Play piggy games, win piggy prizes: Swine entertainment in medieval Europe

At medieval carnivals and country fairs, various games involving pigs took place. This blog post discusses four instances of this remarkable swine entertainment in medieval Europe.

1) The pig-beating game: When four blind men fight over a pig, they end up beating each other

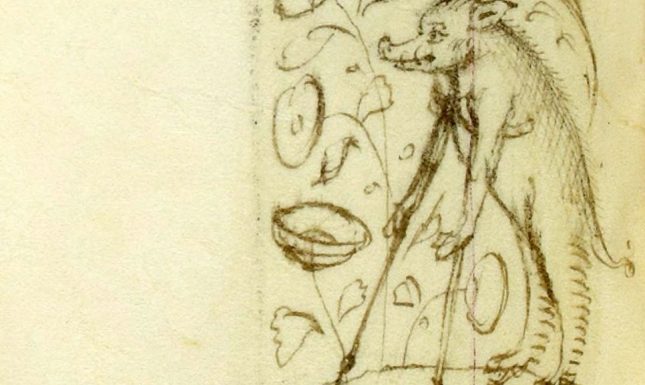

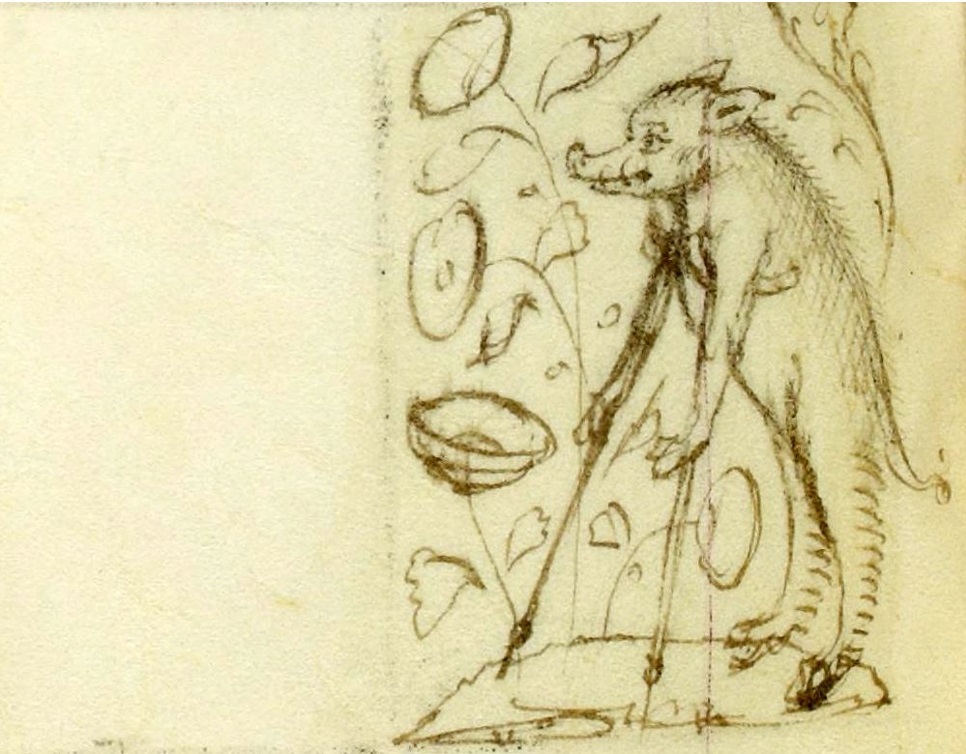

One of the marginalia of a manuscript illuminated by 14th-century Flemish artist Jehan de Grise depicts what appears to be a rather cruel kind of game. In the first drawing, a young boy leads along four apparently blind men carrying clubs; in the next image, the four blind men are hitting each other in the vicinity of a tied-up hog:

As it turns out, these drawings depict a very popular medieval ‘pig-beating’ game that is attested throughout late medieval Europe. The most detailed description of this game comes from an anonymous chronicler describing the following event taking place in Paris, 1425:

Note, the last Sunday of the month of August there took place an amusement at the residence called d’Arminac in the Rue Saint Honoré, in which four blind people, all armed, each with a stick, were put in a park, and in that location there was a strong pig that they could have if they killed it. Thus it was done, and there was a very strange battle, because they gave themselves so many great blows with those sticks that it went worse for them, because when the stronger ones believed that they hit the pig, they hit each other, and if they had really been armed, they would have killed each other. Note, the Saturday evening before the aforementioned Sunday, the said blind people were led through Paris all armed, a large banner in front, where there was a pig portrayed, and in front of them a man playing a bass drum. (cited in Wheatley 2010: 1)

Similar games have been attested in the Low Countries, Germany, and Switzerland, with various chronicles noting the utter amusement of spectators over the blind men hitting each other rather than the pig (Metzler 2013: 162-164). Given the apparent comedic nature of the game it comes to no surprise that the famous satirical medieval artist Hieronymusch Bosch also made a painting of it (regrettably, the painting is now lost, but it was recorded by Spanish humanist Felipe de Guevara in Comentarios de la pintura).

