Mind the Reader? Intention and Reception in the Early Age of Print, 1450-1600

In the 15th century the novel medium of print and the vernacular languages spoken across Europe became a powerful combination. Printers increasingly published in the vernacular, tapping into new markets. Who read in the vernacular, why, and how?

In the 15th century the novel medium of print and the vernacular languages spoken across Europe became a powerful combination. Printers increasingly published in the vernacular, tapping into new markets. Who read in the vernacular, why, and how?

Vernacular Books

Between c. 1450 and 1600 the new medium of print evolved into a full-grown means of communication and articulation. Initially Latin prevailed, but the vernaculars quickly gained ground in printed book production as languages of arts and sciences, religion, commerce, politics, and literary expression. The choice to publish in a vernacular language was a fundamental decision that formed an integral part of the strategies employed by book producers – who included printers as well as authors, publishers, typesetters and illustrators. Who did they consider their target audiences for vernacular books? What were their considerations and how did they tailor a book for vernacular readers? And how did producers’ intentions relate to readers’ reception?

These questions are at the heart of the international conference ‘Vernacular Books and Reading Experiences in the Early Age of Print’, to be held on 25, 26 and 27 August 2021 (https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/events/2020/08/vernacular-books-and-reading-experiences-in-the-early-age-of-print). Bringing together scholars working on a variety of languages, texts, and in various time frames, this conference aims to work toward a comparative, transnational and interdisciplinary perspective on experiences of vernacular reading. By way of a preview, this post explores the dynamics between intentions and presentation strategies and the actual reception of early printed books in the Dutch vernacular.

Intention vs. Reception

The intended readership and use of a book can be deduced from material aspects such as the size of a book, its lay-out and typography. So-called ‘paratexts’ such as title pages, prologues, epilogues and tables of contents can equally betray the type of reader and usage producers had in mind when making the book. The question of the trustworthiness of these sources still remains largely open. To what extent do they reflect a book’s actual reading audience and the practices of real readers? In order to reconstruct reading experiences of real readers, an examination of the traces they left in printed books can provide essential information.

Reading a herbal in Dutch

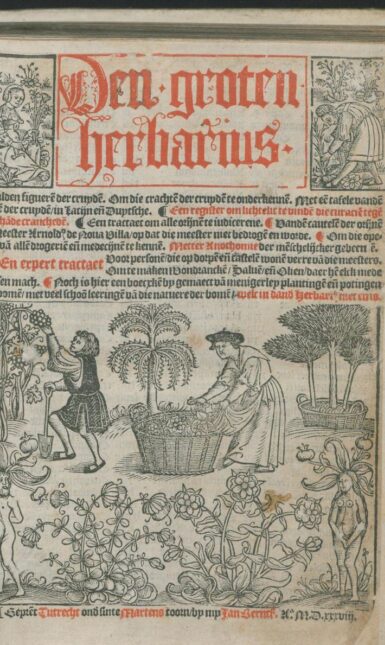

For example, the preface of the herbal Den groten herbarius, printed at least six times between 1514 and 1547, claims that the book will benefit both the learned and the unlearned. The 1538 edition, moreover, includes a medical manual aimed at quite a specific audience: according to the title page, it was meant ‘for people living in villages and castles far away from the masters, to make potions, ointments and oils with which anyone may heal themselves’. (Fig. 1)

