A medieval conspiracy theory: The murder of Little Hugh of Lincoln

This blog post shows that medieval tomb monuments, pilgrimages and funerary rites are not always as innocuous as they may seem, as they are sometimes connected to conspiracy theories about child murder.

This week, newspapers and other media in the Netherlands reported people laying flowers on childrens’ graves in the cemetery of Bodegraven, believing the buried kids to have been victims of ritual murder by a blood-thirsty elite. It is heart-breaking to see such falsehoods pop up in our country, especially when one realizes that such conspiracy theories, which originated in twelfth-century England, have long been debunked by scholarship, but have been retold over and over again, leading to tremendous human suffering and a great loss of lives.

The death of Little Hugh of Lincoln

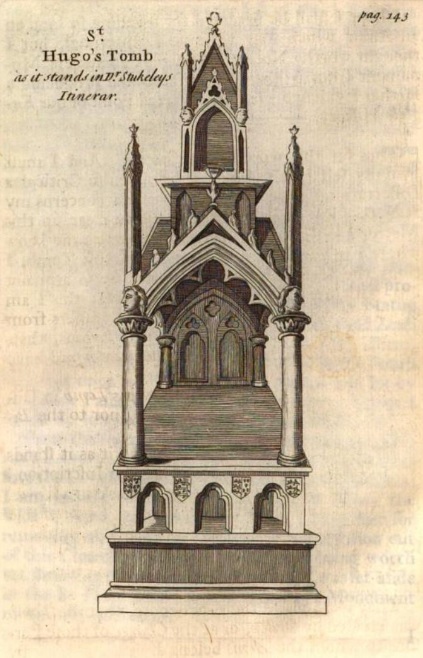

Along the choir enclosure wall, in the southern aisle of Lincoln cathedral are the remains of a monument erected for Little Hugh of Lincoln, a nine-year old child who was found dead in a well in 1255. Although he was never officially sanctified, his feast day was celebrated on 27 July. Due to the Reformation, when the cathedral was ‘miserably ravaged and desecrated by the Abhorrers of Idols, that not one Brass Plate or Monument escaped the rage of these Reformers’ (Dugdale, 1641), there is little left of the tomb monument. Only its base remains and there are scars in the wall where the superstructure was removed. An idea of what the tomb monument originally looked like can be had by means of a drawing by William Sedgwick in William Dugdale’s 1641 Book of Monuments (London, British Library Add MS 71474, fol. 108v), which was reproduced in print in many other publications. In its heydays, it was apparently quite a splendid affair and for this reason attracted the attention of various antiquarians.

Stylistic analysis of what little has survived, bears out that the monument dated from the early 1290s. Parallels with the very prestigious shrine built for the Crown of Thorns in the Paris Ste Chapelle have also been pointed out by scholars, indicating to what lengths its patrons went to stimulate Little Hugh’s cult. On its completion ‘they carried [his relics] aloft, proceeded by candles, crosses and thuribles, everyone in vestments, singing and weeping, to the proper, prepared and ordained place, to the great monastery of the Blessed Virgin, and together in sweet harmonious chords praised God’ (Annales de Burton). Up to the second half of the fourteenth century Little Hugh’s tomb performed well for the Lincoln chapter, bringing in a steady flow of cash.

The monument may seem a monument like any other, and there may seem nothing wrong with erecting a tomb for a small boy and stimulating pilgrims to come and visit, but there is more to Little Saint Hugh than meets the eye. His death was blamed on the Jews who were said to have sacrificially murdered the child, after first keeping him concealed in a cellar for a while. At the time of the Pesach feast, Jews from all over the country gathered in Lincoln and it was then, they said, that the child was mocked, as Christ had been, crucified, stabbed to death and disembowelled, for the purpose of their magic arts. The fully-fledged story of the murder can be read in the Chronica Maiora, written by Matthew Paris (†1259). It is believed that Hugh’s story was spread by local church officials hoping to start a lucrative pilgrimage and was subsequently approved by King Henry III who also stood to profit from it. Hugh’s story became the subject of songs and ballads.

