Medieval piggyback rides: Riding boars in the Middle Ages

With their ferocious characters, daunting tusks and relatively bulky statures, boars make unlikely steeds. Nevertheless, the Middle Ages feature various examples of boar riding.

Pagan gods on the back of boars

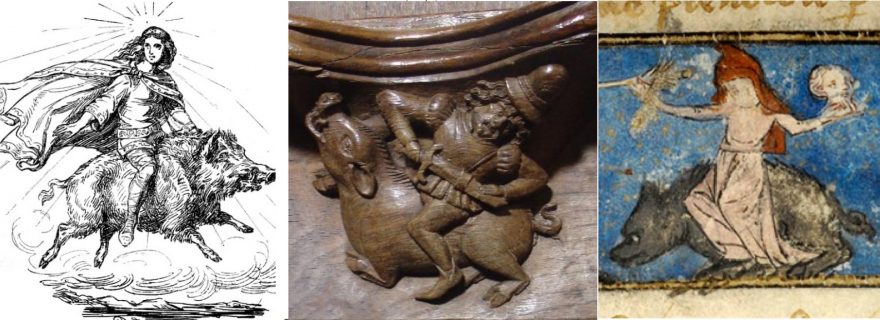

Freyr and Freyja and their pet-boars (source: WikiCommons)

Boars played on important role in Germanic mythology and were associated, in particular, with the Norse gods Freyr and Freyja. Freyr, god of virility, was the owner of the divine boar Gullinbursti (‘Golden Bristles’) whose golden bristles shone brightly as the pair traversed the sky. In some stories, Gullinbursti draws Freyr’s flying chariot, but in the late tenth-century poem Húsdrápa, partially preserved in Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda, Freyr is said to ride on his boar:

Ríðr á bǫrg til borgar bǫðfróðr sonar Óðins

Freyr ok folkum stýrir fyrstr enum golli byrsta.

[Rides in first place, and on a boar with bristles of gold, battle-wise Freyr to the fortress of Óðinn's son and he guides the people.] (ed. and trans. Richard North)

Freyja, the goddess of love, is also associated with a riding boar: Hildisvini ‘battle-swine’, whom she rides in the Old Norse poem Hyndluljóð.

The divine boar steeds of the Germanic gods were gradually imposed onto the classical pantheon in the later Middle Ages - Venus, Freyja’s Roman counterpart, for instance was often depicted riding on a boar. A case in point is found in the allegorical poem Le pèlerinage de la vie humaine by Guillaume de Deguileville (1295-1358):

Venus riding a boar in Le pèlerinage de la vie humaine by Guillaume de Deguileville (source)

Here, Venus, personifying Lust, is seated on a boar, while she holds a mask in her left hand and pierces a pilgrim’s eyes with her dart (showcasing the deceitful nature of Lust). Since boars were associated with lust in the Middle Ages (see: Pigs and Bagpipes: Geoffrey Chaucer’s Miller in Context), the link with Venus (who, here, represent the sin of lust) was easy to make. While boars thus make suitable steeds for personifications of Lust, it is Anger who rides the boar in other medieval artistic traditions.

Sins riding swine

The seven deadly sins (pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath and sloth) are a well-known motif in medieval art. In one variation of this theme, the seven deadly sins ride on various animals. The 14th-century Concordantiae caritatis by Ulrich von Lilienfeld features Luxuria (Lust) riding a stag, wile Ira (Wrath) rides on a boar:

Luxuria and Ira riding their animal steeds in Lilienfeld, Stift Archiv, HS 151 (source); the famous Budapest manuscript of the Concordantiae caritatis on the cover of Richard Newhauser’s book on the Seven Deadly Sins reveals that the steed of Ira is supposed to be a boar.

These riding sins were also a common feature in churches, including the early 15th-century misericords of Norwich Cathedral. Here, Wrath (with wild flowing hair, drawing a sword) is depicted as riding on a boar:

Wrath riding a boar in Norwich Cathedral (source)

Given the boar’s reputation of ferociously attacking its pursuers rather than fleeing, the boar seems a suitable companion to the sin of Wrath.

How a saint saved Charlemagne from a boar

It is not just pagan gods and personified sins who chose to ride on boars: a legend surrounding the the Cathedral in Nevers (France) associates Saint Cyricus with riding on a boar. The legend involves Emperor Charlemagne (d. 814), who dreamt that he was chased by a furious wild boar through a forest. Charlemagne implored the Heavens for divine help, which came in the form of the half-naked child St Cyricus. The child offered help in return for Charlemagne’s garment. Charlemagne conceded and gave the child his cloak; the child mounted the boar and rode away. When Charlemagne awoke from his dream, he learned from his advisors that the child was St Cyricus and that the requested cloak represented money that was to be spent on the restoration of the Cathedral of Nevers, which was devoted to St Cyricus and his mother St Juliet. The cathedral was restored and today it still shows a reference to this boar-legend on the capital of one of the pillars of the nave; a stained glass window of the nearby Eglise de Saint-Saulge also depicts the scene:

St Cyricus astride a boar in Nevers Cathedral (source) and Eglise de Saint-Saulge (source)

An Old English proverb

With the exception of St Cyricus, medieval boar riders do not appear to have had positive connotations in medieval Christian thought and the act of riding a boar, associated as it was with pagan gods and deadly sins, would have been viewed as morally objectionable. In addition, the practice seems highly impractical, given the boars' ferocious and untamed nature. Indeed, an Old English poverb, recorded in the 11th century as part of a collection known as the Durham Proverbs, plays on the lack of control someone might have if he were to ride a boar:

“Nu hit ys on swines dome”,cwæð se ceorl sæt on eoferes hricge

[‘Now it is in the hands of the swine’, said the man who sat on the boar’s back]

The proverb uses an apt metaphor to describe a situation that is out of one’s control. Once you get on the back of a boar, you no longer control where you are headed: your fate lies in the hands [dome = judgement] of the swine. Something to keep in mind, perhaps, if this post has inspired you to take a piggyback ride.

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.