Pig Pharma: Some Uses of Swine in Early Medieval English Medicine

In early medieval England, pigs had a variety of uses. More than just something to put on a plate, pork also had medical properties, as this blog post reveals.

Animal medicine in antique and medieval medicine

The use of animal products in medieval medicine owes much to the legacy of classical antiquity, including the works of Galen and Pliny. The former had used dissection and vivisection of pigs to study matters of anatomy, while the latter, in his Historia naturalis, included many animal remedies including those that used pig’s gall, fat, feet and marrow, among other parts of the animal.

Some medieval medical compendia were fully devoted to the curative powers of animals. A clear example of such a compendium from early medieval England is the eleventh- or twelfth-century Old English translation of the Medicina de Quadrupedibus, a text which outlines how various parts of four-legged animals can be used to treat a variety of ailments. The text arranges remedies per animal and includes remedies derived from four domesticated animals, the goat, the ram, the bull, and the dog, as well as eight wild animals: the hart, the fox, the hare, the wild goat, the wolf, the lion, the elephant and the boar. The last animal in particular is the basis of some very effective medicine. The boar’s brain, for instance, is a panacea, a cure for everything:

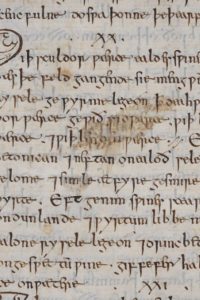

Wið ælc sar, bares brægen, gesoden 7 to drence geworh<t> on wine, ealle sar hyt geliðe gaþ. (Medicina de Quadrupedibus in London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius C.iii, fol. 80r)

[Againt every pain, a boar's brain, cooked and made to a drink in wine, with all pain it goes gently]

The text continues to list specific ailments that can be alleviated by other parts of the boar, including the lungs (for wounded feet), the liver (against stomach ache) and the bladder (against incontinence).

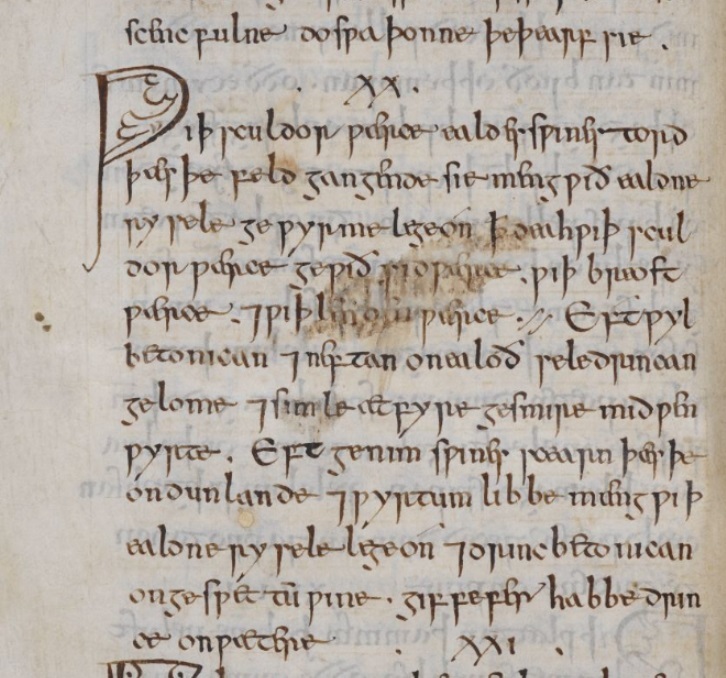

The curative properties of pig poo

Another element of medieval medicine that has its origins in classical antiquity is the so-called ‘Drekapothek’, the use of human and animal waste products (faeces and urine) for medical purposes. While the use of this material may seem counterproductive (as well as repulsive!) from a modern point of view, it is important to point out that the idea of bacterial transmission of diseases was unknown until the 19th century.

Among the boar remedies listed above, the Old English Medicina de Quadrupedibus advices those who suffer from erysipelas to rub the dung of a boar, mixed with sulphur, into wine and drink this draught frequently. Another Old English medical text, known as Bald’s Leechbook, outlines how the excrement of a pig, when heated, might be used as a poultice (or hot pack) against muscle sores:

Wiþ sculdor wærce, ealdes swines tord þæs þe feldgangende sie meng wið ealdne rysele, gewyrme, lege on. Þæt deah wiþ sculdorwærce ge wið sidwærce, wið breostwærce 7 wiþ lendenwærce.

[…]

Eft genim swines scearn þæs þe on dun lande 7 wyrtum libbe, mæng wiþ ealdne rysele, lege on 7 drinc betonican on geswettum wine.

(Bald’s Leechbook, London, British Library, Royal 12 D. xvii, fol. 23v)

[Against shoulder pain, mix the dung of an old swine that is walking in the field with old grease; warm it, lay it on; that is good against shoulder pain; side pain; breast pain and loin pain. … Again (against the same thing), take the excrement of a swine, that lives in a hilly area and among plants, mix it with old grease, lay it on and drink betony in sweetened wine.]

Interestingly, the notion that the excrement of pigs that live on fields should be treated differently than the manure of those pigs who live in a different terrain shows an awareness of how the diet of an animal may affect the contents of its dung.

Boar’s gall: An early medieval aphrodisiac

Another distasteful remedy involving elements of a pig is the following ‘aphrodisiac’ from the Old English Medicina de Quadrupedibus:

Weres wylla to gefremmanne, nime bares geallan 7 smyre mid þone teors 7 þa hærþan. Þonne hafað he mycelne lust. (Medicina de Quadrupedibus in London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius C.iii, fol. 80v)

[To carry out the desire of a man, take the gall of a boar and rub the penis with this and the testicles, then he will have great lust.]

This particular remedy may rely on a peculiar aspect of medieval medical texts: ‘sympathetic magic’, a type of magic based on imitation or correspondence. For instance, Bald’s Leechbook advices someone to sleep on the ashes of a burnt dog’s head in order to cure a head ache; if you have trouble retaining your urine, you should eat the bladder of a goat or a ram; and if you suffer from swollen eyes, just catch a live crab, put out its eyes and place its eyes on your neck. The cure, in other words, matches the disease or the desired outcome. Since pigs were associated with sexual lust (see this blog post: Pigs and Bagpipes: Geoffrey Chaucer's Miller in Context) it stands to reason that their gall could be lust-inducing as well.

The suspicion that this 'remedy' may have something to do with the boar's lustful reputation seems confirmed by the classical source for the aphrodisiac in the Medicina de Quadrupedibus: Pliny's Historia naturalis, book 28, chapter 80. Here, Pliny mentions the use of boar's gall as an aphrodisiac, along with other 'virile' alternatives, such as the testicles of horses and the urine of a bull. Pliny also mentions an 'antaphrodisiac': rubbing the groin with mouse-droppings. Clearly, it is the nature of the animals involved that gives these substances their peculiar powers to either raise or quell one's libido.

In today’s medicine, pigs continue to play an important role: the gelatine caps of pills are often made of pig-sourced gelatine, for instance, and insulin, heparin and glycerine may all be pork-based. As this blogpost has tried to show, this pig pharma is nothing new and has a long history, indeed!

Sources

- Pliny, Historia naturalis

- London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius C.iii

- London, British Library, Royal 12 D. xvii

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.