Singing along in the margin

In the early medieval books of Fleury, neumes (an early form of music notation) are a regular occurrence in the margins. Who wrote these neumes and why?

The edges of the page

Several recent contributions of the Leiden Medievalists Blog (A new reading of medieval ‘doodles’ - Leiden Medievalists Blog; A World in the Back of a Book - Leiden Medievalists Blog) have drawn our attention to aspects of the medieval manuscript that are not part of the main text, in the middle of the page, but rather at its edges. I myself have spent quite a lot of years of my academic time to the study of the periphery of the medieval manuscript, to wit the margins, flyleaves, reader’s annotations, traces of use or ownership, et cetera. It has resulted in a digital edition, a dataset and even an online exhibition, in addition to books (Teeuwen & Van Renswoude 2017) and articles. On all of these research endeavours I was (fortunately) not alone, but accompanied by fellow researchers who collaborated with me and greatly contributed: I mention here Irene O’Daly, Irene van Renswoude and Evina Stein by name as the most obvious ones – in alphabetical order –, and there are many more!

For this blog, I would like to draw attention to a marginal phenomenon which has remained unseen for many years: the notation of music and melodies in the margins. Being a musicologist by academic birth, I was struck by this type of marginal annotation and wondered how to interpret it. Examples are easy to find: recently I was researching ninth-century books of Fleury (of which Leiden University Library happens to have quite a few), and music notation popped up in almost every book I studied. Sometimes the music was clearly connected to the text: when the text mentioned saints, for example, for whom songs were performed in the liturgy. But more often the melodies were unrelated to the text in the middle of the page. So, I asked myself the question: who wrote them down and why?

Early music notation

In order to approach this question, a bit of background information about music notation in the ninth century is necessary. The earliest music notation is known as neumes and has the shape of tiny squiggles: strokes, dots, arched or twisted lines. They indicate the number of pitches on a single syllable (one, two or more in one sign) and the general direction of the melody: is the melody going up or down, or does it stay at the same pitch? In the earliest phase of music notation, this is all. No information is included about precise pitch, tempo, relative length of the note or relative pitch. Thus, for example, a specific neume sign called scandicus tells us that a melodic unit consists of three notes that start low and go up and up, but we don’t know whether this is in the fashion of do-re-mi, re-fa-sol, or do-mi-sol, et cetera. Information of this more precise kind was integrated in the music notation system only later in the middle ages.

In the manuscripts of ninth-century Fleury, we find music notation of this early kind. The books were made by or owned and used by the monastic community of Saint-Benoît sur Loire, in the Loire valley. The abbey was one of the most important benedictine monasteries of the early Middle Ages, especially after the transfer of relics of Saint Benedict to the monastery in 672. Powerful abbots ruled the monastery, most notably the Spanish monk and scholar Theodulf, who was part of Charlemagne’s entourage and became bishop of Orléans in 798. The books that survive of the monastery show us the portrait of a rich intellectual centre, in which both religious and secular books were produced in sizeable quantities (Mostert 1989).

