Snatched by the wind: The wooden chapel of Saint Servatius in Maastricht

A wooden chapel dedicated to St. Servatius in sixth-century Maastricht has gotten a bad press. Historical and archaeological comparisons may redeem this humble shrine and illuminate the darkest years of post-Roman towns.

In a previous blog, I discussed the survival of urban life in Cologne after the Roman period. New evidence brought to light by archaeology, as well as reconsideration of old evidence, is starting to challenge the idea of a total collapse of towns in the early medieval west. A similar story might be told by a single church from Maastricht: the Basilica of Saint Servatius.

The church is still an impressive sight to behold, with its beautiful Romanesque architecture going back as far as the eleventh century. Far older than that, the church was first mentioned in a sixth-century miracle story by Gregory of Tours. According to Gregory, the local bishop Monulphus replaced a flimsy wooden chapel (oratorium) at the tomb of St. Servatius with a magnificent stone church or templum magnum around the middle of the sixth century. Scholars have usually paid more attention to Monulphus’ stone temple, but the wooden chapel that he replaced is just as interesting for what it can tell us about the earliest years of post-Roman Maastricht.

Romanesque exterior (partially 11th-12th c.) of the Basilica of Saint Servatius in Maastricht. Source: Wikimedia.

Servatius' tomb

Maastricht was strategically situated where the Roman road from Cologne to Amiens, the important Via Belgica, crossed the river Meuse. [1] Probably for this reason, a fort with bridgehead was built here under emperor Constantine (308-337), roughly in the area of the current Basilica of Our Lady. In the fourth century, the local bishop Aravatius (presumably the same person as Servatius) still resided in the nearby town of Tongeren. However, as Gregory tells us, one day Aravatius/Servatius tearfully bade farewell to his clergy and the citizens of Tongeren and departed for Maastricht. Once there, he died from a fever and was buried beside the Roman road just outside the fort (Histories, 2.5).

Afterwards, the place of his death seems to have attracted the attention of the local faithful, who built a wooden chapel to commemorate his grave:

"Although snow fell around his tomb, it never moistened the marble that had been placed on top [of the tomb]. Even when these regions were gripped in the cold of the excessive frost and snow covered the ground to a thickness of three or four feet, the snow never touched his tomb […] Many times the devotion and zeal of believers have constructed an oratory (oratorium)

from wood planks that had been planed smooth; but immediately the planks either are snatched by the wind or collapse of their own accord. And I believe that this continued to happen until someone came along who constructed a worthy building in honour of the glorious bishop. After some time had passed Monulph[us] became bishop of Maastricht. He built, arranged, and decorated a huge church (templum magnum) in honour of Aravatius. His body was translated into this church with great zeal and veneration, and it is now distinguished with great miracles".

- Gregory of Tours, Glory of the Confessors, 71, transl. Van Dam p. 52-53.

Gregory’s description of the wooden chapel is not very flattering, conjuring up the image of a rickety structure hardly fit for the harsh climate of northern Gaul. By extension, Maastricht around the year 500 seems no more than an insignificant backwater until Monulphus graced it with his stone church. However, there are good reasons not to take Gregory’s hyperbolic account at face value.

A view from the Loire

Gregory was not a local. As his name implies, he was bishop of Tours and born in Clermont-Ferrand, far to the south of Maastricht. While early medieval Limburg may have been somewhat colder than in today’s age of global warming, Gregory’s description seems a literary exaggeration that played to his audience’s expectations. The frosty narrative is more in tune with stereotypes from classical Roman literature which depicted northern Gaul as the inhospitable edge of the world.

Closer to home, Gregory is far less negative in his description of wooden sanctuaries. In one amazing story, a Parisian man had built an oratory in wattle-work on top of the city gate where St. Martin had cured a leper. When a fire swept over Paris, the whole neighbourhood was turned to ashes, but miraculously the humble shrine was spared (Histories, 8.33). The construction of this oratory sounds far less refined than the one in Maastricht built with planks, yet Gregory’s judgement is far loftier. Probably in no small part because St. Martin was his patron saint.

He also mentions other wooden churches built with planks, such as another shrine to St. Martin on top of a city wall in Rouen (Histories, 5.2), or a shrine near Limoges housing the relics of the martyr Georgius (Glory of the Martyrs, 100). In the territory of Clermont-Ferrand, a group of monks carrying the relics of St. Saturninus lodged for one night in a peasant’s house. The place was made holy by the presence of the saint’s relics, and so afterwards the peasant tore down his own cottage ‘to build an oratory out of wooden planks’ (Glory of the Martyrs, 47). In the nearby village of Thiers there was another church built with wooden planks, containing a holy altar with a silver reliquary of St. Symphorianus. It was burned down by soldiers, but the reliquary miraculously survived (Glory of the Martyrs, 51).

