Medieval Photoshop

Manipulating and enhancing images may seem something that is particular to the current digital age. The Kattendijke Chronicle, a late fifteenth-century manuscript from the Low Countries, contains fascinating examples of analogue image editing.

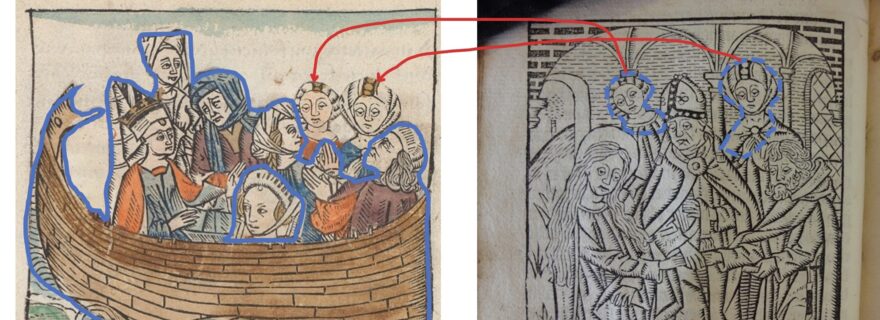

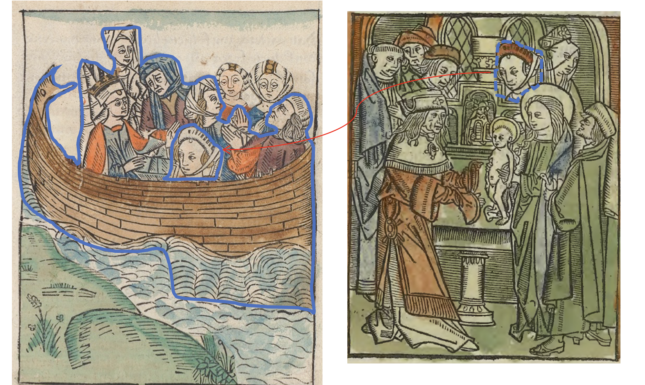

At first sight, the image of a group of people in a boat might appear to be a straightforward woodcut that was pasted into a manuscript (fig. 1). Since single leaf prints – woodcuts and engravings – were used more often in handwritten books from the second half of the fifteenth century (see e.g., Rudy 2019), this example might not seem particularly special. A closer look, however, reveals several indications that there is much more to this image than meets the eye. The somewhat slant lines that frame the image and the inconsistency in the way the water between the ship and the strip of land is represented, point to analogue manipulation of the image. Before examining these edits further and looking into their relevance and meaning for the design of late medieval images, a brief introduction of the manuscript is in place.

The Kattendijke Chronicle

The so-called Kattendijke Chronicle derives its name from its seventeenth-century owner, Johan Huyssen of Kattendijke (1566-1634). In the 1990s his descendants made the manuscript available to a small team of researchers, which in 2005 resulted in an edition with an in-depth introduction that focused on textual, heraldic and codicological aspects, and explored the profile of the author of the Chronicle (Janse et al. 2005). The latter worked in Holland (possibly Haarlem?) and completed the book in or shortly after 1491. Van Anrooij, Biemans, and Janse regard him as the mastermind behind the whole manuscript and characterize him as a lay man (i.e., not a professional intellectual) and a talented bookmaker. Nowadays the manuscript is kept at the Royal Library in The Hague and is available online in a high-quality digital format (https://www.kb.nl/kattendijkekroniek).

The text is a compilation of at least six fifteenth-century sources, mainly chronicles that circulated in both manuscript and print. They include the Dutch translation of the Fasciculus temporum printed in 1480 by Jan Veldener at Utrecht, the so-called ‘Gouds kroniekje’ or ‘Little Gouda chronicle’ (Chronike of Historie van Hollant, van Zeelant ende Vriesland ende van den sticht van Utrecht), published by Gerard Leeu in 1478, and two historical novels by Raoul Lefèvre, published by Jacob Bellaert at Haarlem (1484-1485). Most of the Chronicle is the result of intricate methods of textual compilation that have been described by Antheun Janse. At times the author uses multiple sources simultaneously and interweaves them into a ‘new’ text, in other instances he takes substantial passages from existing texts which he uses as building blocks to create a new narrative. Similar patterns of compilation can be observed in the images that accompany the text.

