Meeting the medieval villagers under the old oak tree

A linguistic window on a fourteenth-century Brabantine village

Introduction

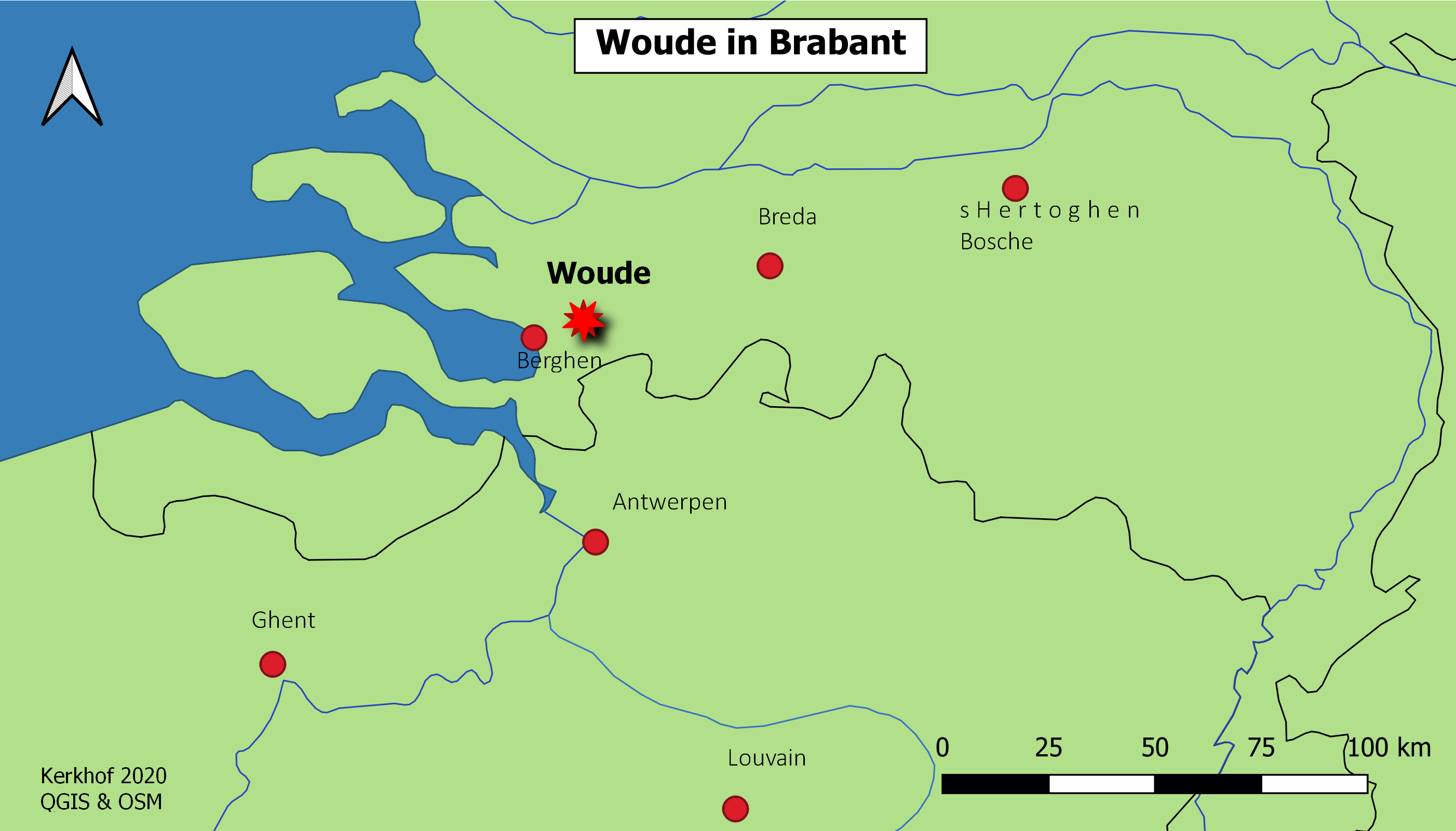

This is the story of an old oak tree. This tree was the last tree standing on what used to be a forested hilly ridge between two rivers in the northwestern part of the duchy of Brabant. In the middle of the twelfth century, a group of farmers from the north had cleared away the forest and built a fortified homestead there. They called this place Woude, after the woodland that used to be there. A hundred and fifty years later this first homestead had grown into its own seigneury, situated between Bergen op Zoom and Breda and covering half a dozen hamlets. In this post I would like to tell you something about the ordinary farmers who lived there, the fourteenth-century villagers who grew up under this old oak tree.

