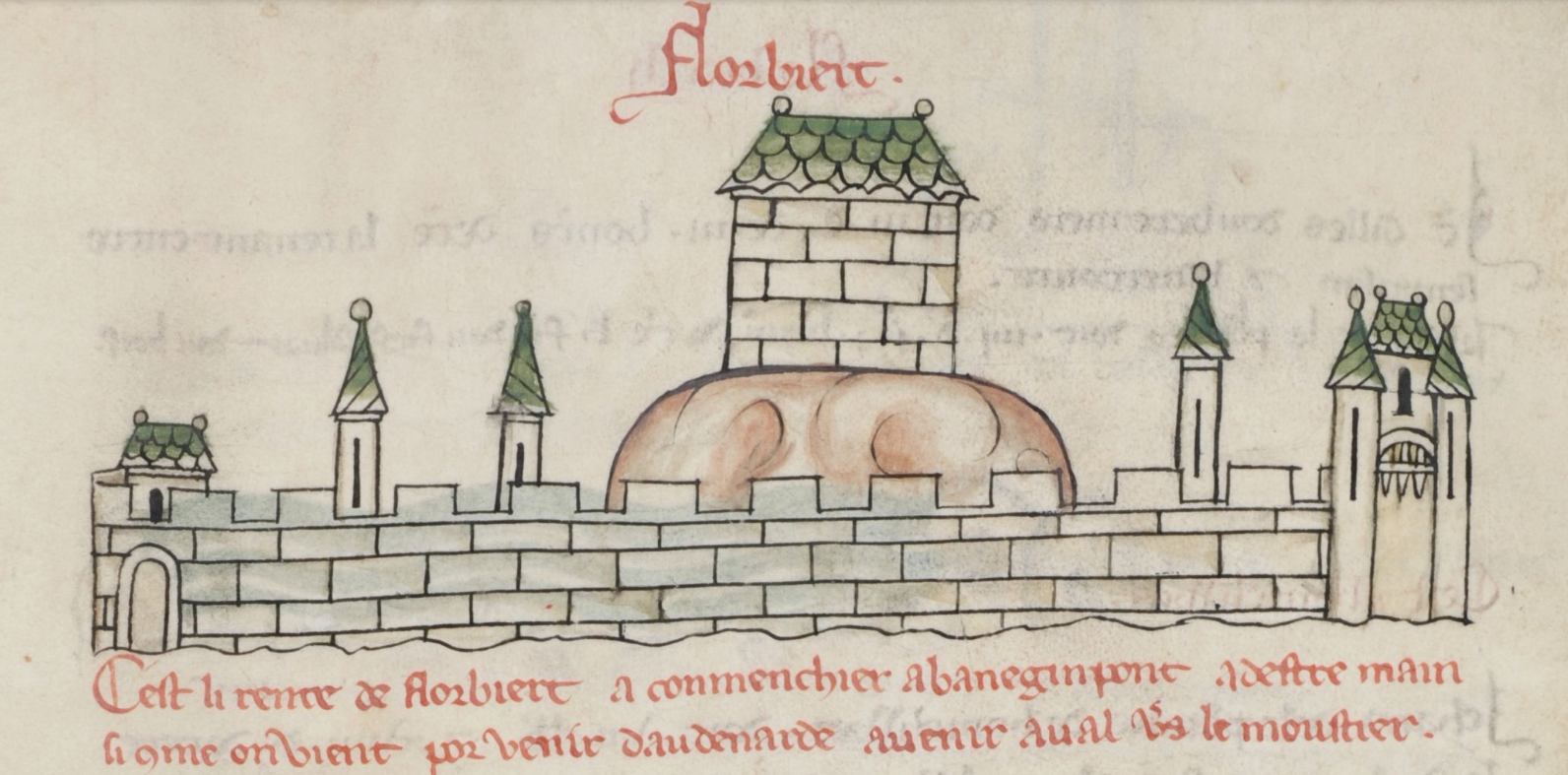

Several images in the manuscript are associated with the patronage of the Lords of Pamele, showing, for instance, the abbey of Ename of which the Lords of Pamele had held the under-advocacy since 1064. Moreover, John’s father Arnold, who had died in 1242, was buried there. Lessines is represented by its walls, turrets and several entrance gates, built by John’s father Arnold. Arnold’s wife Alix de Rozoy built the Hôpital de Notre-Dame à la Rose in Lessines, which is also illustrated, in her husband’s memory. As the Lords of Pamele were also Lords of Flobecq, the castle there features at the beginning of the Flobecq entry (plate 4). Behind the enceinte with its two entrance gates and three turrets a motte rises, surmounted by a stone tower.

