The cathedral of Faras: Rediscovering the submerged Nubian ‘site of remembrance’

Have you ever visited an underwater cathedral? This post takes you for a stroll on the bottom of Lake Nubia, where rest the remains of one of the most extraordinary buildings ever excavated in medieval Nubia.

Medieval Nubia: a land of (scholarly) opportunities

The ferry from Aswan, tightly packed with people, animals, and goods, sails across Lake Nubia in the chill of the desert winter morning. The passengers try to warm up with a cup of coffee or tea before they disembark at Wadi Halfa. None of them realises that a few dozen meters below them, exactly 60 years ago, one of the most important archaeological discoveries for medieval Nubia was made. On 2 February 1961, Polish archaeologists started excavating the site of Faras, ancient Pachoras, some 20 km north of the 2nd Nile Cataract. What they uncovered there were surprisingly well-preserved ruins of a large, richly decorated, and abundantly inscribed church – the cathedral of Faras.

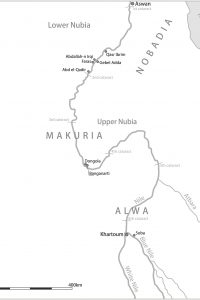

The discovery marks symbolically the birth of modern studies on the medieval Christian kingdoms of Nobadia, Makuria, and Alwa, called collectively medieval or Christian Nubia. Their history spans almost a millennium, between the 6th and 15th centuries, and abounds with fascinating events. With such landmarks as the unification of Nobadia and Makuria into one kingdom in the 7th century, the defence of Dongola, the capital of Makuria, against the Arab conquerors in 652, the journey of the Makurian prince George to the caliph al-Mutasim in Baghdad, or the conflicts between heirs to the throne in the 14th century, it could easily fill scripts of several historical books or movies. Archaeological excavations on medieval Nubian sites keep revealing examples of splendid architecture, works of arts and crafts, and inscriptions, painting a picture of a rich land inhabited by a cultivated society. Yet, medieval Nubia, located geographically and culturally in the borderland between the Mediterranean, Near East, and Africa and lingering on the margins of interests of Byzantinists, Arabists, Coptologists, Ethiopists, and Africanists, is hardly present in the public discourse. I hope this blog post will advertise medieval Nubia among the wider medievalist community as a worthwhile field of study.

Deep under water and back to the past

In 1964, the cathedral of Faras disappeared forever under the rising waters of Lake Nubia, but it is still possible to visit it. Not with a submarine, regrettably, but in the national museums of Khartoum and Warsaw, where one can admire paintings, inscriptions, and other artefacts that have been moved to safety before the flooding of the lake. However, in this time of pestilence, with travelling severely restricted and museums mostly closed, I would propose another kind of visit, perhaps even more exciting – an imaginary walk in the cathedral complex around the year 1200.

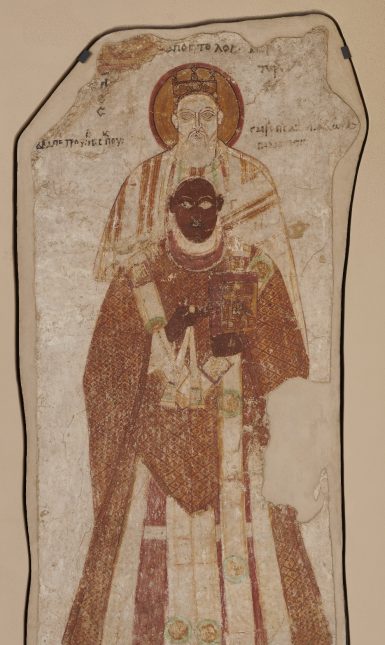

Our guide will be Ogijino, one of the medieval visitors to the church who left their signatures on the walls. Given the brevity of his memento, we may never know who he was and why he visited the cathedral. However, gathering our whole knowledge about the building from scholarly publications, photographs, and visits to the museums, and adding a bit of imagination to it, we can bring Ogijino back to life and try to see what he saw and how he could have perceived it.

A lesson in Nubian religion and history

Ogijino has come a long way from his home in Dongola, the capital city, to attend to some family business matters. When he approaches Pachoras, his sight is immediately drawn to the cathedral, towering above the city. Pious man as he is, he decides to postpone the earthly matters and first visit the holy place. The nearer he draws to the church, the greater his awe, as he apprehends its massive dimensions (25 by 23 m and 13 m in height). The central dome above the church’s naos reminds him of the unity of the Makurian kingdom and Church: a couple of decades ago, such cupolas were introduced here and in many other churches that he passed on the way on the model of the Dongolese cathedral. Ogijino climbs the hill and, upon entering the cathedral’s courtyard, he notices two impressive stone inscriptions in the corner of a nearby building. A man of letters, Ogijino reads this double text in Coptic and Greek, commemorating the foundation of the cathedral by Bishop Paulos in the year 707. They mention King Mercurius, the first Makurian ruler known to have reigned also over Nobadia, which evokes the image of the unification of two independent kingdoms and Churches, the Nobadian and the Makurian. Intrigued by these remarkable historical inscriptions, he cannot wait to see the church and he rushes inside.