Woude in Brabant

Our access to the past

Most narrative sources from the Middle Ages tell us very little about everyday village life beyond tropes and stereotypes. Unfortunately, those who controlled the means of literacy were rarely interested in the low-born. The village of Woude, for instance, is only mentioned a few times (as a seigneurial title) in these narrative accounts from the Middle Ages. This is why we have to turn to a different type of source if we want to know more about its inhabitants: tax rolls and registers from the southern Low Countries provide a valuable window on this deeply rural region where there were few monasteries and only a couple of towns. Tens of thousands of names of tenant farmers, local landowners and village officials can be found there. It is not in the leather-bound books of the nobility that we find the peasants of the fourteenth century, but in the ledgers and crusty rolls of the tax collector.

Between place-names and personal names

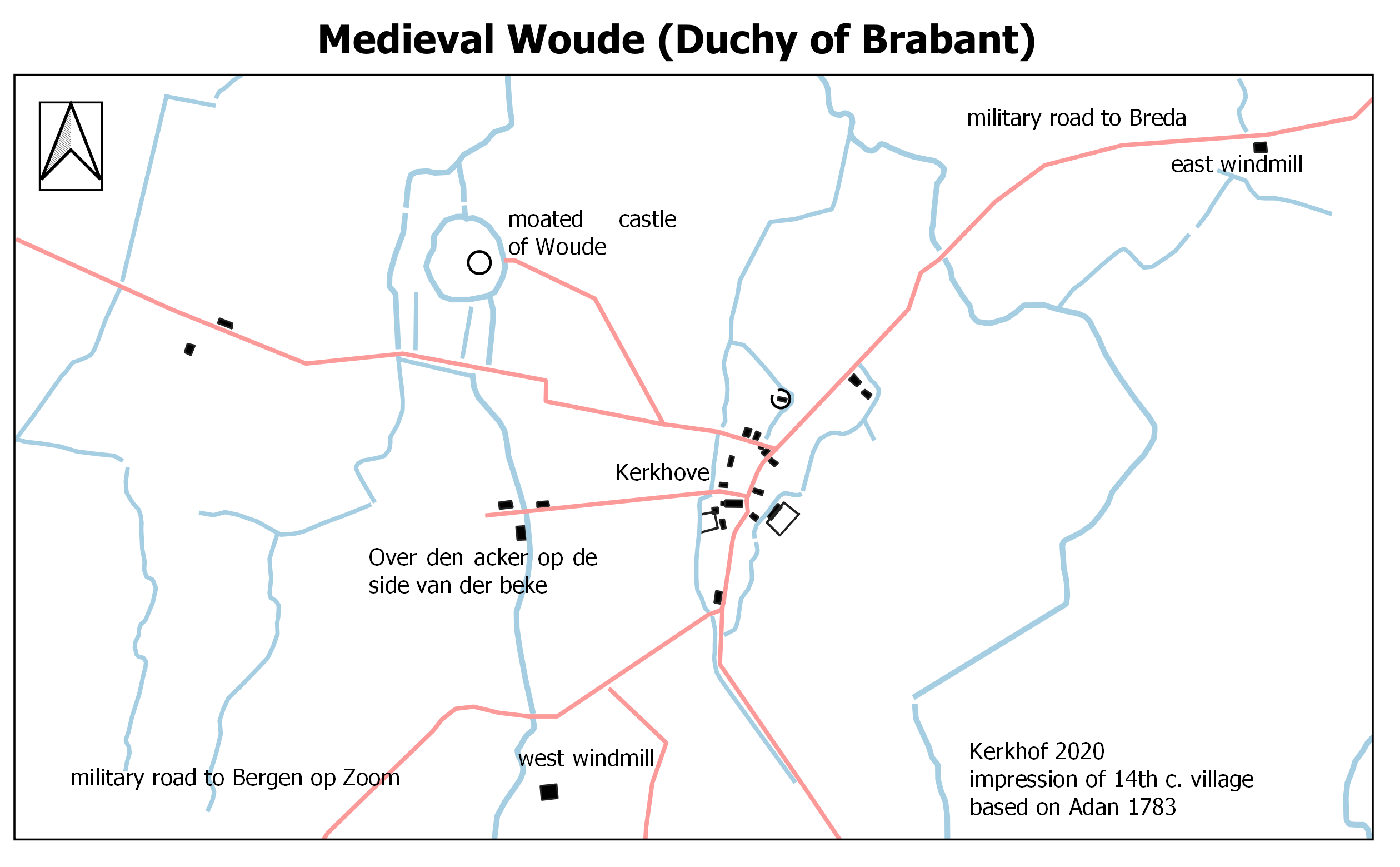

From these tax rolls and registers, we learn quite a lot about the tiny Brabantine village of Woude. Some of this information is directly accessible to the historian: the registers inform us there was a moated castle on the western end of the village and there were two windmills that served the village community. We learn about the old oak tree near the church and how many roods and acres of the surrounding landscape were under cultivation. Other information is less accessible to the historian and comes in the form of onomastics. An important source are the names that were given to fields, meadows and features of the landscape. Several of these names like triest (< OWall. tries “fallow land”) and saer (< OWall. sart “field clearing”) were borrowed from a northern variety of French, showing that noblemen from the south and their bilingual chancelleries were involved in the development of new agricultural land (forthc. Kerkhof 2020). Another source are the personal names with which these tenant farmers and land owners were identified in the tax records. Linguists can use these personal names to extract information about migration patterns and village networks.

