Picture Perfect: The Life of a Fifteenth-Century Woodcut

Early printers often re-used their woodcuts. Previously created images could find new homes in a variety of texts. This post traces the life of a particular image that became the ideal image for the title page of a “love letter” from Christ.

A Love Letter from Jesus

During the last decades of the fifteenth century a “love letter” from Christ appeared rather suddenly in a number of printing shops throughout the Low Countries. Printers in Holland (Gouda, Leiden, Delft) and Antwerp published the text in small booklets: Christ’s epistle did not require more than six or seven pages, so one quire on the small octavo format provided more than enough space. As there are no manuscripts that predate the printed editions, Christ’s message does not seem to have enjoyed any previous circulation as a manuscript. While its origins are unclear, the love letter did enjoy widespread popularity while in press, with at least six incunabula editions (before 1501), the majority dated tentatively to the early 1490s, and almost all of them (five out of six) with a single extant copy only, which tells us that more editions to which no extant copies exist might very well have been created.

Why the sudden surge in the dissemination of this short text? Firstly, the text’s brevity made reproduction possible without large investments in paper or printing materials. Secondly, the text is animated and intimate. Christ speaks directly to the reader – imagined as an unfaithful bridewhore tired from the world only to become hooked on secular love letters and other worldly pleasantries. The sixteenth century saw at least five new editions of the letter and the epistle was also incorporated into a syllabus of ‘devout materials’ (Devote materien) published by the Regular Canons of Saint Michael in Schoonhoven (not far from Gouda), one of the Dutch printing presses run by a religious community. Most editions were produced in secular workshops. It is not surprising that these printers started adding images to the booklets to make their editions more attractive and possibly to avoid blank space.

Re-used…

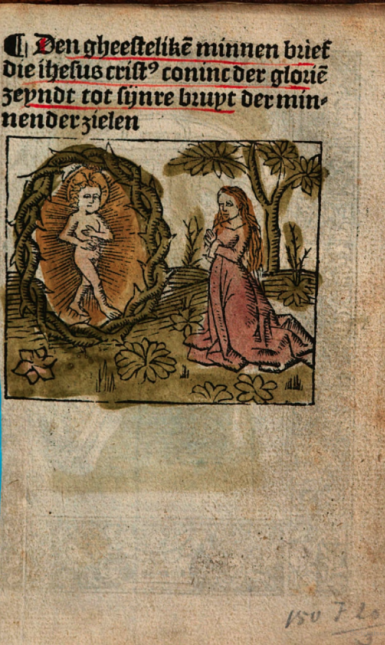

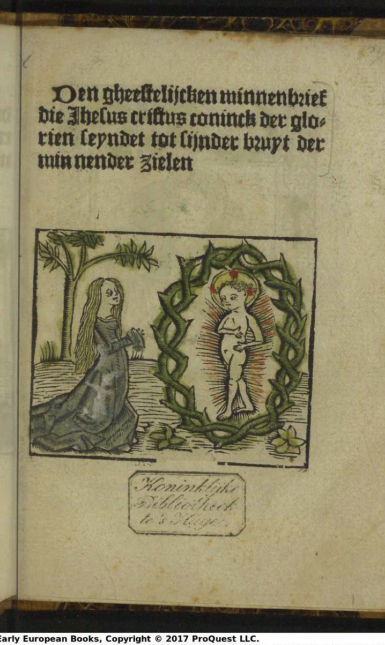

The prolific printer Gerard Leeu is said to have created one of the first editions with a woodcut image inserted below the title on the text’s first page (Fig. 1). We see what appears to be Christ’s ‘bride, the loving Soul’ on the right and the Christ Child surrounded by a crown of thorns on the left. This is odd since Christ does not present himself as a Child in the letter, but the crown of thorns reminds us of the Passion that plays an important role in his pleading with the Soul. One could also wonder why the Soul is kneeling in a praying position since Christ is the main actor who writes and sends the letter.