Mixed media images

Originally, the codex contained no less than 144 images. Even though many of them are no longer in place – the image of Louis the Pious is illustrative (fig. 2) – the images are still intact can help reveal the editing process. All images can be considered ‘mixed media images’: they are made up of woodcuts and/or engravings, enhanced through painted elements and coloring. The use of engravings in the Kattendijke Chronicle has gone unnoticed until now. I hope to discuss the various editing strategies employed in the manuscript in an upcoming article based on a paper I presented last October during a conference on ‘Customized Books in Early Modern Europe, 1400-1700’ (Atlanta, Emory University). Here, I will explore a single example that beautifully shows how a new composition was creation out of elements of woodcuts from a variety of sources.

Albina and her Sisters

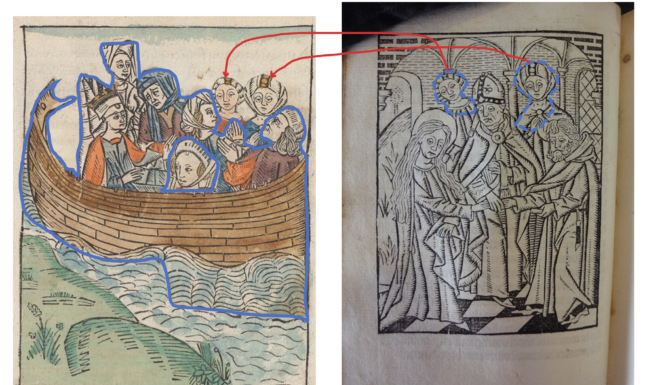

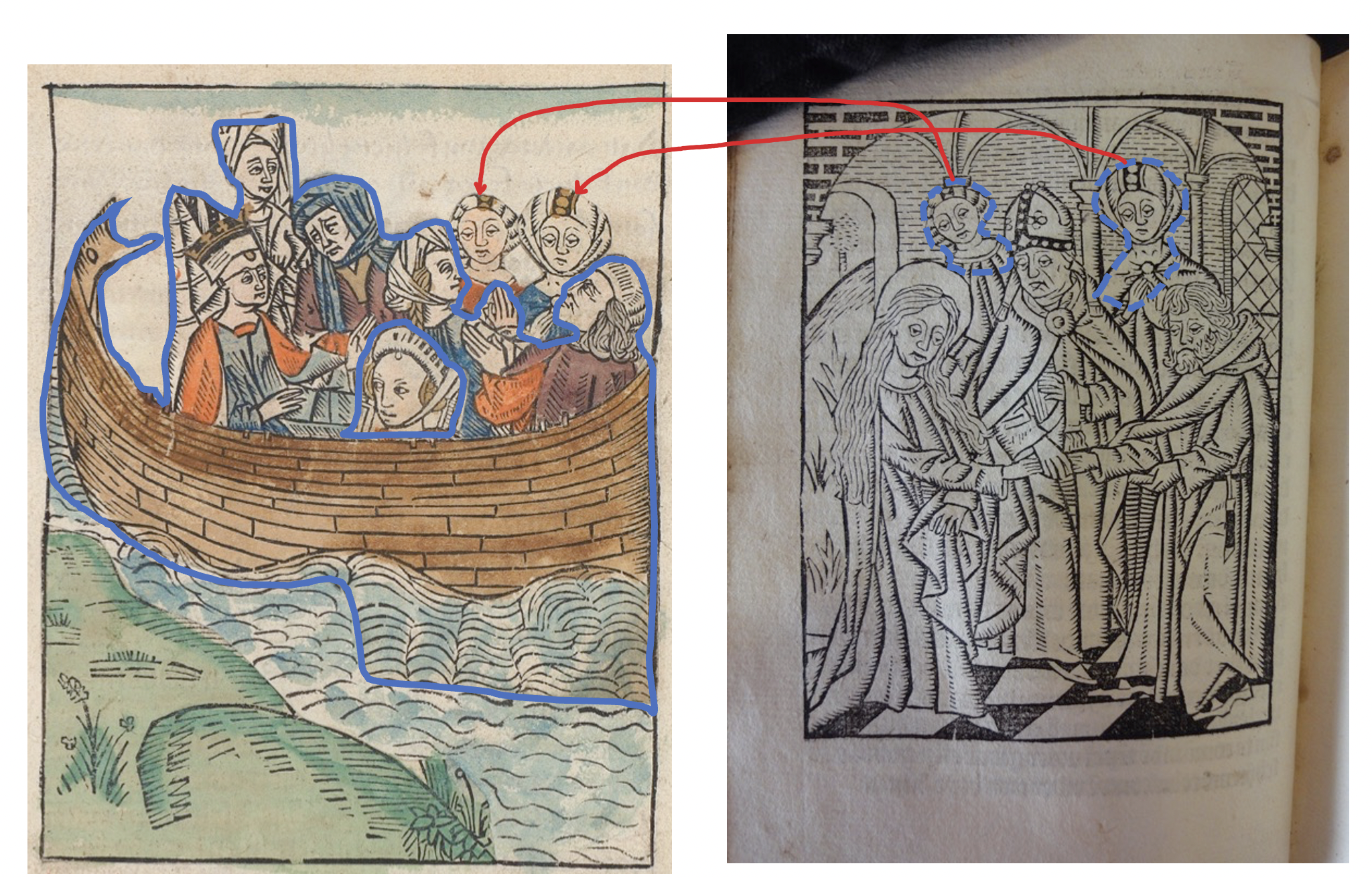

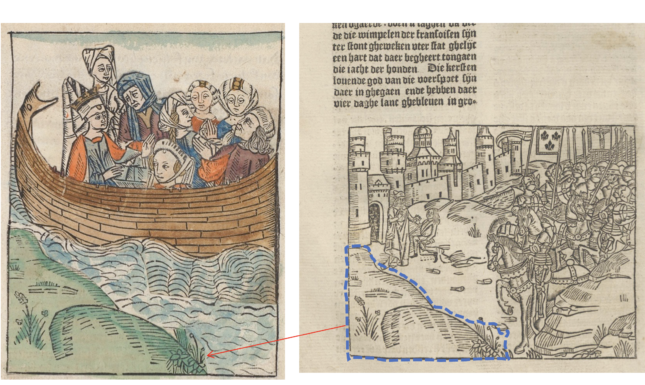

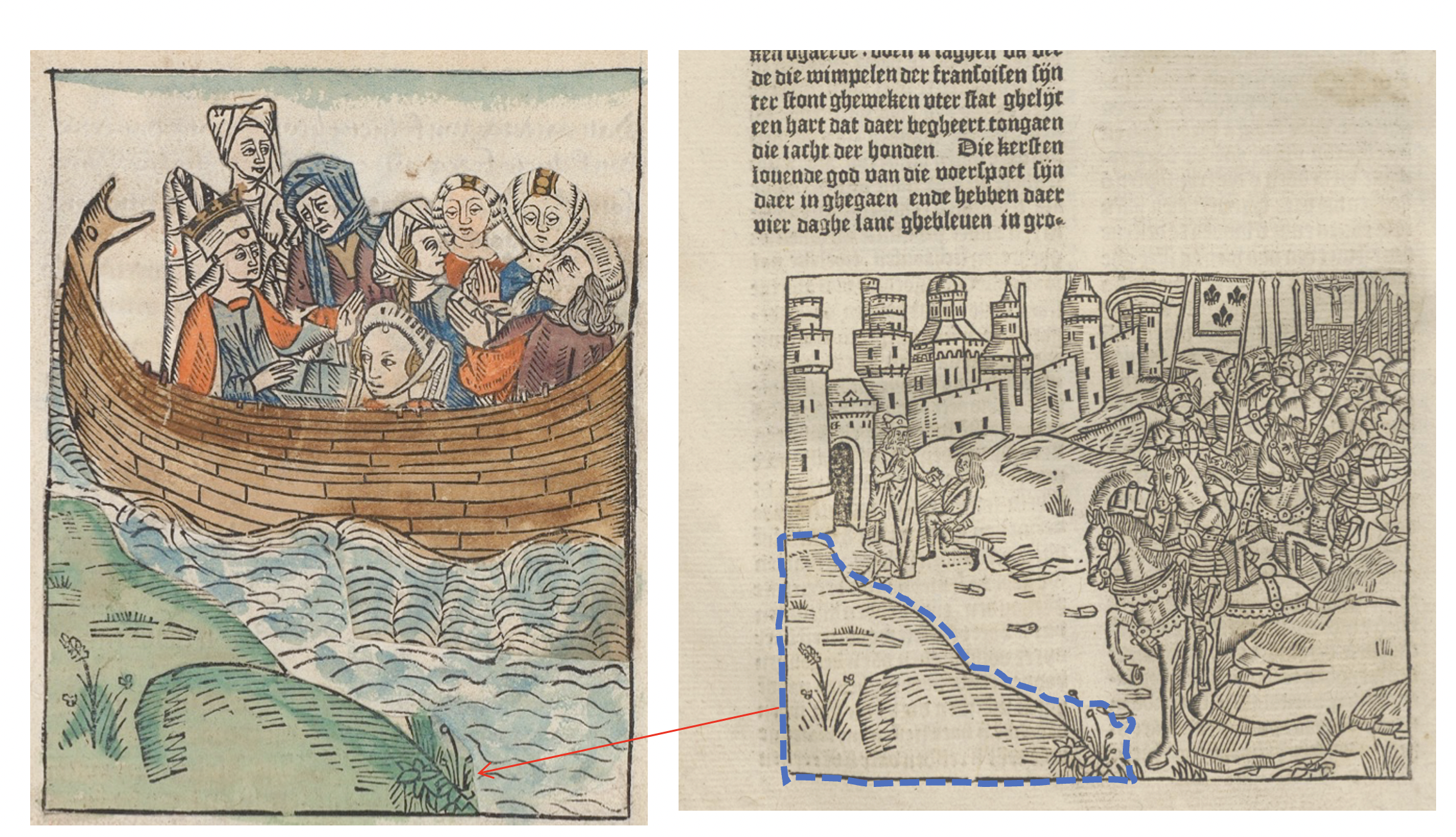

The image that portrays a ship at sea with the exiled Queen Albina and her sisters, who, according to legend would eventually end up in Albion (now Britain), is compiled out of prints from four different woodcuts. The ship and a major part of the company come from a woodcut of Christ preaching with the parable of the sower in the background, originally designed and cut for the 1487 edition of the Book on the Life of Christ (Boeck vanden leven Ihesu Christi), printed by Gerard Leeu at Antwerp (Kok 2013, no. 85.27; Janse et al. 2005). Christ and his apostles had to make place for the crowd that originally occupied the shore (fig. 3).