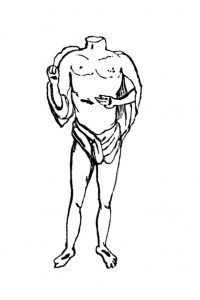

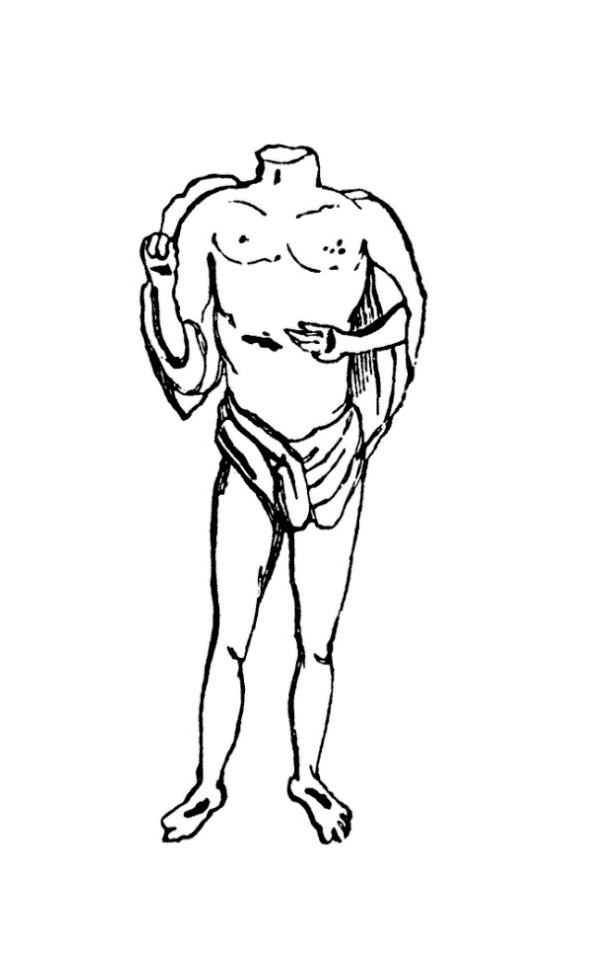

The repercussions for the Lincoln Jews were dire, nineteen of them were executed as a consequence of the false accusations, and many more imprisoned. And there was more to come. The erection of Little Hugh’s tomb monument in the early 1290s went hand in hand with the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290, providing justification for this radical measure. As D'Blossiers Tovey mentions in 1738, in his Anglia Judaica: Or the History and Antiquities of the Jews in England, the monument was even surmounted by a small stone statue of the saint, shown naked with the same wounds as Christ in his hands and feet, which he describes in detail, having rediscovered it in a dark passage behind the high altar of the church ‘covered in dust and obscurity’ (142). A drawing of this statue was made by the Antiquary Smart Lethieullier (1701-1760).

The long history of blood libel

The case against the Jews had been building up for quite a while. Initially, claims of blood libel impacted not the Jews but the early Christian community, as is apparent from the writings of Minucius Felix and Tertullian. In the second century AD, Christians were, amongst other things, accused of infanticide and devouring human flesh, drinking the blood of murdered children and performing rituals on their organs after disembowelment.

The antisemitic accusations of blood libel did not start until 1144, following the death of a small boy in Norwich (a religious centre that up to then had lacked a saint’s cult), who was said to have been crucified by Jews and when they had done with him, dumped his body in the woods. His cult developed from the 1150s onwards, when the monk Thomas of Monmouth penned down the earlier parts of his Life, Passion and Miracles of William of Norwich, a work that he continued until 1173. It was the earliest account of the alleged murder of a Christian child by a collective of Jews. In it, Thomas even claimed that every year, around Passover, Jews would capture a Christian child in order to torture and kill it.

Other accusations followed in 1168 (Harold of Gloucester) and in 1181 (Robert of Bury). Interest in these cults subsided with the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290, and even if not all blood libel accusations were credited or followed through, the damage was done and the tales continued.They even crop up in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in which the Prioress in the Prioress’ tale recounts a story of a Christian boy singing the hymn Alma Redemptoris Mater while passing through the Jewish ghetto on his way back and forth to school. In order to silence him, the Jews hired an assassin who slit the boy’s throat and deposed his body in a privy, where he was found a few days later, still singing the Alma Redemptoris Mater. The prioress concludes her tale by referring to the cult of ‘yonge Hugh of Lincoln, sleyn also With cursed Iewes, as it is notable, For it nis but a litel whyle ago’.