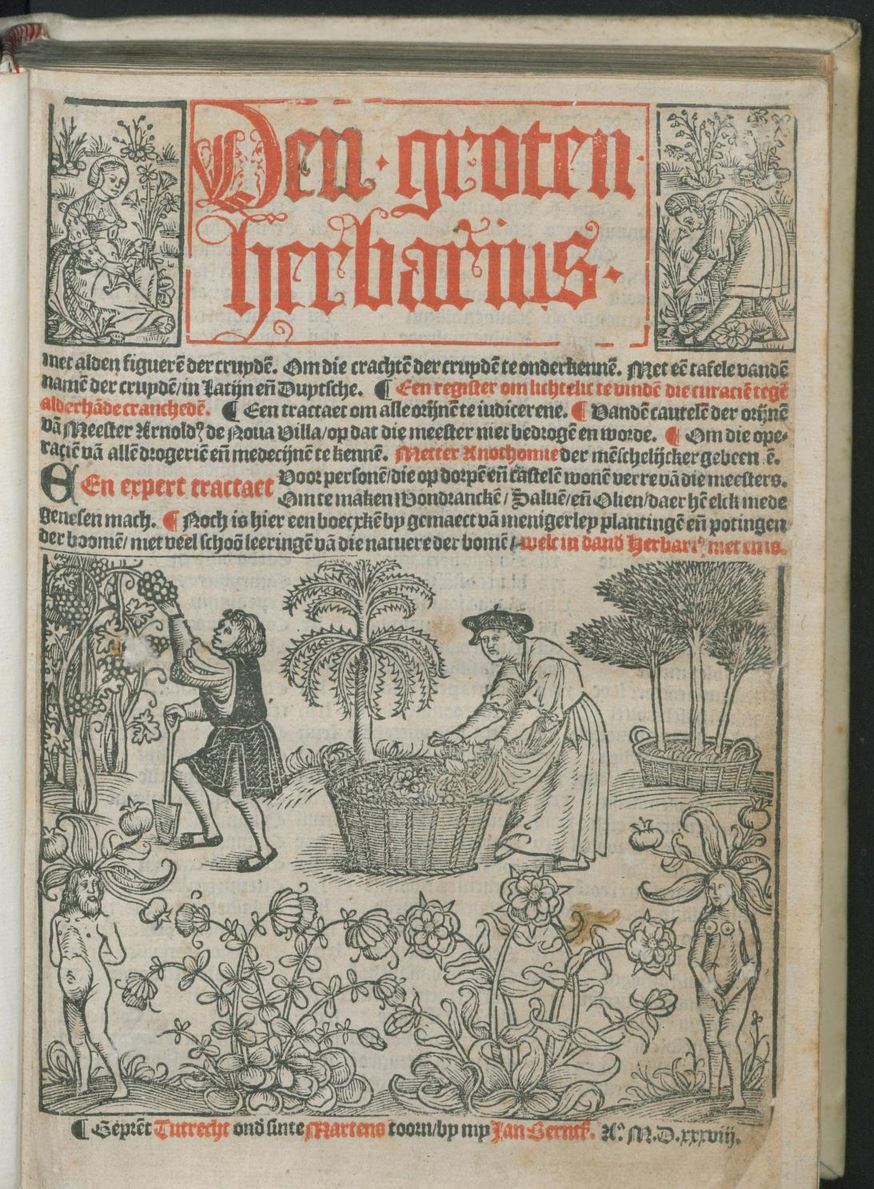

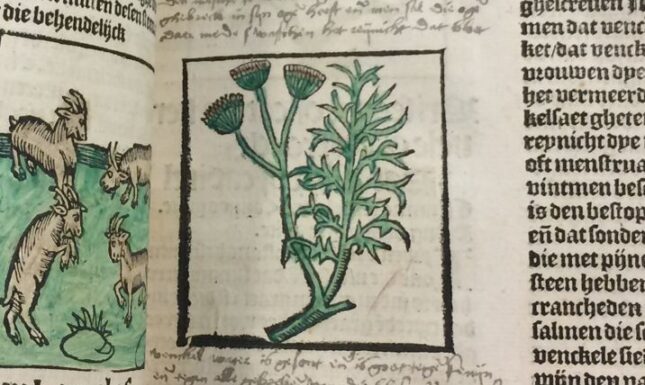

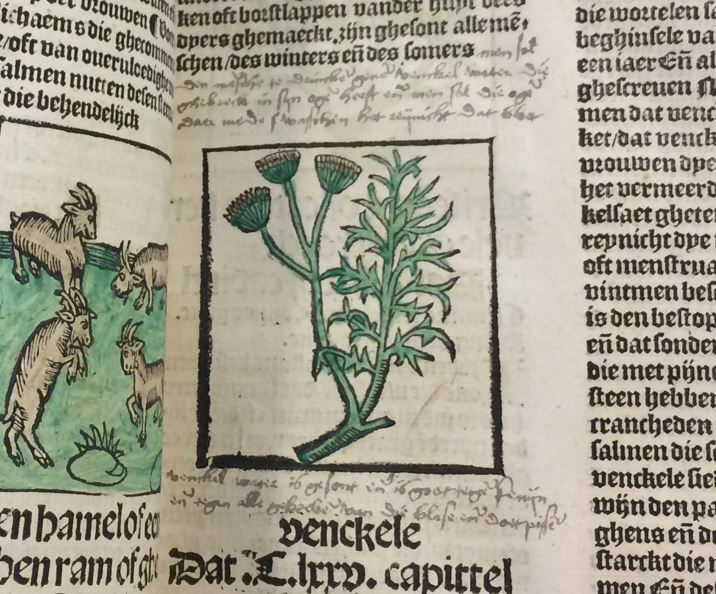

Other aspects of the book’s design, including its selection of images, also point to endeavors by the producers of the various editions to include non-expert readers in the target audience. Most notably, the woodcut illustrations not only show medicinal herbs but also lively scenes of people engaged in extracting, processing, exchanging or consuming a variety of natural resources and products including gold, chalk, magnet stone, cheese, and cream of tartar (Fig. 2).

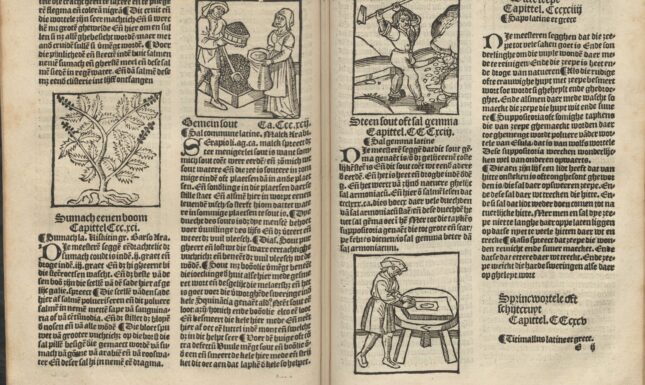

A study of early modern annotations in 27 copies of this title suggests that the printers succeeded in reaching experienced practitioners as well as lay readers (Van Leerdam 2021). While some additions and comments suggest quite knowledgeable readers, a striking number of annotations pertain to recipes against everyday ailments such as colds and toothache. Moreover, there are annotations in Latin but the vast majority is written in Dutch. In the copy of Den groten herbarius from 1514 held at Rijksmuseum Boerhaave in Leiden, a sixteenth-century annotator named Willem Barentsoen has added many recipes and notes on the medicinal efficacy of various substances, all of them written in Dutch (Fig. 3).

Thus, he turned the printed book into a personalised store of medical knowledge, enriched even further through beautiful hand-colouring. We do not know whether Willem was a professional practitioner, but his neatly written notes in any case reveal a dedicated endeavour to gather and record remedies against a variety of common ailments. The volume remained within Willem’s family: his grand-nephew Lambertus Optio (Opsy; 1583–c. 1619) has also inscribed his name on the title page.

Publisher, Reader or Both?

Due to the nature of the processes of early printed book production and the acquisition of copy by printers, intention and reception are closely intertwined. The roles of ‘producer’ and ‘user’ or ‘reader’ are, in fact, not as clearly delineated as one might initially think. Creating a vernacular version of a Latin work required careful reading and an extensive usage of the text in the editing process. As such, the development of print culture added new impulses to the dynamic relations between Latin and the vernaculars.