Map of medieval Woude

Identifying the community members

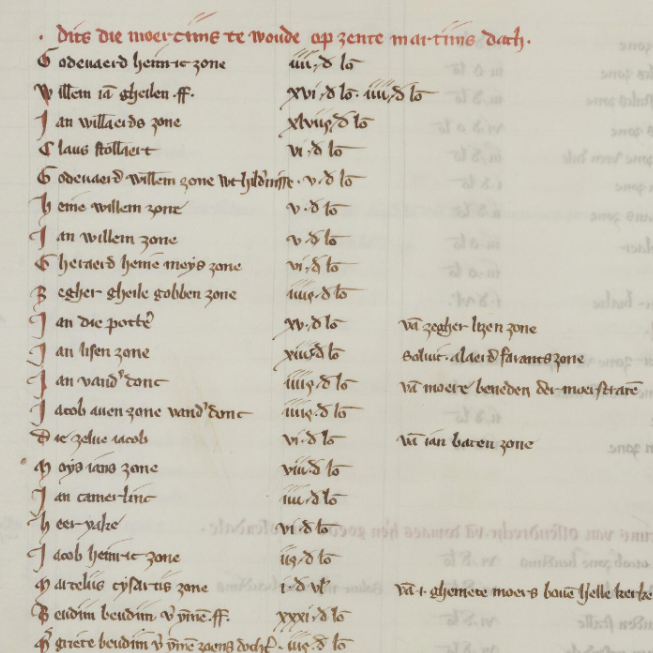

A snapshot of everyday life in the village of Woude comes from a tax register dated to 1359 (ARR BoZ, inv. 597). In this ledger, we find a thriving rural community, seemingly untouched by the horrors of the Black Death. The taxes are organized by revenue type, starting with the hay tithes and continuing with the land tax and moor rents (see also Van Loon 1966: 57-63). The name of each and every taxable person is listed in the register, along with any additional identifiers; Often the parentage was included, but also nicknames of profession and/or geographical origin could be given. To give you an idea of what such an entry looks like, here is one from the revenue post of the oude lantciins te Woude (the old land tax of Woude) in the community of kerkhove (the church homestead):

- Jonghe heinric van der beke = young Henry of the Brook

- 1 d lo van 1 gemet maden te Rosendale = 1 louvain denier deriving from 1 gemet of meadow land in Rosendale

This might not look like much, but it is exactly this kind information that allows us to go deeper than what the register intends to relate to posterity. In the case of the aforementioned Heinric, we learn that he is the younger of two persons who have that name. Additionally, the geographical identifier van de Beke (of the Brook) tells us that his family came from a different hamlet within the parish, the group of farms on the side of the brook.

The register also informs us that even though the settlement was probably founded by Hollanders, a reasonable number of the population came from Zeeland. This is evident from geographical identifiers referring to the Zeelandish towns of Hulst, Yrseke, IJzendijke and Borsele. In line with these identifiers, we often find people with the cognomen die Sewe = the Zeelander, which seems to corroborate the connection to Zeeland. This linguistic data provides us with a picture of landless commoners migrating from the Zeeland islands to the duchy of Brabant and becoming tenant farmers on a Brabantine manorial court.

Register, ARR BoZ 1359, f. 61v.