By the time the Jews were expelled from England, the blood libel fabrications had spread into France where the earliest example of such a claim occurs in the writings of Robert of Torigni, abbot of Mont-Saint-Michel, who mentions the Jews of Blois having been found guilty of murdering an unnamed youth by the local ruler Theobald of Blois in 1171.This was a blatant case of envy for the purpose of political gain, centring around Theobald’s mistress, the Jewess Polcelina, who had antagonised both Theobald’s wife and the local elite, who wanted her removed. Without a crime being established, even without a corpse or a named victim, 31 Jews were burnt at the stake, including the said Polcelina and her daughters. The other Jews of Blois were either imprisoned or forced to convert. Antisemitic tales of blood libel also spread to other European countries. In Germany we have sixteen-year old Werner (1267), in whose honour chapels were erected in Bacharach and Oberwesel, and in Italy there is Simon of Trent (1475). And these young children were by no means the last to have allegedly been murdered by Jews. Adapted and expanded, such antisemitic falsehoods continued to be reiterated, century after century, feeding the popular imagination, producing a whole series of martyred child-saints and feeding antisemitism.

The afterlife of a medieval conspiracy theory

A lot has been written about these damaging medieval blood libel accusations directed at the Jewry, on how these false accusations were driven by greed and envy, and on how these lies impacted the Jewish community, eventually leading to the murder of millions during the Second World War. And still these stories flourish, even experiencing a revival in recent years. Remember Pizzagate in 2016, when a deluded gunman targeted the Comet Ping Pong Pizzeria in Washington D.C., that had already been harassed for weeks, believing that small children were being held in its cellars by the so-called Cabal to be abused and ritually murdered. As a matter of fact, there were not even cellars, as the gunman found out to his great surprise. The story of the children held in the cellar in order to be murdered is remarkably like the one circulating about Little Hugh of Lincoln, thus perpetuating a shameful thousand-year old story that cost many Jews their lives and that has long been proven untrue. And it continues. As mentioned, over the past few days the cemetery of Vredehof in Bodegraven has made national headlines, flowers having been laid at the graves of young persons buried there, by people who, misled by conspiracy theories posted on the internet, hold that these young people were murdered at the behest of a satanic elite intent on drinking their blood.

Although theories like the ones that have recently surfaced in the Netherlands come directly from America where supporters of QAnon spread tales of Democrats misusing and murdering children, sadly but true, their ultimate origins lie in the medieval past. In Lincoln, as shown,there is even a monument to attest to this ugly truth. Today, of course, there is a plaque next to it explaining the story of Little Hugh of Lincoln and the terrible treatment of the Jewry in thirteenth-century England, but the story having been set loose in the world, Pandora’s box can no longer be closed. The lies of old continue to impact the present as old tales are resilient, in spite of having been proven wrong. The malicious falsehoods of the past will be perpetuated as long as there is a will to ‘other’ others, feeding on general feelings of ‘angst’ in times of insecurity, and to victimize an imagined enemy for financial or political gain.

Select Literature:

Thomas of Monmouth, The Life and Passion of William of Norwich , ed. and transl. M. Rubin, Penguin Books 2014.

John Crook, English Medieval Shrines, Woodbridge 2016.

Hannah R. Johnson, Blood Libel. The Ritual Murder Accusation at the Limit of Jewish History, University of Michigan Press 2012.

David Stocker, ‘The Shrine of Little St Hugh of Lincoln’, Medieval Art, and Architecture at Lincoln Cathedral (Proceedings of the British Archaeological Association Annual Meeting), London 1982, 109-17.

B. Wagemakers, ‘Incest, Infanticide and Cannibalism: Anti-Christian Imputations in the Roman Empire’, Greece & Rome Second Series 57-2 (2010), 337-354.

© Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.