Publishing an Extract from St Bridget’s Revelations in Dutch

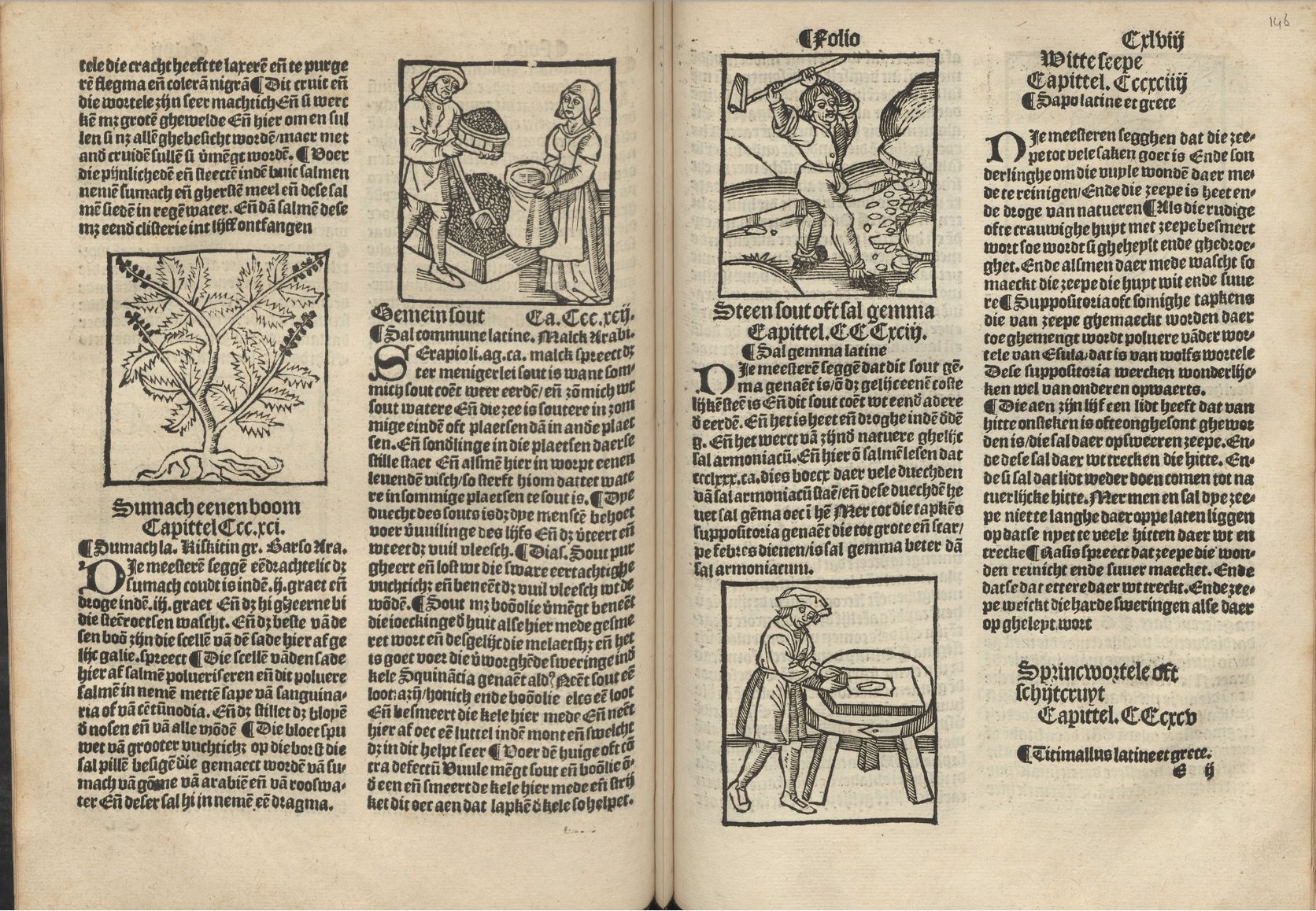

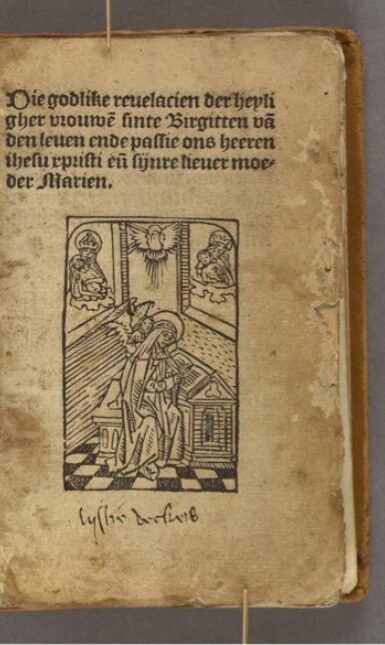

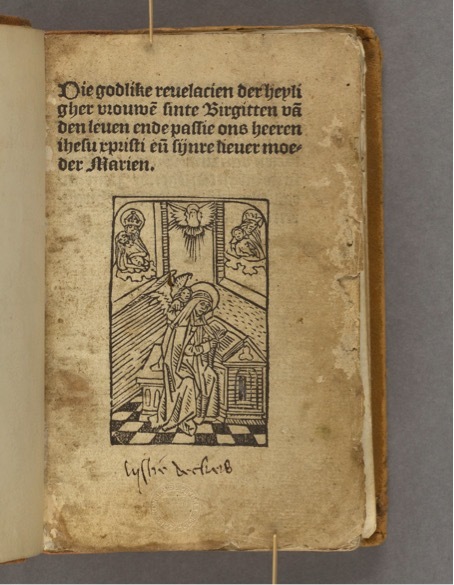

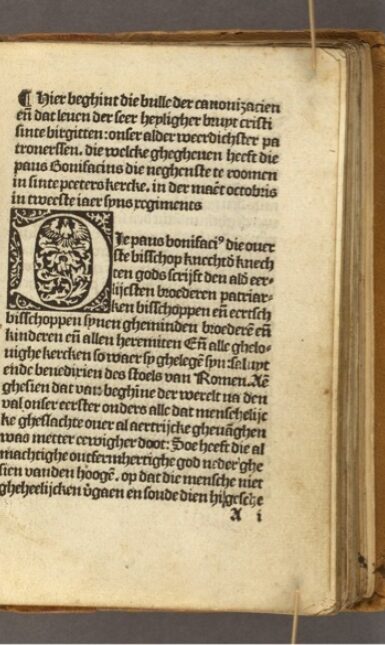

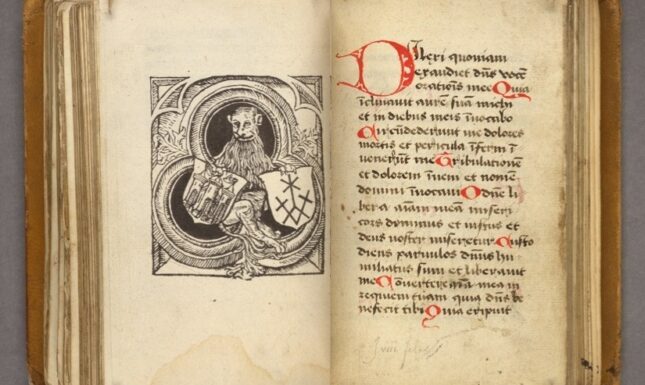

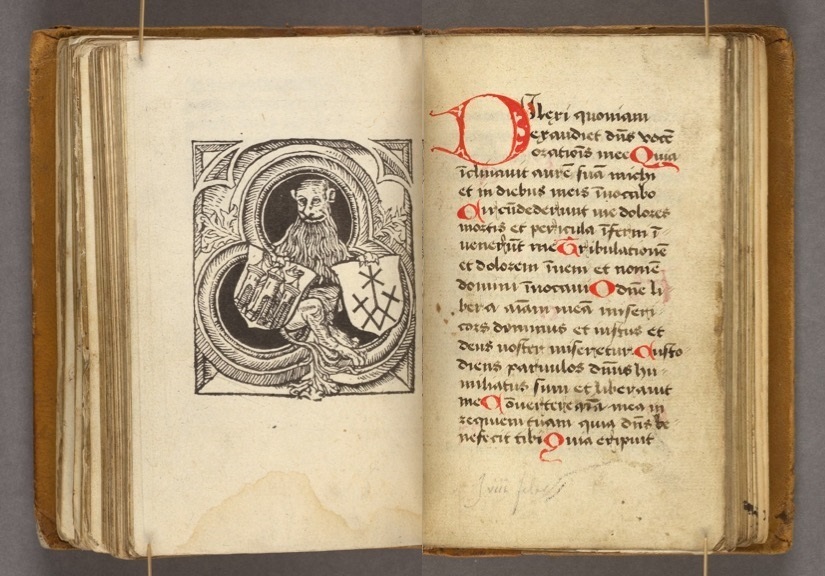

Comparing Latin and vernacular editions of a text can reveal extensive and deliberate differences (see e.g. Dlabacova 2021). In March 1489 the prolific printer Gerard Leeu published a Latin text on the life and Passion of Christ and his Mother taken from Saint Bridget’s Revelations. Jacob Canter, a humanist who hailed from Frisia, edited the Latin text for Leeu. Approximately two years later, Leeu published the text for a second time, now in Dutch (Fig. 4). The Dutch version was not only published on a larger, octavo format (instead of