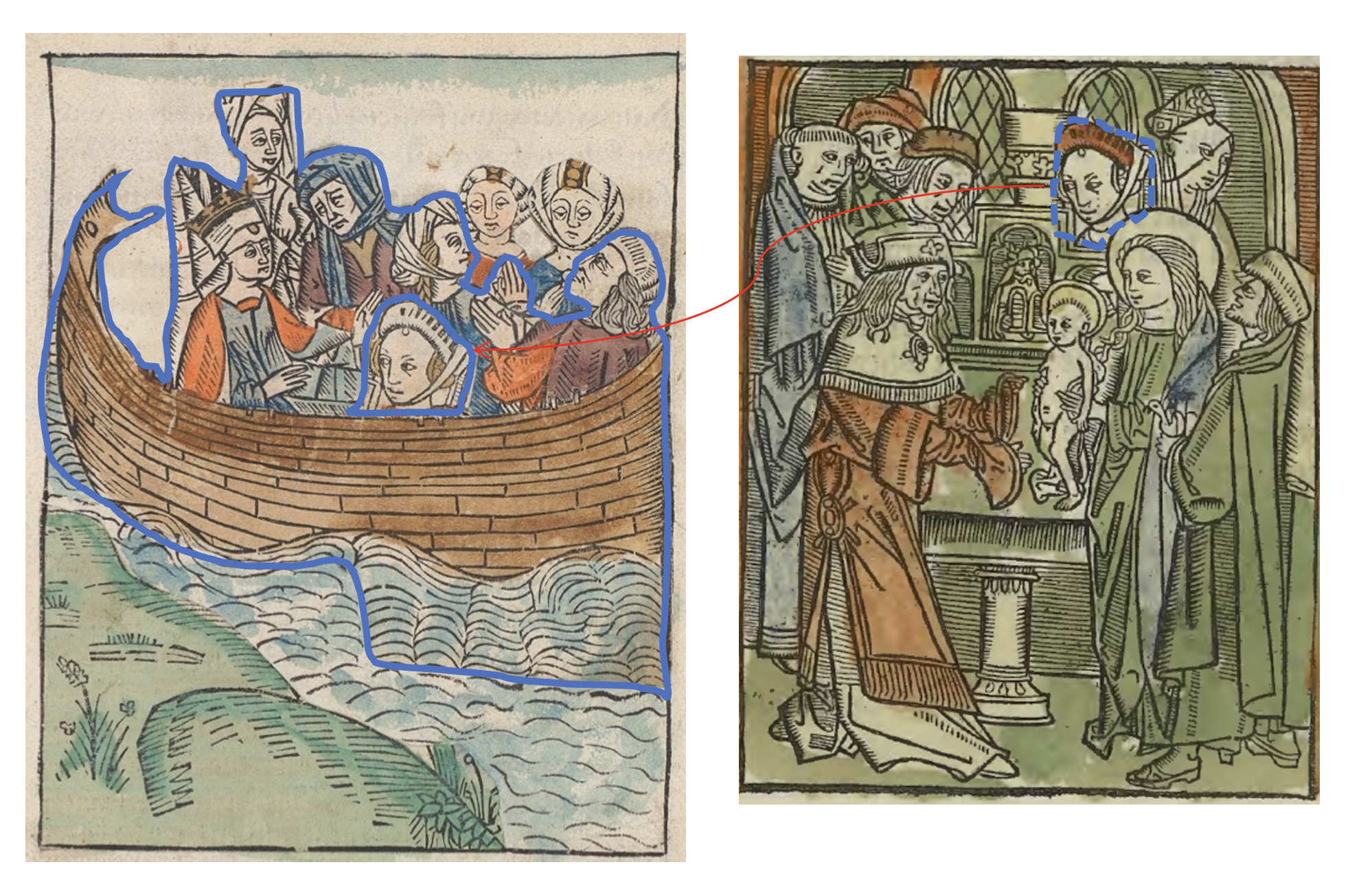

To make the ship more crowded (Albina, after all, had thirty sisters), two female heads were lifted from a woodcut of the ‘Marriage of Mary and Joseph’ that belonged to an important woodcut-series that Gerard Leeu used in many of his devotional editions (Kok 2013, no. 74.7; Dlabacova 2017) (fig. 4).

There was space for one more sister, and she was lifted from a woodcut portraying the ‘Presentation of the Christ Child at the Temple’ (fig. 5), originally created for the 1488 Delft edition of the Boeck vanden leven Ihesu Christi (Kok 2013, no. 37.9).