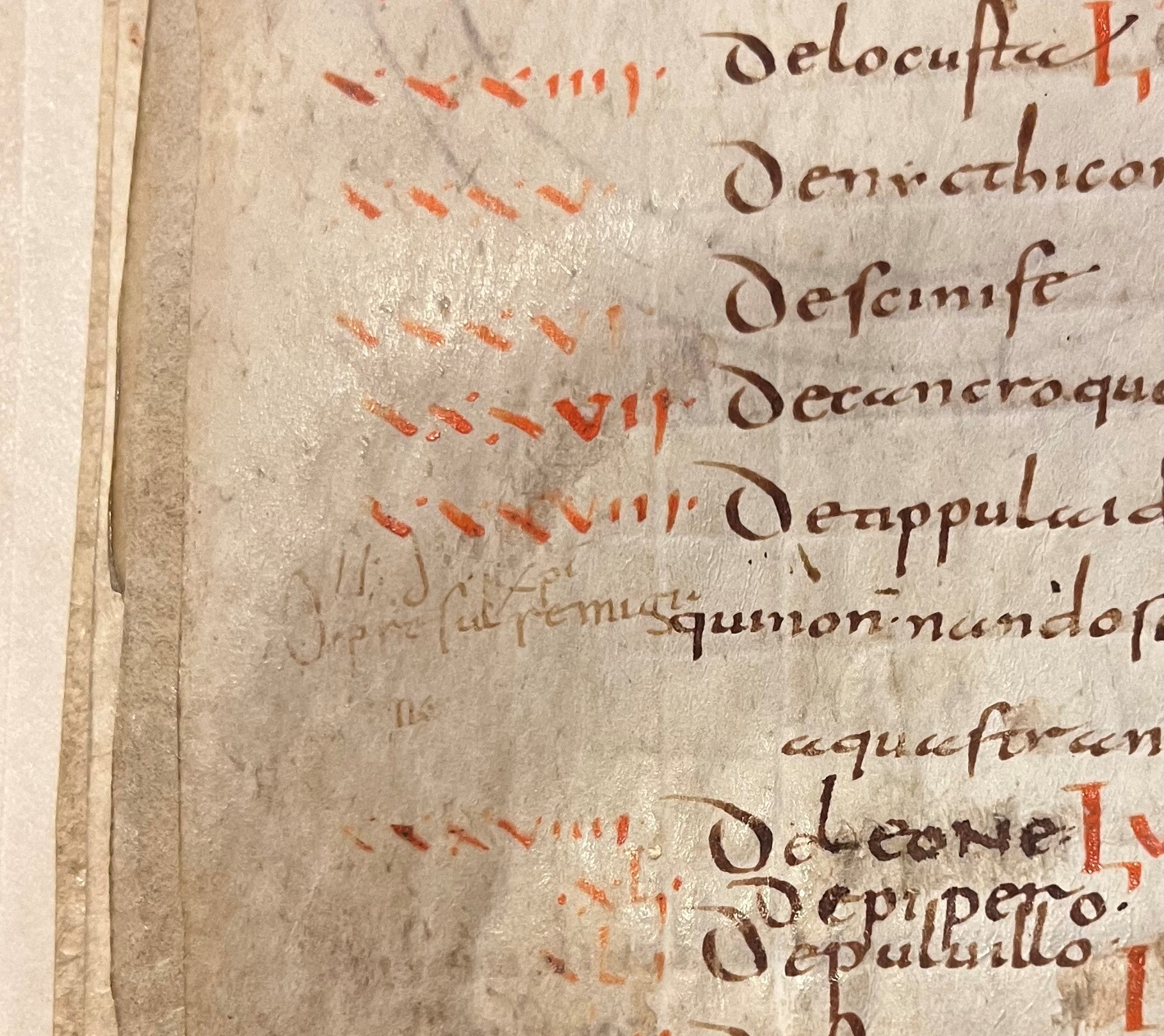

Leiden, UB, VLQ 106

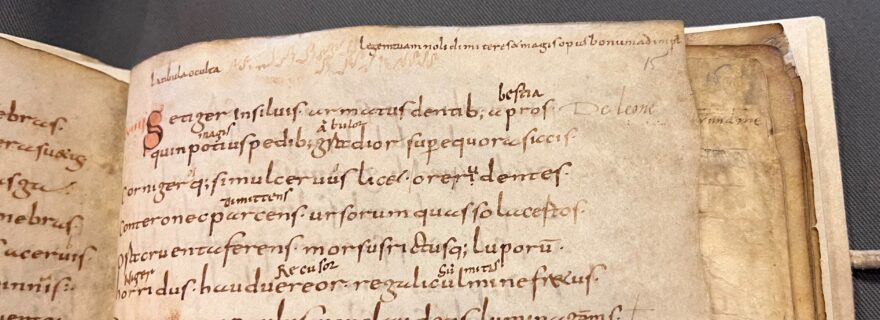

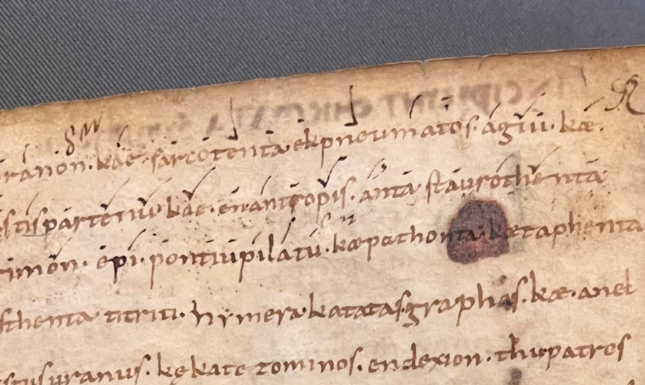

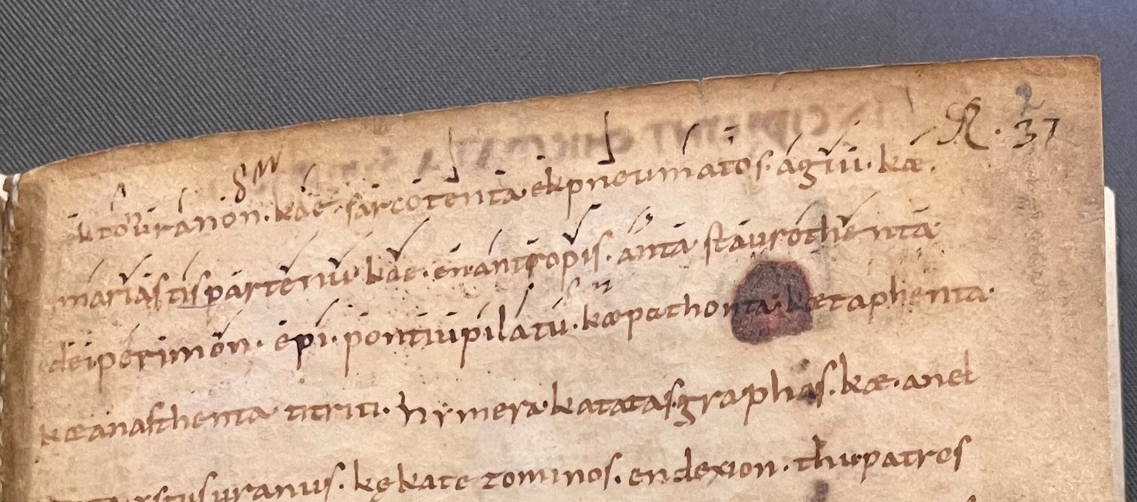

The music that pops up in the marginal and interlinear spaces of these books is remarkable. I show here just one example: Leiden, UB, VLQ 106 (available in Codices Vossiani Latini Online). In this book we find neumes from at least five different hands. Some note down a melody, either to the text in the middle of the page or in the margin. They were written over a text. On the originally empty page fol. 2r, for example, we find neumes over a Greek text, written in Latin script: “ek ton uranon kae sarcotenta ek pneumatos agiu kae | marias tis partenô kae enantropis anta staurothenta | de iper imon epi pontiu pilatu kae pathonta kai taphenta” (a passage from a letter of St. Basil the Great). [Figure 2]