the sedecimo used for the Latin text), but even more strikingly, the additional texts that were included deviate substantially from those in the Latin edition.

In the Latin version, the text extracted from Bridget’s Revelations is followed by a legend of and prayer to Saint Bridget, and a prayer to Saint Catherine. The closing text is a letter written by Jacob Canter in which he addresses his sister Gebbe who lived in a Bridgettine convent and in which he exhorts the reader to meditate on Christ’s Passion. Conversely, the texts added to the Dutch translation of the text compiled from the Revelations include a papal bull on Bridget’s canonization issued by Boniface IX and the Life of Saint Catherine of Sweden (Bridget’s daughter). Why was the content revised? Were Latinate readers supposed to be already familiar with the canonization? Why was the exhortative letter left out of the Dutch edition? Did the Life of Saint Catherine hold special relevance for those who read in Dutch?

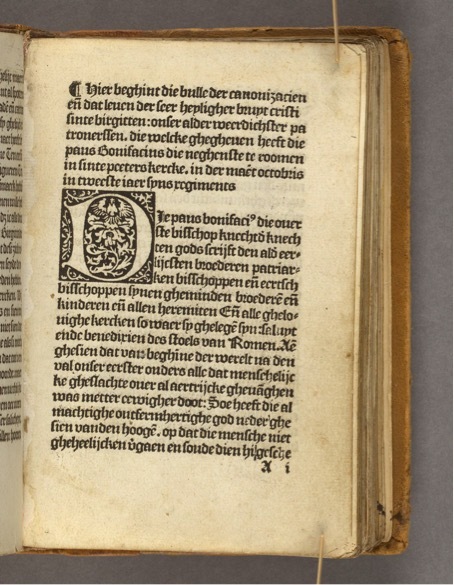

Crucially, the vernacular book is not a simple translation or derivative of the Latin edition. Indeed it presents a brand new text: the Life of Saint Catherine of Sweden in Dutch. The two books are more than ‘parallel editions’; the vernacular book is an independent publication with an apparently carefully considered collection of texts that was to serve a different type of reader. Precisely what type of reader, however, is difficult to establish. The heading at the start of the papal bull speaks of Bridget as ‘our most praiseworthy patroness’ [‘onser alder weerdichster patronessen’], which suggests a well-delineated readership among Bridgettine nuns only (Fig. 5).