On a closer reading of Gregory, it seems that many churches in Merovingian Gaul were built out of wood. None of these timber shrines were blown away by the wind. Indeed, they were sometimes important enough to hold holy relics.

Traces in the soil

Archaeology now confirms this picture. Dozens of wooden churches from the Merovingian period have been excavated over the last few decades. In Pontarlier (France), archaeologists recently excavated a seventh-century village with a wooden church. Closer to Maastricht, a seventh-century church and cemetery have been excavated in Inden-Pier, seven kilometres south of Jülich.

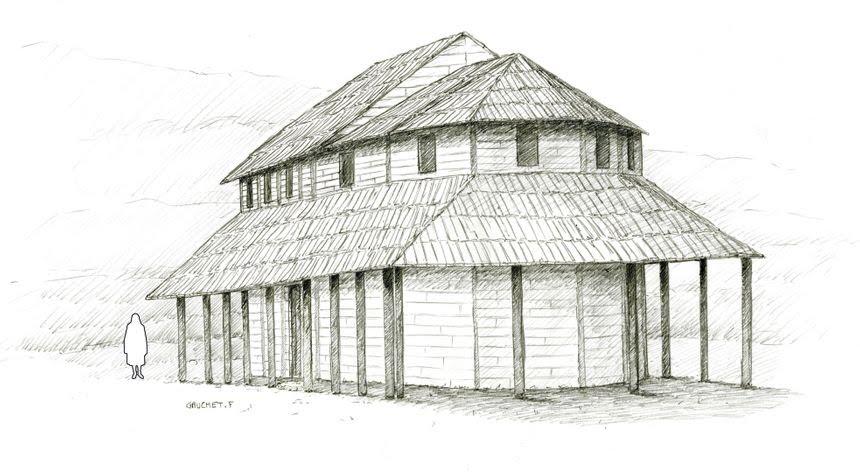

Reconstruction drawing of the wooden church at Pontarlier. Source: François Gauchet, INRAP.

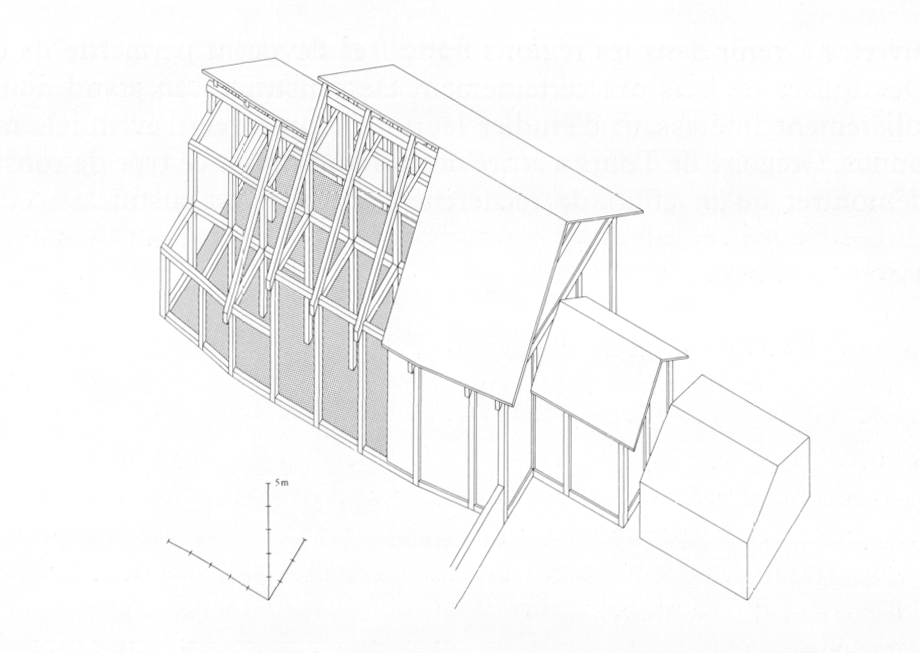

Many are simple structures following a rectangular basilica-like plan with one nave, but there are a few examples that attain a more monumental scale. For example, In Satigny, nearby Genève, a wooden church with a vestibule and a nave 13,50 metres long was built on top of the remains of a late Roman villa. Perhaps Satigny’s wooden sanctuary could compete with the splendour of its stone contemporaries.