The ‘new’ shore was lifted form a woodcut made to illustrate the story of Godfrey of Bouillon, leader of the First Crusade, in Dutch (Kok 2013, no. 187.10). Finally, the additional waves between the woodcuts were drawn in by hand and the new image was colored (fig. 6).

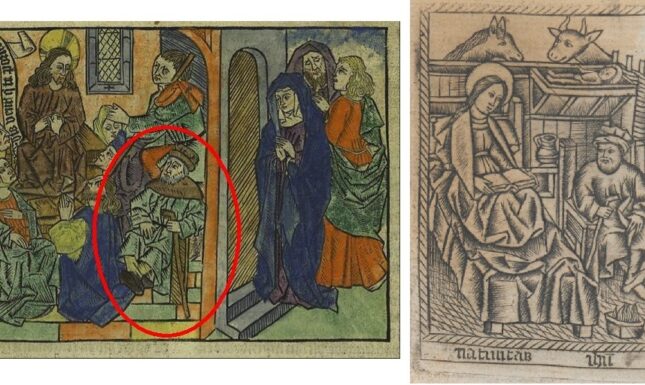

‘Who is that Guy?’ Revisited

The very first blogpost I wrote for the Leiden Medievalist Blog (https://www.leidenmedievalistsblog.nl/articles/whos-that-guy-identity-crisis-in-a-fifteenth-century-woodcut) focused on a woodcut image of ‘Christ preaching and a woman in the crowd raising her voice’ (Kok 2013, no. 85.37). This image has always fascinated me, particularly because of the figure that seems to meet Christ’s gaze, in the bottom right corner of the room. He is the same figure that represents Joseph in a Nativity scene that was widespread in engravings and woodcuts (fig. 7). Knowing the techniques used in the Kattendijke Chronicle I can now imagine the woodcut designer had the engraving in his stack of images and was looking for figures to fill the room around Christ. Once aware of the compilation techniques, you also start to notice that other figures in woodcut images have an odd position or seem to be somewhat floating. In the case of this woodcut, the figure to the right of Christ, for example, hovering over Joseph, seems to be a ‘re-contextualized’ shepherd from an Adoration scene, although I have not been able to identify him.

A study of the mixed media images in the Kattendijke Chronicle leads to a better awareness of the strategies employed by woodcut designers. Knowledge of this highly physical process can facilitate a new way of looking at and appreciating woodcut images. It allows us to notice different aspects of woodcuts, like reoccurring figures which can be encountered in various Netherlandish woodcut series. All too often we tend to set aside cutting out and pasting images as child’s play. The ‘image editing’ or ‘image compositing’ technique that we are confronted with in the image of Albina and her sisters, must have been quite an essential part of late medieval book design, principally when designing images for a particular text. The Kattendijke Chronicle is unique because it almost allows us to see the process of analogue image editing and the compilation of a new composition take place before our eyes. It shows how images could travel and end up in a new composition, and how Joseph might have moved from the Nativity scene to listening to his grown son preach.

Further Reading

- A. Dlabačová, ‘Religious Practice and Experimental Book Production. Text and Image in an Alternative Layman's "Book of Hours" in Print and Manuscript’, Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 9(2) (Summer 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.2.2

- B. Ebels-Hoving, ‘‘Kattendyke’, een goed verpakte surprise’, in: Bijdragen en Mededelingen betreffende de Geschiedenis der Nederlanden, 122 (2007) 1-14.

- A. Janse, W. van Anrooij, J.A.A.M. Biemans, I. Biesheuvel, C.M. Ridderikhoff and K. Tilmans, Johan Huyssen van Kattendijke-kroniek. Die historie of die cronicke van Hollant, van Zeelant ende van Vrieslant ende van den Stichte van Utrecht (Den Haag: Instituut voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis, 2005).

- I. Kok, Woodcuts in Incunabula printed in the Low Countries, 4 vols. (Houten: HES & De Graaf, 2013).

- K.M. Rudy, Image, Knife, and Gluepot. Early Assemblage in Manuscript and Print (Oxford: Open Book Publishers, 2019).

© Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.