Medieval Mushrooms

Was Jesus a mushroom? Just posing this question suggests the author visited one of Leiden’s smartshops before writing this post. Rest assured, the content is based on sober reading and explores theories on the role of mushrooms in medieval Christianity.

This post stems from my childhood fascination with mushrooms that was newly triggered by a recent publication of a book in Dutch on the role of mushrooms in the arts (Antoon Kuhlmann and Dominique Clement, Paddenstoelen in kunst, cultuur en natuur [Mushrooms in Art, Culture, and Nature] (Zeist: KNNV Uitgeverij, 2020). Growing up with Czech grandparents who had a ‘chata’ (a cabin to which luxuries such as a bathroom were added over time) at the edge of a wood, the love for searching for mushrooms was instilled from early on. Still, I find it one of the most relaxing and rewarding past times: the sight of a nice, plump porcini nestled in forest growth close to an oak is magical. Even now when going for a hike my eyes tend to skim the forest floor. When I come across something edible I cannot help myself and have to point out the mushroom’s culinary possibilities, even though I only take pictures of my best finds (Fig. 1).

When I heard one of the authors of the aforementioned book on Dutch national radio (NPO 1) mention medieval images of Adam and Eve with mushrooms instead of the familiar forbidden fruit, I was intrigued – much to the dismay of my partner, a fellow medievalist. Probably because the book was featured in a biology-oriented show (Vroege Vogels [Early birds]) the matter of mushrooms in medieval images was only discussed superficially and the interviewer accepted the possible role of mushrooms in Salvation History without much reservations.

I had never heard of Adam and Eve digesting mushrooms, and the item also made me think about the role of mushrooms in medieval Dutch literature: did mushrooms play a role, and if so, how did the medieval inhabitants of the Low Countries perceive them when they undoubtedly came across mushrooms each autumn?

Mushrooms and Toads in Middle Dutch

The latter issue was resolved rather quickly: my hunch that I had never comes across mushrooms in Middle Dutch literature was confirmed by a search in the Middle Dutch Dictionary (https://ivdnt.org/woordenboeken/middelnederlandsch-woordenboek/). The first time a variant of the current Dutch word for mushroom (‘paddenstoel’, cf. ‘toadstool’, the latter, however, is used for poisonous mushrooms only) was used appears to have been relatively late, in 1477. We find the word ‘paddenstoil’ in a dictionary of words translated from the vernacular of the region around Kleve, a German town close to Nijmegen and the current Dutch border, into Latin and vice versa. The vocabulary was complied by Gert van der Schueren († 1496), chronicler and secretary to the Duke of Kleve, and published in Cologne by the printer Arnold ter Hoernen on 31 May 1477 (Fig. 2). On folio C6r we find the following entry, which includes a number of vernacular alternatives: ‘Bulte, drieslyng, peddenstoil, peperlynck, swam – Fungus, boletus, voluus’ (Fig. 2).

The Etymological Dictionary of the Dutch Language (http://etymologiebank.ivdnt.org/trefwoord/paddenstoel) states that the choice for ‘pad’ (‘toad’) as the first part of the word is based on the ‘devilish’ reputation of that animal. No mushrooms figure, however, in works such as Der naturen bloeme, a Dutch recension of Thomas of Cantimpré’s Liber de natura rerum composed in the thirteenth century by Jacob van Maerlant, called the ‘father of all poets [who write] in Dutch’ (‘vader der Dietse dichtren algader’). The book discusses all nature’s phenomena, but alas, no mushrooms. It does feature a toad, described as venomous and horrible to see and touch. Moreover, the section on peoples that inhabit the peripheries of the Christian world features a nation whose women first bear a toad when giving birth to a child. This trait emphasizes their non-Christian and monstrous nature (Fig. 3).

The search for mushrooms in Middle Dutch texts is thus disappointing and yet intriguing at the same time. Did authors deliberately steer away from mushrooms because of their dubious reputation? Or were they simply of no interest to the authors and readers of the Dutch medieval vernacular? And how does this compare to other vernaculars?

An Alternative History of Salvation?