He first walks to the front, where a huge painting of the Nativity catches his eye. On the opposite side of the apse, he notices the scenes of the Passion cycle. As his eyes skim the walls, he recognises further images, biblical scenes and figures of saints, that he can ascribe to particular feasts in the liturgical year. And he suddenly realises that this is in fact an illustrated liturgical calendar: the murals are arranged in a chronological sequence, starting with the Nativity in the north-eastern corner and ending with the autumn celebrations in the northern aisle.Thus, even those who could not read could follow the rhythm of the celebrations (Zielińska 2010).

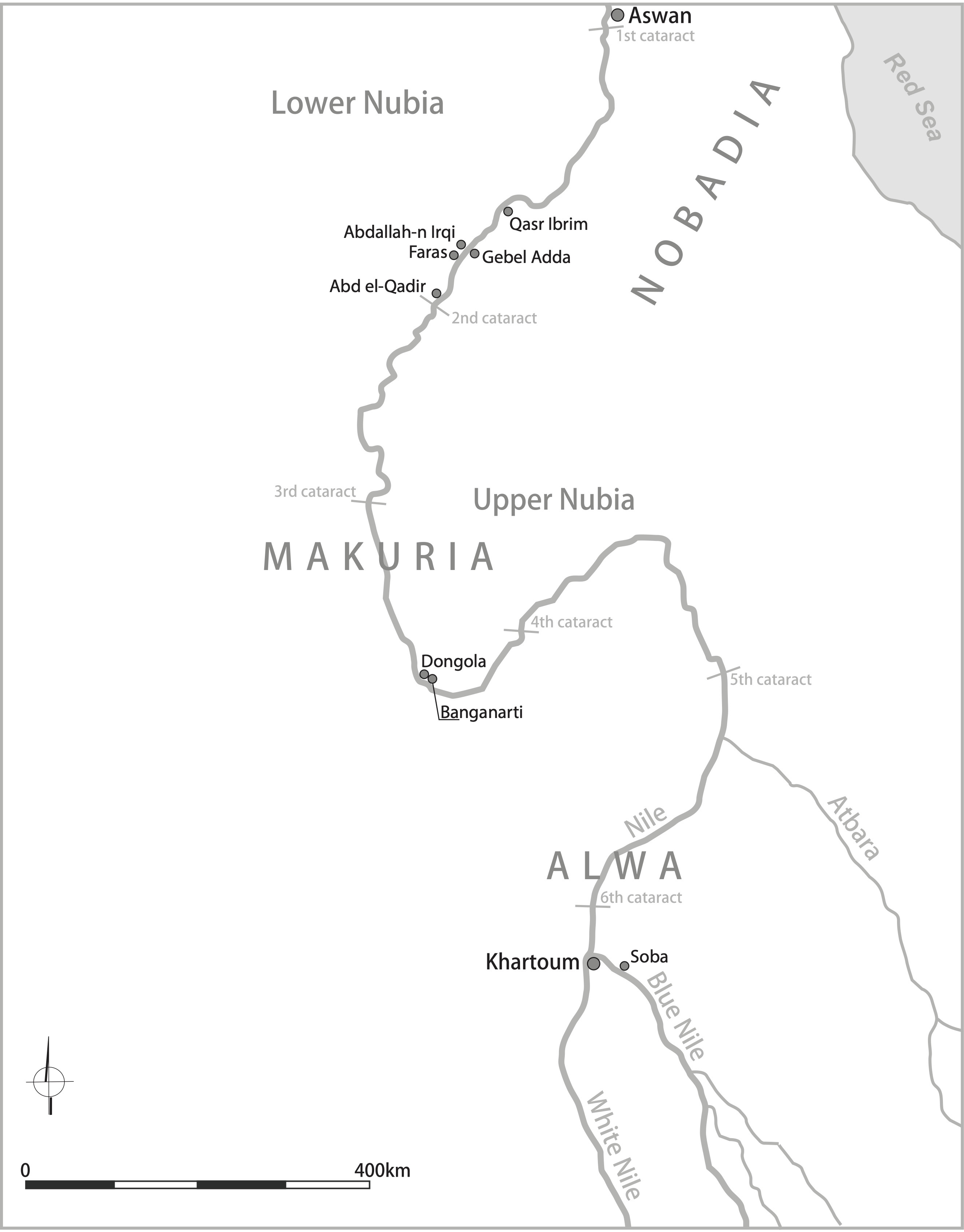

Right next to the Nativity scene, Ogijino sees an image of a familiar-looking figure. He reads the accompanying inscription: “This is the sweet king, Moses George”. And indeed, this is the current king of Makuria (1155–c. 1190s), but still very young – the painting must have been executed shortly after his coronation. Now Ogijino starts noticing the portraits of other kings as well as queen mothers and bishops of Faras intertwined with religious images. The cathedral’s walls have been turned into a true royal and episcopal gallery. In the capital, Ogijino has already had occasion to see the king, but for the locals, these paintings were surely the closest they could ever get to seeing the royal family in their lavish attire. No doubt there were persons around who could explain who was who and relate the kingdom and bishopric’s histories.

While Ogijino is praying for the king’s health and salvation, he notices that people are flocking to a room in the south-eastern part of the cathedral. Intrigued, he follows the others and finds himself in a chapel. A priest comes in and proceeds to an altar beneath the representation of Christ Emmanuel flanked by two archangels. He stops in front of an inscription written to the right of Christ’s figure. Ogijino comes closer and sees that the text is a table with the names of all past bishops of Pachoras, the length of their episcopate, and the day of their demise. The priest reads from the text that today, on Epiphi 26 (= 20 July), is the anniversary of Bishop Petros’ death (d. 999) and starts the commemorative liturgy. After the initial prayers at the altar, the priest walks to the portrait of the bishop on the room’s western wall and continues the celebrations. He then leads the faithful in a procession to Petros’ tomb outside the cathedral. There, he recites the bishop’s epitaph inscribed in the funerary chapel and concludes the service.

On his way back, Ogijino visits other tombs in the bishops’ necropolis surrounding the cathedral. He reads the Greek and Coptic epitaphs accompanying the burials and, while praying for the deceased hierarchs, he learns some details about their lives, how long they lived or what they did before being ordered bishops.

