Rumi and the Hollywood Stars: The Source of Brad Pitt’s Tattoo

It is almost hard to find a celebrity without a tattoo, but why should the tattoo be from a Persian mystic poet from the thirteenth century? How should we look at such texts?

Brad Pitt’s Tattoo

The text on Brad Pitt’s arm runs as follows, “There exists a field, beyond all notions of right and wrong. I will meet you there.” These words are characterized as a ‘romantic poem’ tattooed prior to his wedding with Angelina Jolie. Or as another website has it, “The tat might reference Pitt’s social justice work or, as was often the case with the ecstatic Rumi, encapsulate the wild freedom and transcendence of a passionate love.”

To my knowledge, a few people have attempted to explain the original poem on internet. Ibrahim Gamard examines the translation, which is inspired by Colman Barks’ version, on how the poem is “divested [...] of its Islamic content,”. And Brad Pitt himself is quiet about this aspect of his personal life. If Brad Pitt wants to know the source, here comes the poem in the original Persian and my literal translation. Of course there are many other (more liberal or poetic) translations:

از کفر و ز اسلام برون صحرائیست

ما را به میان آن فضا سودائیست

عارف چو بدان رسید سر را بنهد

نه کفر و نه اسلام و نه آنجا جائیست

Outside unbelief and Islam, there is a desert,

In the midst of this space we have longed for love.

When the mystic arrives here, he lays down his head,

As here there is no place for either unbelief or Islam.

Rumi and his Popularity

The Persian mystic poet Jalal al-Din Mohammad ibn Balkhi better known as Rumi (1207-1273) is a best-selling poet in the United States. Demi Moore, Madonna, and recently Beyoncé are all his admirers. His popularity in the English speaking world is due to Colman Barks’ translations. Barks does not translate Rumi’s poetry from Persian but bases himself on previous translations in such a way that Rumi speaks to people of all walks of life irrespective of their ethnic and religious backgrounds. Beyoncé’s and her husband Jay-Z’s admiration for Rumi are so boundless that they even named their son Rumi.

What is the appeal in Rumi’s personality and poetry? There is a wide range of reasons one can think of. To begin with, in his poetry he expresses wisdoms for a peaceful life in this world and a blessed life in the hereafter, teaching his readers to transform even the most painful experience into a gift.

Love is a central subject in his poetry, which even transforms pain and suffering into love. Rumi is perhaps one of the world’s most prolific poets having composed some 120.000 lines of poetry, covering a rich array of subjects. His masterpiece Masnavi is called the Koran in the Persian language as he unravels the meanings of the Koran for ordinary Muslims wrapped in splendid anecdotes and theoretical explications. Several of his lines and anecdotes are deeply ingrained in the minds of Persians such as his opening lines about the complaint of a reed cut from the reedbed, singing its song of separation and its longing to return to the original home. A perfect metaphor for the soul of man craving to return to the primordial abode. The metaphor is also often used by millions of refugees expressing their aborted states and their longing for their homeland.

Another reason for his popularity is that many people see in Rumi a tolerant and humanist Muslim, who uses metaphors of drinking wine, homo-erotic love, and even prefers the wine-house over the mosque. Rumi is indeed is a follower of antinomianism, which is so much part and parcel of Persian mysticism. Antinomianism is a movement that questions outward piety, where people obey rules and norms, but without inward sincerity.

Antinomian philosophy is epitomized by the character of the qalandar, a wandering dervish. These qalandars questioned concepts such as piety, generating discussions of who is a good Muslim? Is a good Muslim a person who wears a long beard and goes to the mosque, showing his religiosity? Or a person who loves God in his heart but drinks wine in a tavern. These qalandars were essentially very pious and were afraid that any outward show of piety would generate respect from the society, any outward respect would be a pitfall on the mystic path, which they had to avoid at any costs. They believed that public respect would lead to hypocrisy. Therefore they flouted all religious and social norms and values by shaving their facial hair, drinking wine publically and showing themselves (half-)naked on streets.

During Rumi’s time the qalandari philosophy was very popular. His beloved friend Shams from Tabriz was a qalandar Sufi who entirely transformed Rumi from a theologian to a mystic poet. Part of modern reception of Rumi has to do with the unorthodox character of the Qalandar and the way they looked at religiosity and piety.

The Message of the Quatrain

The quatrain cited above describes a plain or ‘space’ outside our conceptual world, beyond conventions and religion where one can freely contemplate love. The poet goes beyond the boundary of predicates such as good and bad, Islam and heresy. There are hundreds of poems like this one by Rumi in Persian literary traditions. Mystic poets employed such motifs, themes and imagery to create ‘space’ for several reasons. They reacted against theologians by offering love as the sole medium to reach God, and at the same time this space is ambiguous enough to contemplate any subject. It is often said that Islam does not have the capacity for self-criticism or self-reflection, but in this qalandari genre in Persian poetry the most holy tenets of Islam are discussed and evaluated. Temporary concepts such as Islam and heresy are limiting and are related to outward realities of religion.

One wonders why Brad Pitt tattooed this sentence on the right arm. Is it because of Rumi’s popularity as a humanist poet in the United States, or the playfulness of our contemporary culture? While this tattoo shows how Persian poetry is translated for a broad public in such a way that it is far from the original meaning, it also demonstrates Pitt’s playful behaviour, a ludic way to show appreciation of great minds such as Rumi.