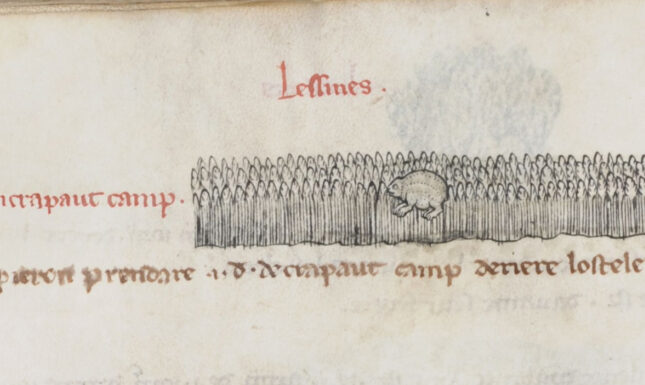

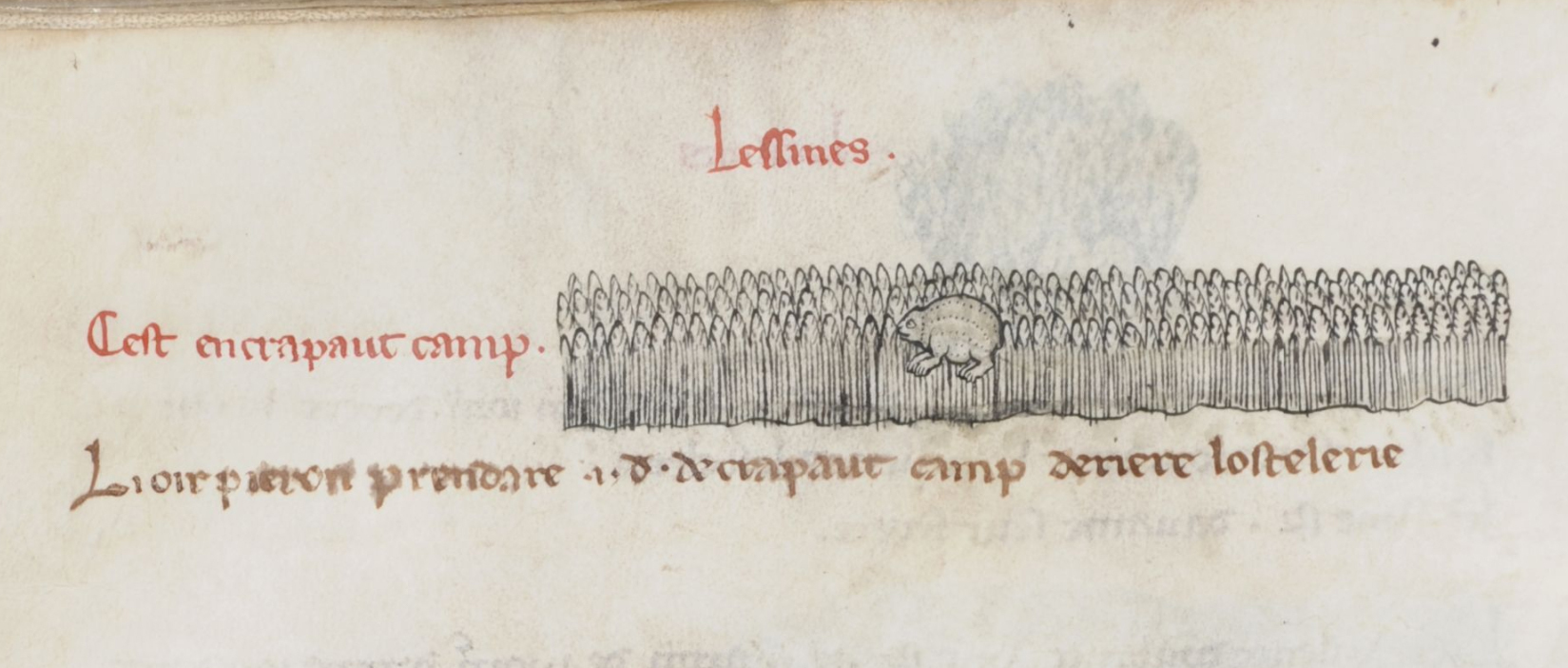

Some drawings have a rebus-like character, a case in point being the one illustrating Merelberg (blackbird hill), depicted as a blackbird on a hill, or Flamecamp at Flobecq, shown as a field with flames. The mention of the hamlet of XXX Espis at Ghoy is accompanied by a drawing of thirty stalks of grain; Ankerbroek by a stream with an anchor. A rock with three pots on top represents Potter’s Rock, while the forest of St Amand is shown as trees with a monk, and the Laureinsberg as a hill with St Lawrence being fried on a grill. Crapaut Camp becomes a field with a toad in it (plate 5).