2) The roasted pork race: A competition among crusaders

Another medieval example of having disabled people compete over a pig is reported by poet and author Usama ibn Munqidh (1095–1188). His The Book of Contemplation (c. 1183) contains various descriptions of European crusaders and their peculiarities. These peculiarities include strange medicinal practices (like blocking a dying knight’s nostrils with wax to speed his passing and cutting off a woman’s hair to get rid of the devil in her head), their wild-growing pubic hair(!) as well as a crude form of entertainment involving two old women and some roasted pork. Usama describes the latter as follows:

They positioned the two women at one end of the practice-field and at the other end they left a pig, which they had roasted and laid on a rack. They then made the two old women race one another, each one accompanied by a detachment of horsemen who cheered her on. At every step, the old women would fall down but then get up again as the audience laughed, until one of them overtook the other and took away the pig as her prize. (trans. Cobb, 2008: 150-151)

Here too the impaired people appear to be the butt of the joke; it is their inability to run quickly that entertains the audience. As with the pig-beating game, the swine acts as the reward for this kind of entertainment; other forms of medieval entertainment envisioned a more active role for the pig, or rather: roll.

3) Rolling the pig down the hill.

One of the best documented medieval carnivals are the ‘games of the Agone and Testaccio’, which took place in medieval Rome. this carnival included the awkward game of putting live pigs into carts and rolling them down the hill of Testaccio. The 1363 city statutes describe these carts as follows:

Item sex carrotie duabus que consueverunt per molendinarios fieri ibidem computatis in quibus poni debeant animalia consueta, scilicet, duo iuvenci et duo porci in qualibet carrotia deponantur. […] Et ipse carrotie debeant panno rubeo coperiri ad honorem populi Romani. (ed. Re, 1880: 241)

[Also, six dual carts that are wont to be made by millers in that very place, in which ordinary animals should be placed, that is to say, two young bulls and two pigs should be placed in each cart. … And these carts should be covered with a red cloth for the honour of the Roman people.]

This cruel practice apparently continued well into the 19th century, when the novelist Stendhal witnessed it and described the event as follows: “two carts filled with pigs were hauled to the top of the hill, then allowed to run back down the steep slope to be smashed to pieces along with their porcine passengers. The watching revellers would then dismember the pigs on the spot and carry the parts off to be roasted and eaten” (source).

4) Greased pig wrestling

Racing or wrestling a greased hog is often presented as the typical kind of medieval swine-related entertainment (see, e.g., http://www.medieval.net/catchi... ). However, it is surprisingly difficult to find traces of (let alone get a grip on) greased pigs in medieval sources.

I have only been able to find one off-hand reference in Peter Cantor’s moral guide for clergy, known as the Verbum Abbreviatum (c. 1187). In a passage lamenting the various malpractices of priests (including their love for dice and flamboyant fashion), cantor recounts how some clergymen made a spectacle of themselves, when they rushed into a church, trying to race each other in order to get to a feast:

When the bell rang for the hour of distribution at a certain church, and a bar was set across the entrance to the choir, the clergy ran as though to a solemn feast, even as old women run for the greased pig; some stooping below to enter, others jumping over the bar, and others rushing in disorderly fashion through the great portal, whereby it is lawful for no man to enter save only for the dignitaries of the church. (Trans. Coulton 1910: 121)

Cantor’s comparison between stumbling clergymen running to get a bite to eat and “old women [running] for the greased pig” may be a reference to a game not unlike the one described by Usama ibn Mundiqh above: two old women chasing after a piggy prize. If so, this is one more piece of evidence of how medieval disability intersects with entertainment and ridicule. Somehow, swine were often involved in this mix - were they there to add to the comedic nature of the events since they were considered a ‘base’ animal? Or was there some link between pigs and ill health? That may be something for another blog post..

Little note: Cruelty to pigs is detestable and continues until this present day (no matter how medieval the concept might appear), do consider donating to a pig charity like this one https://familiebofkont.nl/doneer/

References

Cobb, Paul M., trans. Usama ibn Munqidh.The Book of Contemplation: Islam and the Crusades. London, 2008.

Coulton, George G., trans. A Medieval Garner. London, 1910.

Re, Camillo, ed. Statuti della citta di Roma. Rome, 1880. (with thanks to Amos van Baalen for helping me with the translation)

Wheatley, Edward. Stumbling Blocks Before the Blind. Medieval Constructions of a Disability. Ann Arbor, 2010.

Metzler, Irina. A Social History of Disability in the Middle Ages: Cultural Considerations of Physical Impairment. Ann Arbor, 2013

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised useand/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.