Reconstruction of a Merovingian wooden church at Satigny. Source: Charles Bonnet, 1997: 235. Available online at Persée.

No evidence for the wooden oratory of Maastricht has come to light during excavations at St. Servatius. Archaeologists did find a rectangular stone structure or ‘cella memoriae’ of 4.3 by 3.9 meters. It is not clear whether this was Servatius’ tomb, which would contradict Gregory’s narrative. In my opinion, it is not surprising that the wooden predecessor to Monulphus’ magnum templum has not been found. Only under the right conditions are the remains of timber-frame structures preserved, but the soil of Maastricht has been heavily disturbed by later (medieval) building activity.

When archaeologists do find the remains of wooden structures, often not much more has survived the ages than the discolouration of the soil left by the rotting posts which once bore the roof. This also means that archaeologists can only speculate about what timber-framed structures actually looked like above ground. For a good deal this depends on our imagination, but we can get an idea from surviving architecture from the later middle ages. The famous stave churches from late medieval Norway are impressive with their ornate decoration of the woodwork. Similarly, the UNESCO World Heritage Wooden Churches of Southern Małopolska and elsewhere dispel the notion that wooden churches are in any way inferior to their stone counterparts.

Borgund stave church, Norway. Dating to circa 1200, it represents a different architectural style than Merovingian wooden churches, but gives an idea of how refined medieval architecture in wood could be. Source: Wikimedia.

Argument in stone

For now, there is no way to know for sure what kind of wooden structure was replaced by Monulphus’ magnum templum. But there is good reason to suspect that Gregory’s description of a flimsy chapel was exaggerated.

Much of Gregory’s writing is deeply personal, and many of his hagiographies praise family members and friends. The key person in this passage is not the dead saint Servatius, but rather the bishop Monulphus. Thus, the description of Servatius’ tomb is as much a miracle story of the saint, as it is a panegyric to Monulphus. Erecting a new church in stone would have been a considerable investment on Monulphus’ part. It would also be highly symbolical, the durability of stone securing future devotion to the saint. Thus, the metaphor of a wooden oratory snatched by the wind served to contrast the permanence of Monulphus’ stone church, highlighting his accomplishments as the shepherd of his flock.

Yet, despite its humble stature, the wooden oratory of St. Servatius may have been more permanent and ornate than Gregory’s story suggests. If so, it would have catered to a community living in and around the old Roman fort at the Meuse. Across the channel, new radiocarbon dating of a wooden church in Lincoln similarly challenges the notion that the city was deserted after the Romans departed Britain. Perhaps the wooden church of St. Servatius in Maastricht can tell a similar story of a Christian and “urban” community holding on to their way of life on the edge of the former Roman frontier.

[1] This is also the etymological background, from old Dutch Masa + Latin traiectus, combining to “ford at the Meuse”.

The reconstruction of Ansgar's wooden church at Ribe (Denmark) c. 860 might somewhat resemble the Maastricht oratorium. This mini-documentary from Ribe's VikingeCenter shows some of the aspects of constructing an early medieval wooden church.Further reading

Primary sources

Gregory of Tours, Glory of the Martyrs, translation by Raymond van Dam (1988/2004).

Gregory of Tours, Glory of the Confessors, translation by Raymond van Dam (1988/2004).

Gregory of Tours, Ten Books of Histories.

Secondary literature

Charles Bonnet, ‘Les églises en bois du haut Moyen-Age d'après les recherches archéologiques’, in: Grégoire de Tours et l’espace gaulois. Supplement à la Revue archéologique du centre de la France 13 (1997) 217-236, available online at Persée.

Bernd Päffgen and Sebastian Ristow, ‘Christentum, Kirchenbau und Sakralkunst im östlichen Frankenreich (Austrasien)’, in: Die Franken: Wegbereiter Europas. Vor 1500 Jahren: König Chlodwig und seine Erben (Mainz 1996) 407-415.

Frans Theuws, ‘Maastricht as a centre of power in the early middle ages’, in: Mayke de Jong, Frans Theuws and Carine van Rhijn ed., Topographies of Power in the Early Middle Ages (Leiden 2001) 155-216.

© Jip Barreveld and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jip Barreveld and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.