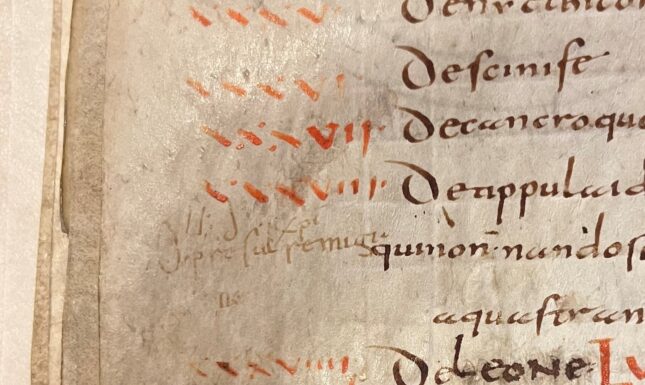

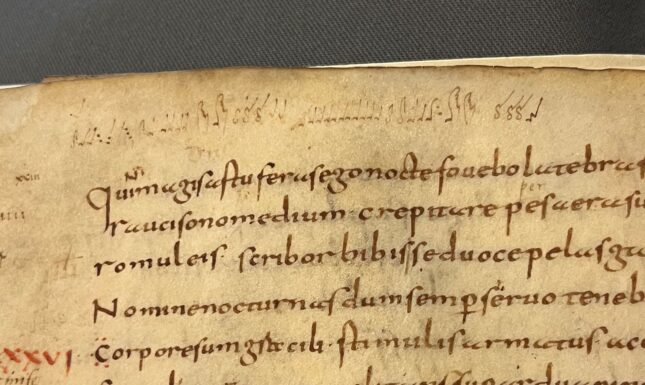

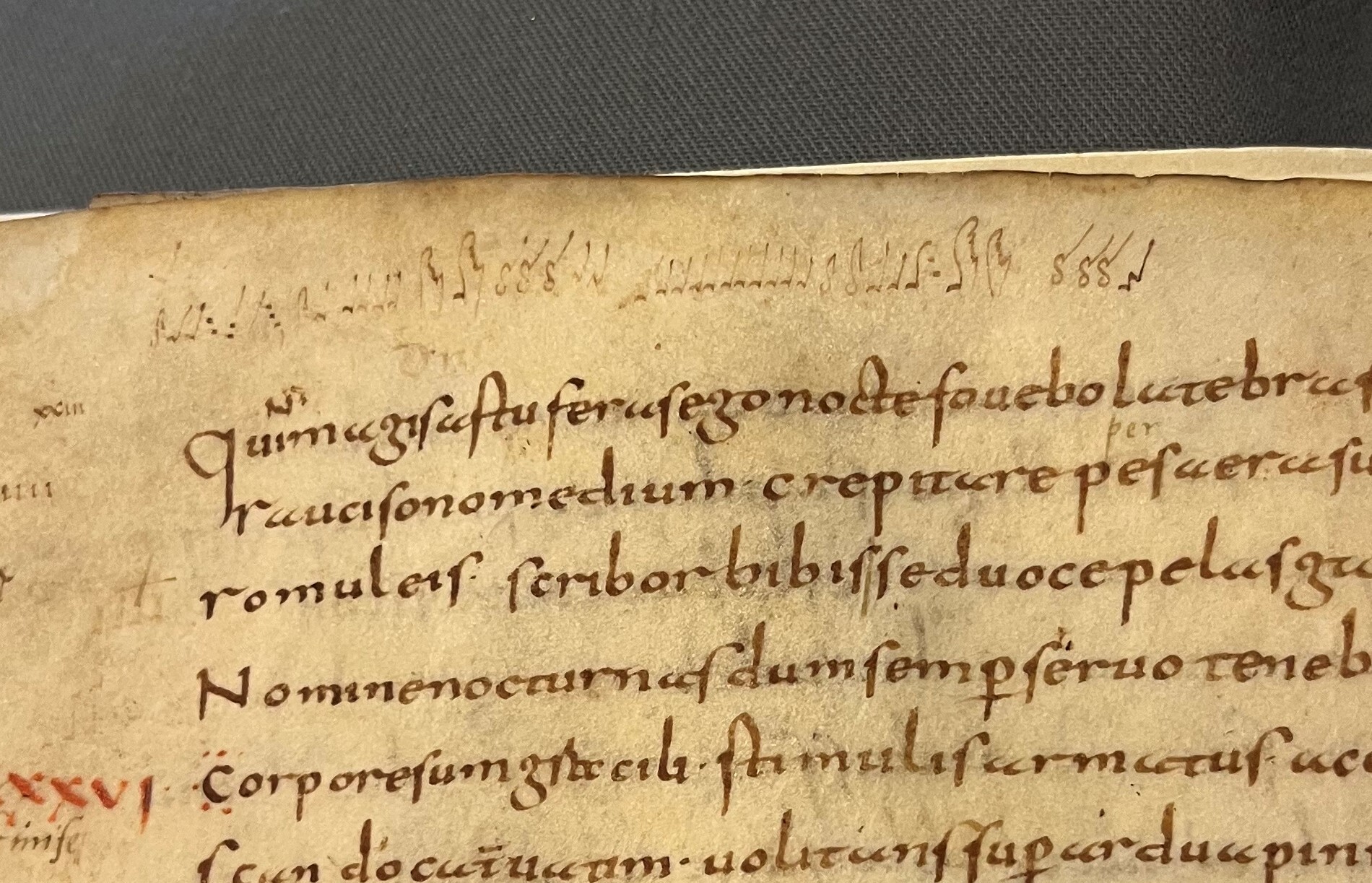

In a different hand, a monk notated a melody in the margin of fol. 9 verso: the opening of the responsory “O presul Christi remigii”. [Figure 3]

Yet another hand is found at the top of fol. 14v, but in this case there is no text. [Figure 4]. If we look carefully at the series of signs, moreover, we see that some signs are repeated multiple times. This is probably not a melody, but rather an exercise: the scribe is practicing the writing of different shapes, such as the podatus (looks like an mirrored capital L), torculus (looks like an S with an upward line) and quilisma (a quivering line).

Humming scribes?

I could continue giving examples from just this manuscript alone, but I would rather return to my opening question: who wrote these neumes and why? In order to interpret the presence of the neumes it is important to know that the melodies have nothing to do with the main texts in the manuscript: these are late-ancient riddles from the collection of Symphosius (ff. 2v-8v), and a seventh-century collection of riddles by Aldhelm (ff. 8v-25v). Some of the neumes can be identified as added liturgical melodies, some are unidentifiable melodies without texts. There are also series of neumes that do not seem to form a melody, but suggest a writing exercise: to practice the writing of neume shapes fluently and consistently. Or, perhaps, they were made to test a newly cut pen or a new batch of ink. The delicate shapes of neumes may have been excellent material to try this out.

The answer to the question “who wrote them?” must be the monks who were engaged in the task of copying books, or who were working with the books. They did this with a pen in hand, in order to correct them or add materials to them that was deemed important. In the Rule of Saint Benedict, which guided the daily routines of the brothers of Benedictine monasteries such as Saint-Benoît sur Loire in Fleury, the activities of reading and writing (that is: copying) were firmly established. The production of books was necessary to give the monastery a library that would support an exemplary Christian life and the performance of daily (chanted) prayer. The margins, furthermore, testify of a culture of writing in which copyists, readers and students were free to add material to the books they handled, albeit to a limited extent.

