Stories of Family Separation, Child Abandonment, Incest and Reunification. From the Middle Ages to Today

This blog post explores stories of family separation, child abandonment, near-miss incest and happy family reunions in Middle English popular romances, and uncovers some of the societal and legal changes which contributed to their popularity.

"Woman Interrupts Son's Wedding After Realizing His Bride Is Her Long-Lost Daughter", "Adopted Man Marries His Mom's Biological Daughter in Wild Wedding Mix-Up", "Hours Before Wedding, Groom Finds Out That the Bride Is Actually His Sister; Know What Happened Next!". These are just a few of the sensational headlines published by news organisations ranging from China, India, and Australia to the United States of America and beyond in April 2021. They tell the story of a Chinese couple who discovered they were adoptive siblings after the bride's long-lost biological mother recognised her by a distinctive birthmark on her hand. Fortunately for the happy couple, the wedding was able to go ahead as the groom had been adopted and was not biologically related to his new bride.

This may well seem to be the kind of story that proves that truth is stranger than fiction - but it may be more apt to say that truth is as strange as fiction, since this story is oddly similar to many narratives of child abandonment, familial separation and reunification, and (quasi-) incestuous relationships from the Middle Ages.

Child Abandonment

The news stories about the Chinese couple tend to gloss over the exact circumstances which led to the bride being discovered on a roadside as an infant, merely describing the child as "lost" or "separated" from her parents. In Middle English romances, family separation occurs for a variety of reasons, often falling firmly into fairy-tale territory. In Octavian, an unfortunate mother loses her two sons to the predations of an ape and a griffin. In a confirmation of the widespread dangers posed by griffins in the world of medieval romance, one also abducts baby Degrebelle in Sir Eglamour of Artois, whereas the prideful Sir Isumbras in his eponymous romance is punished for his sins by losing not one, not two, but three sons to attacks by a lion, a leopard and, finally, a unicorn.

In what may strike us as a somewhat more realistic scenario, in Sir Degaré and Lay le Freine, newborn children are abandoned at a hermitage and an abbey, respectively, in order to forestall any suspicions of sexual impropriety which may have been aroused by the knowledge of their births. Sir Degaré's mother, who has actually been raped by a fairy knight, fears that people will assume her child is the product of father-daughter incest if her pregnancy is known, as she has been (mostly) kept away from men by her domineering father. Le Freine's mother dares not reveal that she has given birth to twins, as she had previously accused a neighbour of adultery on the grounds that a twin birth must be the result of sleeping with two men. She initially decides to kill her daughter rather than admit to slandering her neighbour or to having herself committed adultery. Fortunately, her companion persuades her to abandon the child and conceal her birth rather than resort to infanticide.

John Boswell (1988), in his pioneering study of child abandonment in pre-modern Europe indeed points to the growing numbers of illegitimate children as a motive for child abandonment. This growth in illegitimacy was facilitated by social changes over the thirteenth century such as population growth, increasing urbanisation (and thus greater opportunities for casual sexual encounters), the Church's insistence on clerical celibacy (thus rendering any clerical offspring illegitimate and socially stigmatised), and increasing formalisation of marriage rules (including, potentially, the post hoc illegitimisation of children born to incestuous unions). Other motivating factors mentioned by Boswell include the birth of children with disabilities or congenital conditions, the desire to limit breastfeeding for financial or sexual reasons (due to a prohibition on sexual intercourse while nursing a child), attempts to limit the number of potential heirs to an estate, the abandonment of children of the "wrong" gender, and the simple realities of providing for children in precarious subsistence economies. One potential explanation rejected by Boswell is that parents simply did not love their children the way "we" do: indeed, the parents who lose their children in the above-mentioned romances sorely lament their fates, while even the mothers who purposely abandon their children in Sir Degaré and Lay le Freine take care to leave them in a safe place, with certain accoutrements which serve both to indicate they come from good families - perhaps hoping, in the hierarchical society of the Middle Ages, to secure better treatment for their children - and to facilitate familial recognition and reunification in the future.

Tokens of Recognition

These items (gloves and a broken-tipped sword in Sir Degaré, a ring and a richly-embroidered cloth in Lay le Freine) are known in the critical literature as "Tokens of Recognition". The tokens often have great resonance within the plots of their respective romances. Sir Degaré avoids consummating his marriage with his own mother by remembering, at the last moment, to try the gloves on her hands, while he comes perilously close to accidentally killing his father in a fight before the fairy knight recognises his broken-tipped sword (the suggestiveness of the "female" glove and the "male" sword in this Oedipally-tinged romance has not gone unnoticed by critics).

Le Freine's token, in her romance, also serves to avert accidental incest: she has grown up to be the mistress of a rich knight, Sir Guroun, who is urged by his companions to abandon her to marry "some lord's daughter" (l. 313) - who, inevitably, turns out to be her twin sister Le Codre. This fact is thankfully discovered before the consummation of the marriage when Le Freine, in a Patient Griselda-esque sacrifice, spreads her beautifully-embroidered mantel on the marital bed. Otherwise, under a strict interpretation of incest rules, sex with one family member would create an "affinity" relationship (see below) which would prevent marriage with other members of the same family (Archibald, 2000, p. 46; Brundage, 1987, p. 194).