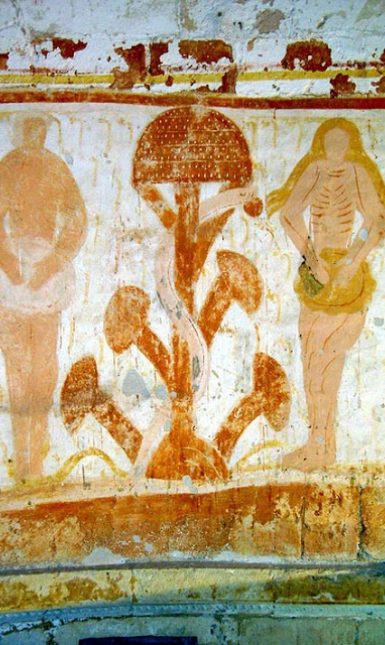

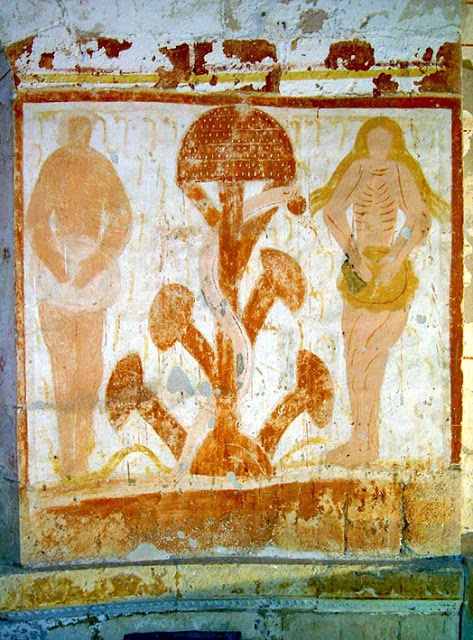

So what about the ‘Mushroom of the Knowledge of Good and Evil’? Central to this contentious theory is a fresco preserved at the Chapel of Plaincourault in Indre, Central France, and dated to the final decade of the thirteenth century (Fig. 4). In his 1970 study The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, John M. Allegro, a philologist and specialist of the Dead Sea Scrolls by trade, argued that this depiction of Adam and Eve had an Amanita muscaria mushroom – the well-known fly agaric – at its center. According to him, Christianity was based on a fertility cult and the Eden story a ‘mushroom-based mythology’. These roots were still acknowledged during the Middle Ages. The Times evaluated Allegro’s work as ‘a sensational lunatic theory’ in 1971 and the book ruined his reputation and career (discussed in Brown and Brown 2019, pp. 144-146).

Allegro’s thesis was fiercely combatted by R. Gordon Wasson, a banker turned ‘ethnomycologist’ – a student of the role of mushrooms or entheogenic (i.e. psychoactive) substances in religion – who had published a study two years previously, in 1968, and argued that the fly agaric played no role in medieval Christianity. Supported by the opinion of the influential art historian Erwin Panofsky, Wasson pointed out that the fly agaric in the mural was in fact a stylized pine tree, to which historians of Romanesque art refer as a ‘mushroom-tree’.

Recently the Wasson-Allegro controversy has been revisited by Jan Irvin (The Holy Mushroom, 2008; see Winkelman 2010) and John Rush, who in a book titled The Mushroom in Christian Art (2011) argues that Jesus can be viewed as a personification of the fly agaric. Book merchants nominated the latter study for the ‘Diagram Prize for Oddest Title of the Year’, together with titles such as Cooking with Poo and The Great Singapore Penis Panic, which gives an indication of the reception of the publication among the general public (Joseph Brean, ‘The joy of oddly titled books; Annual contest’, National Post, 25 February 2012). Allegro’s The Sacred Mushroom must have, at least initially, met with less skepticism: I was able to locate it at Leiden University Library, together with Wasson’s Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality (1968).

Renewed Interest

In 2019, another reassessment appeared in the Journal of Psychedelic Studies (Brown and Brown 2019) which reviewed Panofsky’s role in the Wasson-Allegro dispute. The authors also collected additional images of mushrooms in medieval art. They publish Panofsky’s original letters to Wasson, including the second letter in which Panofsky states that an ‘especially ignorant craftsman may have misunderstood the finished project […] as a real mushroom’ but that is unlikely since the tree has branches which mushrooms do not have. The authors claim that fly agarics often grow in clusters, and that given the lack of perspective the mural might show a grown mushroom surrounded by recently emerged mushrooms (p. 144, 147).

Their fieldwork exploration of mushrooms – or entheogens – in medieval Christian art, which they describe in detail in their The Psychedelic Gospels (2016), includes a (supposed?) fly agaric featured upside down on the forehead of a ‘green man’ at Edinburgh’s Rosslyn chapel (1446) (Fig. 5), several images from murals at the Church of St. Martin de Vicq, not far from Plaincourault (early 12th century), a stained glass window depicting Saint Eustace ‘flanked by sacred mushrooms’ at Chartres Cathedral (12th century) (Fig. 6), and images from the Great Canterbury Psalter (13th century; for a complete reproduction, see https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10551125c).

In light of the highly controversial nature of the study of mushrooms in medieval art, including their own theories, Brown and Brown end their article with a call for ‘an Interdisciplinary Committee on the Psychedelic Gospels’, which could help establish a rigorous methodology for testing their controversial theory. I would be curious to know if such a committee will ever materialize. In the meantime, I am glad to have become acquainted with this line of study, but I also happily admit that I prefer mushrooms in a forest to entheogens in Christianity.

Further reading

- Allegro, John M., The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. A Study of the Nature and Origins of Christianity within the Fertility Cults of the ancient Near East. (Garden City, N.Y., 1970).

- Brown, Jerry B., and Julie M. Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels: The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity (Rochester, VT: Park Street Press, 2016).

- Brown, Jerry B., and Julie M. Brown, ‘Entheogens in Christian art: Wasson, Allegro, and the Psychedelic Gospels’, Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2) (2019), pp. 142-163. DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.019

- Irvin, J.R., The Holy Mushroom: Evidence of Mushrooms in Judeo-Christianity (Grand Terrace, CA: Gnostic Media, 2008).

- Kuhlmann, Antoon, and Dominique Clement, Paddenstoelen in kunst, cultuur en natuur (Zeist: KNNV Uitgeverij, 2020).

- Rush, John, The Mushroom in Christian Art: The Identity of Jesus in the Development of Christianity (Berkely, CA: North Atlantic Books, 2011).

- Wasson, R. Gordon, Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1968).

- Winkelman, Michael, ‘The Holy Mushroom: Evidence of Mushrooms in Judeo-Christianity. A critical re-evaluation of the schism between John M. Allegro and R. Gordon Wasson over the theory on the entheogenic origins of Christianity presented in The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. By J.R. Irvin [Book review]’, Anthropology of Consciousness, 21.1 (2010), DOI: 10.1111/j.1556-3537.2010.01023.x