The squiggles we just discussed paint a vivid picture of a monastic community whose scribes had the writing of neumes as a basic skill in their toolbox – not just a single specialist scribe, or a few, but numerous hands can be found to write neumes in this book over an extended period of time. The quantity of witnesses, moreover, seems extraordinarily large: I found them in surprisingly many of the Fleury manuscripts. But a systematic investigation of neumes in margins has not been carried out, so we lack the data to compare in a reliable way.

The question “why did they write them?” is more difficult to answer. My Utrecht professor Kees Vellekoop, expert of medieval music, instilled in us: monks were singing almost non-stop. Every three hours of each 24-hours, they performed an office in which all texts had melody, from simple recitation formulas to elaborate and intricate melodies. If I were allowed to fantasize (and who stops me from doing that in a blog!), I imagine a community in which the heads of those who made, handled and studied the books were filled with melodies, so much that they happened to flow out of them right onto the edges of pages.

Further reading

On Leiden, UB, VLQ 106:

K.A. De Meyier, Codices Vossiani Latini, Pars 2: Codices in Quarto, Leiden, 1975, 235-237.

On the manuscripts of Fleury:

M. Mostert, The Library of Fleury: A Provisional List of Manuscripts, Hilversum: Verloren, 1989.

On early music notation:

S. Rankin, Writing Sounds in Carolingian Europe: The Invention of Musical Notation, Cambridge Studies in Palaeography and Codicology, Cambridge: CUP, 2018.

On practices of annotating books:

M. Teeuwen & I. van Renswoude (eds.), The Annotated Book in the Early Middle Ages: Practices of Reading and Writing, Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy vol. 38, Turnhout: Brepols, 2018.