Incest

These episodes of "near-miss" incest are the final theme which unite these medieval romances with the contemporary viral news stories. Incest was a very popular literary motif in the Middle Ages, and the virality of this and other similar stories of incest demonstrate that it still has a certain appeal today. Incest also has a curious connection to themes of child abandonment, both in pre-modern literature and in this contemporary tale. One reason advanced by prominent religious figures in the early Church against child abandonment was the danger that one might accidentally commit incest with an unknown relative. This point was made by moralists including Minucius Felix, Tertullian, Justin Martyr and Clement of Alexandria. The latter of whom, at around the end of the second century C.E., wrote in his work The Instructor (Paedagogus): "[T]he wretches know not how many tragedies the uncertainty of intercourse produces. For fathers, unmindful of children of theirs that have been exposed, often without their knowledge, have intercourse with a son that has debauched himself, and daughters that are prostitutes".

In the modern-day Chinese tale, the "happy ending" is that the couple are still able to marry, given their lack of a blood relationship. In medieval Europe, however, they may not have been so lucky: when the marriage laws were at their strictest, in the tenth to twelfth centuries, marriage was banned between not only between people related by consanguinity (biologically) or by adoption, but also by affinity (relations formed by marriage or by extra-marital sexual relationships) and by compaternity (spiritual relationships such as godparents) (Archibald, 2001, p. 11).

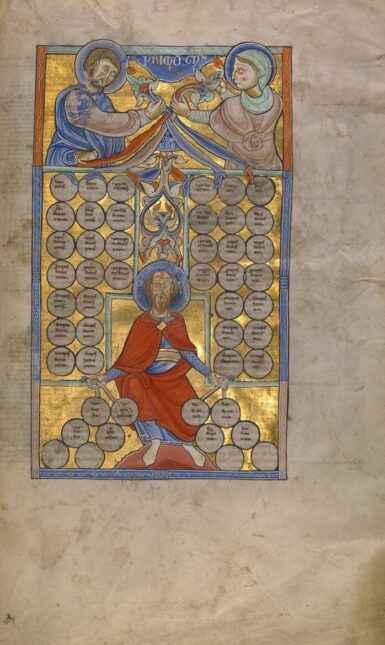

The second element which made medieval European incest laws unusually strict was changes in the way the closeness of family relationships (known as "degrees" of relationship) was calculated, and the extension of the number of degrees within which marriage was forbidden. Put simply, under the Roman system of calculating the degrees, a pair of first cousins would be related in the fourth degree, while under the German system (which was adopted by the Church from the late eighth century), the first cousins are only related in the second degree. By the twelfth century, the Church had outlawed marriages between people related by consanguinity or affinity up to the seventh degree, and by compaternity to the fourth degree according to the German system (Archibald, 2001, p. 28-29). This created such a far-reaching and potentially confusing network of relations that editions of Gratian's Decretals, the twelfth-century compilation of canon law, often included illustrative tables to help determine the degrees of relation between potential spouses. By the time of the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, the number of forbidden degrees of kinship was reduced from seven to four, in recognition that the overly-broad nature of the previous laws created serious impediments to marriage in general (Brundage, 1987, p. 356).

Conclusion

While modern laws and attitudes towards incest, marriage, child abandonment and family relationships differ in many respects to those of medieval Europe, it seems the combination of an almost unbelievable coincidence, the shocking nature of incest, the fairy-tale aspect of a recognition and the happy ending of a family separated and reunited, with a wedding to top it off, continues to pique our interest as much as ever.

Selection of relevant literature:

- Archibald, Elizabeth. Incest and the Medieval Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Archibald, Elizabeth. ‘“Lai Le Freine”: The Female Foundling and the Problem of Romance Genre’. In The Spirit of Medieval English Popular Romance, edited by Jane Gilbert and Ad Putter, 39–55. Harlow: Pearson, 2000.

- Boswell, John. The Kindness of Strangers: The Abandonment of Children in Western Europe from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance. New York: Pantheon, 1988.

- Brundage, James A. Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/he....

- Colopy, Cheryl. ‘Sir Degaré: A Fairy Tale Oedipus’. Pacific Coast Philology 17, no. 1/2 (November 1982): 31–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/131639....

- Lawton, Lesley. ‘Reconsidering the Use of Gender Stereotypes in Medieval Romance: Figures of Vulnerability and of Power’. Miranda 12 (2016): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.4000/mirand....

- Saint Clement of Alexandria. ‘The Instructor’. In Ante-Nicene Fathers of the Second Century, edited by Philip Schaff, 2:450–637. Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library, 1885. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/scha....

- Simpson, James. ‘Violence, Narrative and Proper Name: Sir Degaré, “The Tale of Sir Gareth of Orkney”, and the Folie Tristan d’Oxford’. In The Spirit of Medieval English Popular Romance, edited by Jane Gilbert and Ad Putter, 122–41. Harlow: Pearson, 2000.

© Joanna Greenland and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Joanna Greenland and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.