Names and anecdotes

Another unique window on everyday life comes in the form of a different type of nickname, nicknames like de lange (=the long one), de blide (=the happy one) and doude (=the old one). Some of these names were in all likelihood connected to anecdotes that everyone in the community would know, but can no longer be accessed by us. This is why we are left to guess why someone would be called de loddere (=pervert), druut (=lover), bulgier (=heretic), peppersac (=pepperbag) or bille (=butt cheek). For other names it is easier to understand why they would have been given, e.g. struus (=large), stercman (=strongman), metten swere (=with the ulcer) and sceluwaerd (=squint-eye). Although these names were recorded for the purpose of identifying taxable people, they tell an immensely personal story of what these people looked like and what the community thought of them. This story becomes even more personal when it turns out that someone who is called de rike (= the rich one) actually paid one of the lowest rents in the village. It is therefore very likely that the name was used in jest.

Gender relations

The register also tells us another tale that is hard to find in any other type of source; the economic position of peasant women, something which is rarely commented upon in literary sources. From the register it becomes clear that in this Brabantine village community peasant women were independent taxable parties. Here is an entry from the revenue post of the hoinere te Woude (the hay feed tax):

- Heilwi pluegers wiif = Heilwi, the wife of the plowman

- 4 d lo (Louvain deniers)

This Heilwi is hardly the only woman to be mentioned in this capacity. Of the 316 parties that belong to this revenue post, 27 are women. If we extrapolate this number ratio to the rest of the register, this means that slightly less than ten percent of the revenue streams in the register come from married housewives who were apparently taxed for the land that they owned separately from that of their husband.

It is also interesting to note that many men were identified by who their mother was. Here instead of the expected patronymic “name of father-GENITIVE” + “son” we find “name of mother-GENITIVE” + “son”:

- Liediin lizen zone = Liediin, the son of Lize

- 5 ½ d lo (Louvain deniers)

Such cases in which only the mothers name is used as an identifier add up to 36 out of 316. This amounts to about eleven percent of the taxable parties of this revenue post.

There is another intriguing women-related factoid in the register: on two occasions, a man is identified by the woman to whom he was married:

- Jacop mayen man = Jacob, the husband of May

- Jan margrieten man = Jan, the husband of Margriete

However, judging from the numbers, this seems to have been the exception and not the rule. In short: the image that we get from the tax records is that women had a lot of local standing within the community and possessed their own landed wealth separately from their husbands.

Continuity and change

This snapshot of the village from 1359 can be compared to a later one from the early fifteenth century. In a very similar tax register (ARR BoZ, Inv. 1338), written down about three generations later, we find many of the same families still living in the same hamlets within the parish, paying the same rents and living similar lives. However, some things had changed. There were fewer taxable people living in the village, a fact which may be explained by an epidemic striking the community (especially since there are no records of a major military campaign in that region between 1359 and 1424). In addition, a reasonable number of new people had moved in, many from other parts of the duchy, like Antwerp, Turnhout, Ginneken and Goirle. Part of the demographic decline may therefore have been remedied by migration.

Epilogue

In the century that followed, village life continued the way that it had. In 1480, the villagers decided to replace the parish church with a majestic new building in the Kempen architectural style. The castle was modernized and prepared for the age of gunpowder. New towers and living quarters were built. However, disaster struck in the sixteenth century: during the last Guelders war the village burned and the population fled. A couple of years later, some of the old inhabitants returned and rebuilt their farms, but the proud oak tree that had been the center of the community in the Middle Ages was gone, never to be mentioned again. The Middle Ages were truly over and the Early Modern period had begun.

.jpg)

18th-century pen drawing of Wouw castle ruins (1671) by B. Klotz

Primary sources

ARR BoZ = Archieven van de Raad en Rekenkamer van de Markiezen van Bergen op Zoom

Inv. 597, Legger van vaste inkomsten (landcijns, moercijns, hooitienden, lakenaccijns) in het land van Bergen op Zoom en te Brecht, 1359.

Inv. 1338, Legger van cijnsplichtige personen of van in cijns uitgegeven percelen van Wouw, met de gehuchten onder Roosendaal, Kruisland en Langdijk, 15e eeuw.

Bibliography

Van Ham, W. (1980). "Wouw in de Middeleeuwen,” in: Woide...die Wouda; opstellen over de geschiedenis van Wouw, 41-152.

(forthc.) Kerkhof, P.A. (2020). “Calwentriest en Den Trieste: vreemde veldnamen tussen Wouw en Roosendaal”. Handelingen van de Koninklijke Commissie voor Toponymie en Dialectologie.

Leenders, K.A.H.W. (2018). “Rond de oude eik. Wouw en Roosendaal voor 1300”. Jaarboek De Ghulden Roos 78, 9-41.

Van Loon, J.B. (1966). "Grondgebruik in Noord-Brabants Zuidwesten in de Middeleeuwen". Jaarboek de Ghulden Roos 26, 17-138.

© Alexia Kerkhof and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Alexia Kerkhof and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.