How to Deal with the Reception

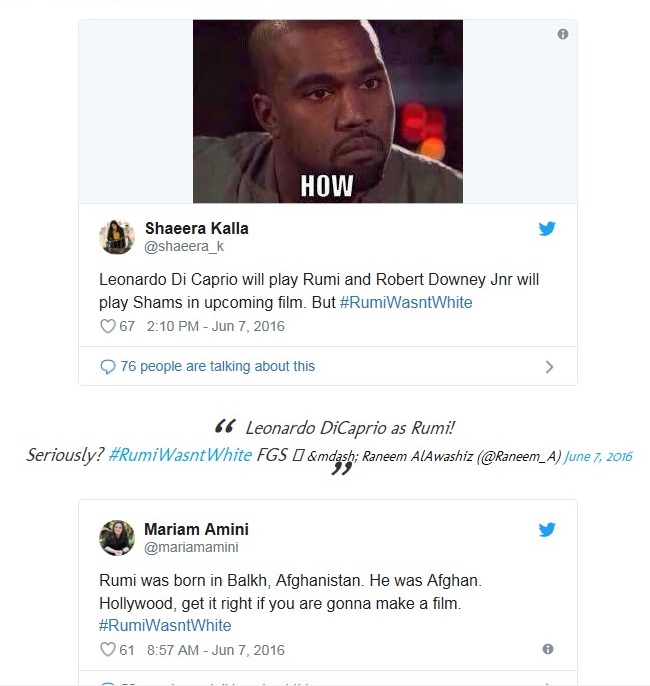

The question is how we as scholars of Religious Studies and Literary Studies should respond to the reception of Rumi’s mystical poetry in such a context? The fact that a Hollywood star has tattooed Rumi’s words on his body brings some Persian speaking people into ecstasy as it offers a sense of appreciation of Persian culture in the West, while others would be disappointed to find out how Rumi’s message is maimed to serve a broad public. Rumi was a pious Muslim but in several popular translations his Islamic identity is reduced or even removed. The literary sophistication is lost and the historical contextualization is absent. Personally I stick to the original not only for the sake of splendid poetic superiority, but also to understand Rumi and his philosophy by studying his own time. I admit that responses to such receptions are fascinating, especially when we look at Social media discussion around the announcement about a movie in which Leonardo DiCaprio was suggested to play Rumi and Robert Downey Jr. as Shams of Tabriz. In such a context, classical Persian poetry creates much room in which race, nationality, and religion are discussed. Irrespective of the differences in cultural backgrounds, religious affiliations, political views, and nationality, for Rumi love remains the leading principle of life.

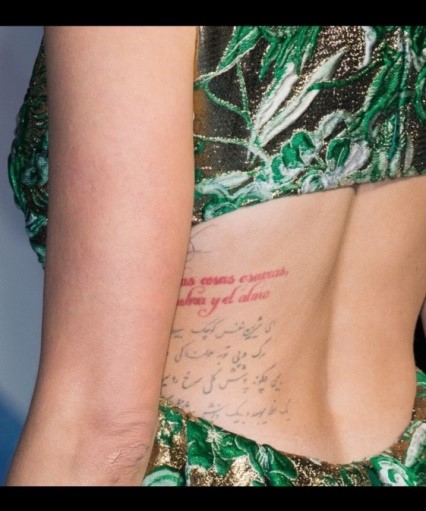

Brad Pitt’s tattoo is not an isolated case, as other Hollywood stars have also placed Persian poems on their bodies. Amber Heard tattooed a whole quatrain on her waist. In Jimmy Fallon show, she said that the poem belonged to Omar Khayyam but I could not find such a poem in famous collections of Persian quatrains. While in Pitt’s line, the meaning of the poem is intriguing, here the aesthetics of elegant Persian script in blue is on the show.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Brad Pitt’s tattoo is that it generates discussions about our globalizing culture in which playing with world’s cultural heritage becomes more and more central. With the use of such texts, whatever their translations and their sources may be, the religious and national boundaries change in a playful fashion to puzzle readers.

Further reading

For an excellent study of Rumi, his life, work, and teaching see

-Lewis, F.D. Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rūmī. Oxford: Oneworld 2000.

For Rumi’s translations see

-Lewis, F.D. Rumi: Swallowing the Sun: Poems Translated from the Persian. Oxford: Oneworld 2008; repr. 2013.

-Rumi. Spiritual Verses: The First Book of the Masnavi-ye Ma'navi. Trans. With an Introduction and Notes by Alan Williams, Penguin Classics, 2006.

All of Rumi’s quatrains are translated by Ibrahim Gamard and Rawan Farhadi:

-Rūmī, Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad. The Quatrains of Rūmī, trans. Ibrahim Gamard and Rawan Farhadi. San Rafael, CA: Sufi Dari Books 2008, for an alternative translation see p. 407.

For Rumi’s antinomian philosophy see

-Seyed-Gohrab, Asghar, “Rūmī’s Antinomian Poetic Philosophy,” in Mawlana Rumi Review, (Forthcoming 2019).

For the reception of Persian poetry see

-Yohannan, J. D., Persian Poetry in England and America: A 200-Year History. New York: Caravan Books 1977.

© Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.