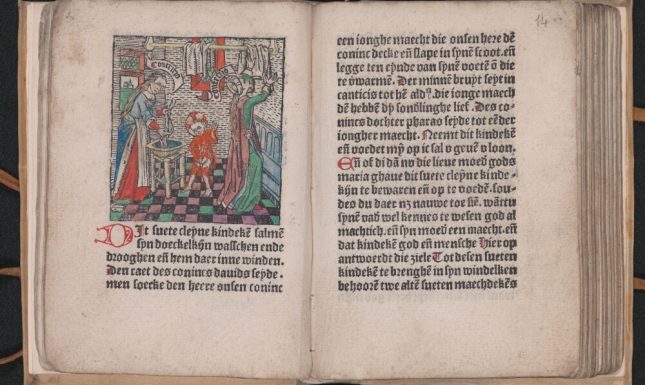

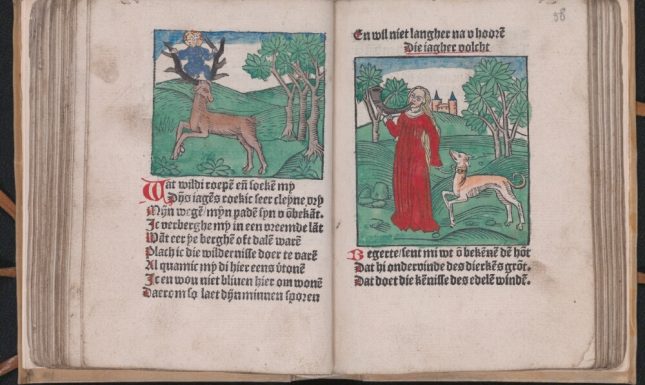

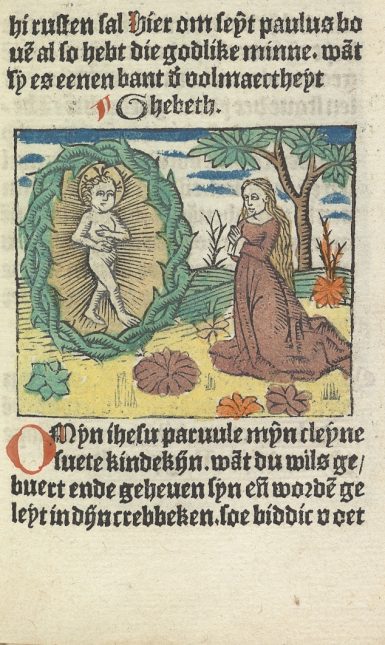

All possible inconsistencies can of course be explained by the fact that the printer re-used an existing woodcut. Originally the image was designed and cut for Leeu’s 1488 edition of a ‘trilogy’ in which the Souls nurtured and raised the Christ Child by way of virtues portrayed as ladies or virgins acting in pairs (contrition and confession, for example, wash Christ’s swaddles (Fig. 2)). Once the Child has grown up, however, he flees to his heavens. The Soul then hunts him down in a dialogue between her and the ‘deer’ Christ (Fig. 3). In the last section the Soul crucifies the grown Child by way of virtues, which portrays the process of reaching a mystical union. This is one of the most intriguing editions Leeu has published, and it combines a text previously transmitted in manuscript (the dialogue) with seemingly new texts. The woodcut used for the title page of Jesus’s love letter was originally made to accompany the prayers that follow each stage in Christ’s upbringing, found in the first section. In these prayers the Soul speaks directly to the Christ Child (Fig. 4).

…Re-cut, and Re-designed

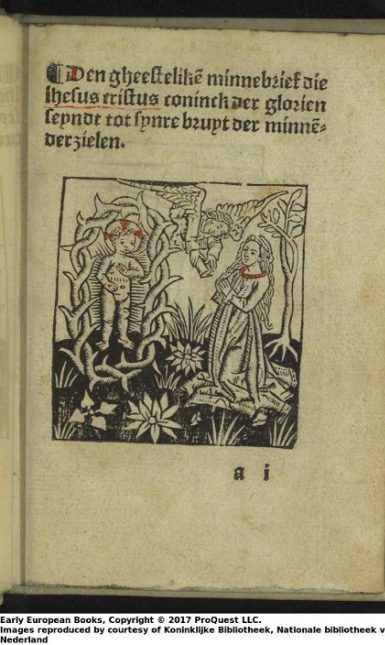

The only fifteenth-century edition of Christ’s love letter to which we can put an exact date is an edition published in Delft and ascribed to the printer Christiaen Snellaert. Printing finished on 10 August 1491. The title page of his edition contains an impression of a woodcut that appears to be an imitation of Leeu’s original (Fig. 5). Later still, around 1495-1496, the printer Govert van Ghemen, who previously published the love letter as text only in Gouda (tentatively dated between 1486 and 1492) and is by then working in the town of Leiden, employed a designer and/or woodcutter with more imagination. Or perhaps Govert himself, who already knew the text, directed the woodcutter to adjust the image so that it was more relevant to the contents and nature of the edition. We still see the Christ Child and the Soul, who looks more like a bride because of a diadem she is now wearing, facing each other, but the image displays a new dynamic: an angel, acting as Christ’s messenger,who hands ‘Christ’s bride the loving Soul’ the love letter that Christ wrote to her (Fig. 6).

Picture Perfect

After being re-used, re-cut, and re-designed, the image in van Ghemen’s edition is a picture perfect part of the title page and in sync with the edition as a whole. It portrays the origins of the text published in the edition and materializes the text by visualizing it as a physical letter in the angel’s hands. Rabia Gregory, seemingly unaware of the image’s previous life, argues in her 2016 book Marrying Jesus in Medieval and Early Modern Northern Europe. Popular Culture and Religious Reform that ‘The Christ child blesses her [the bride] as if he were not the bitterly disappointed author of the letter. Instead, the prefatory image’s prioritizing of the bride’s demure prayer, her knees touching the earth in a display of humility, and the Christ child’s tranquil gesture of forgiveness seem to show the end and the beginning of the story at once, as if to reassure the reader that the letter’s cause for complaint will be quickly corrected’. Gregory’s analysis further illustrates how Ghemen’s image fits the text perfectly. Finally, the life of this particular image shows that older texts inspired the iconography of new, unrelated texts through the work of printers.

© Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.