The prologue at the start of the book, on the other hand, tells us that the text was extracted from the Book of Revelations ‘to exhort the hearts of Christian people to thankfulness for God’s gifts and blessings’ [‘om te verweckene die herten der kerstene menschen tot dancbaerheden vanden ghiften ende wedaden gods’]. Who, then, were the real readers of these texts? Since the few surviving copies contain limited evidence of the original readers, it remains difficult to draw conclusions. One copy of the Dutch edition was owned by a ‘Lysken Deckers’ (see Fig. 4) and is bound with Latin (prayer) texts written by hand (Fig. 6), which might point to female religious readers who read in Latin and Dutch. The market for vernacular books was thus by no means limited to the ‘illiterate’ who did not read Latin.

Mind the Reader?

The above indicates that reading in the vernacular could be a matter of preference or even of intellectual statement just as well as a matter of literacy. The care with which vernacular books were compiled and designed points to the development of a vivid and self-confident vernacular print culture from the late fifteenth century onward. Present-day scholars are increasingly ‘minding the reader’ as attentively as the early printers did. The combined study of printers’ strategies and readers’ traces offers a promising way to reconstruct premodern reading experiences.

Further Reading

- Dlabacova, Anna, ‘Volgens het boekje: Gerard Leeus Nederlandstalige editie van de Meditationes de vita et passione Jesu Christi’, Ons Geestelijk Erf 91 (2021), 109-157. https://scholarlypublications....

- Dlabacova, Anna, ‘Illustrated Incunabula as Material Objects: The Case of the Devout Hours on the Life and Passion of Jesus Christ’, in: Inwardness, Individualization, and Religious Agency in the Late Medieval Low Countries. Studies in the Devotio Moderna and its Contexts, edited by R.H.F. Hofman, C.M.A. Caspers, P. Nissen, M. van Dijk, and J. Oosterman. Medieval Church Studies no. 43 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2021), 181-221, https://doi.org/10.1484/M.MCS-EB.5.119395

- Leerdam, Andrea van, ‘Popularising and Personalising an Illustrated Herbal in Dutch’, Nuncius 36:2 (2021), 356-393, https://doi.org/10.1163/18253911-03602006

- Leerdam, Andrea van and Jessie Wei-Hsuan Chen, ‘Den groten herbarius: Healthy Herbs in Print’, 2017, https://www.uu.nl/en/utrecht-u...

- The family relation between Willem Barentsoen and Lambert Cornelisz Opsy is documented in P. Scheltema, Aemstel’s oudheid of Gedenkwaardigheden van Amsterdam, vol. 3 (Amsterdam: Scheltema, 1859), v–vi, 35–37; see also ‘Opsy’, in Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek, ed. P.C. Molhuijsen and P.J. Blok, 10 vols. (Leiden: A.W. Sijthoff, 1911–1937), vol. 5 (1921), col. 405–406.

- The conference on ‘Vernacular Books and Reading Experiences in the Early Age of Print (c. 1450-1600)’ will result in a volume, co-edited by Anna Dlabacova, Andrea van Leerdam and John Thompson, in the ‘Intersections’ series of Brill Publishers in 2022.

This blogpost and the conference are joint results of two NWO-funded projects: Anna Dlabačová's Veni-project ‘Leaving a Lasting Impression. The Impact of Incunabula on Late Medieval Spirituality, Religious Practice and Visual Culture in the Low Countries’ and Andrea van Leerdam's PhDs in the Humanities project ‘Woodcuts as Reading Aids. Illustrations and Knowledge Transfer in Printed Books in Dutch on the Natural World, c. 1480 - c. 1550’.

© Anna Dlabačová, Andrea van Leerdam and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Anna Dlabačová, Andrea van Leerdam and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.