Worshipping God, remembering the living

At the entrance to the cathedral, Ogijino passes a group of youngsters sitting on the sand in front of a deacon. The deacon dips his kalamos in an inkpot and writes the letters of the Coptic alphabet on the wall of the church. The pupils copy the alphabet, more or less skilfully, on pieces of broken pottery. Ogijino rejoices at how the Church takes care of education, so that the young generations may perpetuate the memory of the Makurian kingdom and Church and he suddenly feels the urge to become a part of this memory, too. He re-enters the cathedral with the intention of signing his name on the wall. Before he finds an appropriate spot in the northern vestibule, he reads aloud the prayers left by his predecessors. Some of the visitors’ names sound familiar– could they have come from Dongola, too? – others are definitely local; some of the inscriptions are beautifully executed, others belong to less skilful writers; some are long prayers, others contain but the pilgrim’s name. Yet, all these intercessions are equally valid in the eyes of the Lord, who can constantly hear them. God is of course their main addressee, but the living also play an important part: by reciting the prayers, they perpetuate their predecessors’ memory and integrate it with the Nubian memory. Having all this in mind, Ogijino writes: ‘I, Ogijino, O Jesus!’ (published in Kubińska 1974, no. 52), and then leaves to tend to his business.

Together with Ogijino, we have travelled deep under water and far back in time to have a lesson in Nubian memory. We have discovered how different elements of the Faras cathedral worked together to create an intricate memorial design serving both God and the mortals, a true ‘site of remembrance’ (lieu de mémoire), as Pierre Nora would put it.

Further reading:

S. Jakobielski, A History of the Bishopric of Pachoras on the Basis of Coptic Inscriptions, Warsaw 1972

S. Jakobielski et alii, Pachoras/Faras: The Wall Paintings from the Cathedrals of Aetios, Paulos and Petros, Warsaw 2017

J. Kubińska, Inscriptions grecques chrétiennes, Warsaw 197

D. A. Welsby, The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia. Pagans, Christians and Muslims along the Middle Nile, London 2002

D. Zielińska, ‘The iconographical program in Nubian churches: Progress report based on a new reconstruction project’, [in:] W. Godlewski & A. Łajtar (eds), Between the Cataracts. Proceedings of the 11th Conference for Nubian Studies, Warsaw University, 27 August–2 September 2006, II: Session Papers, Warsaw 2010, pp. 643–651

This blog post was written within the framework of the IaM NUBIAN project, funded from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 842112.

© Grzegorz Ochała and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Grzegorz Ochała and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.