On master Quentin

Being named in two other manuscripts by his hand, we know the identity of the man who conceived the Vieil Rentier. The oldest of these is the cartulary of the Lords of Picquigny (Somme region) (Paris, Archives Nationales, R1 672) that names master Quentin as the scribe on its title page. Begun in 1250, it was in all likelihood made by order of Mathilde de Crecques, the recently-widowed wife of Gerard III de Picquigny +1249). In 1250, she remarried none other than John of Pamele, who had just lost his first wife. Around 1261, Quentin made the aforementioned cartulary for him, followed by the Vieil Rentier. Another manuscript related to master Quentin is the Terrier de Cambrai, a rent book listing the privileges and income of the Bishop of Cambrai (Archives dept. Nord Lille ms 3 G 1208, Musée 342). It was probably made for Enguerrand II de Créquy, bishop of Cambrai from 1273 to 1285, whose shield is depicted in the manuscript. It has 317 folio’s with 160 small drawings that resemble those in the Vieil Rentier. What is more, the hand of another of the scribes who worked on the Vieil Rentier has also been recognized in this manuscript. Family connections probably explain how these two clerks came to be in the employ of the Bishop of Cambrai. Through his mother Idèle, bishop Enguerrand descended from the Picquigny family, Idèle being the sister of Mathilde’s first husband.

The purpose of the Vieil Rentier's imagery

Enguerrand had come into conflict with his canons about the revenues he was entitled to, a quarrel that may well have provided the incentive for having the manuscript made. This concurs with the general idea that cartularies and rent books usually appear in times of crisis and reform. What then was the context against which to set John of Pamele’s 1261 cartulary and 1275-76 rent book?

Apparently, from 1261 onwards John sensed trouble due to the fact that Margaret, Countess of Flanders and Hainault had married twice. Her first marriage to Burchard of Avesnes had been condemned by Pope Innocent II because not only had Burchard been destined for the church, he had even received orders. This is why Margaret left Burchard in 1222 and married William of Dampierre. In 1246, she named her son Guy of Dampierre as her sole heir, thus disinheriting the sons by her first marriage, which led to a feud between the Avesnes and Dampierres. The French King, asked to arbitrate, decided that Flanders was to go to Guy of Dampierre and Hainault to John of Avesnes. The possession of Imperial Flanders, the region where the Pameles held considerable territories, remained disputed, meaning that at some stage John of Pamele would be forced to choose sides. As most of his lands were situated in Hainault, John opted for Hainault. On Margaret’s death in 1280, this choice did indeed get him into trouble with Guy of Dampierre, the new Count of Flanders. The territory comprising Lessines, Vloesberg, Bois-des-Lessines, Elzele, Ogy, Papignies and Wodecq would in due course come to be known as the ‘Terre des Débats’, because of the continuous warfare there. It was against this background that John decided to get his administration in order.

Just by leaving through the Vieil Rentier one would get a sense of the landmarks of John of Pamele’s lands, the people living there, and the assets providing him with the means to uphold his castles, court and noble lifestyle. The images also brought home that law and order (burgomaster and sheriffs) reigned in John’s lands. It also showed that John and his family ensured the safety and health of their subjects and the church by erecting city walls, castles and hospitals, while also taking the infrastructure in hand (lock, bridges, roads). All in all, the book presents him as a committed landlord, an effective ruler and a good administrator in word and image.

Selected sources

The manuscript was first published by L. Verriest, Le polyptyque illustré dit 'Vieil Rentier' de messire Jehan de Pamele-Audenarde (vers 1275). Prolégomènes, Brussels 1950.

Jean-François Nieus, ‘Les quatre travaux de maître Quentin (… 1250-1276…): cartulaires de Picquigny et d’Audenarde, Vieil rentier d’Audenarde et Terrier l’évêque de Cambrai. Des écrits d’exception pour un clerc seigneurial hors normes’, Journal des savants 2012-1, 69-119.

https://opac.kbr.be/Library/di...

© Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.