The Discovery of the Middle Ages in Korea

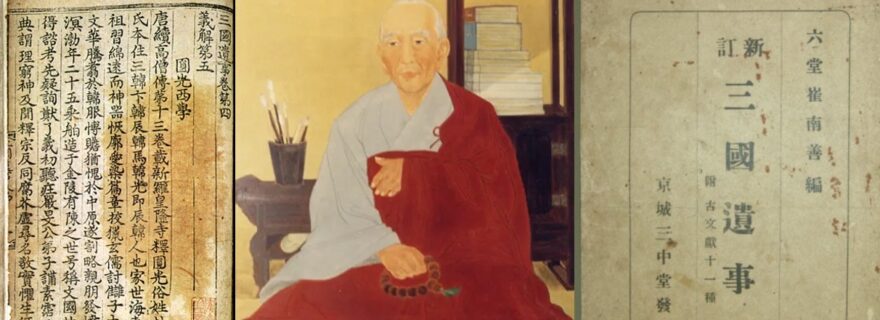

The Vestiges of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea (Samguk yusa) is the most famous medieval text from the Korean peninsula, occupying a central position in research into the period and in the maintenance of Korean identities. Its coming-into-being as a seminal text however is not straightforward.

A dearth of sources

It is a familiar feeling for anyone working on Antiquity and the Middle Ages on the Korean Peninsula: the short surge of excitement when one encounters a source not read before, immediately followed by the realisation that it is only the title of the source that is extant. The source itself is long gone. One of the mysteries of the study of the Middle Ages on the Korean Peninsula is its absolute and relative paucity of sources. If for convenience sake we treat the Koryŏ 高麗 state (918-1392) roughly as coterminous with the medieval period,[1] then we are discussing a period that lasted five centuries. Korea’s antiquity lasted longer and has left us with even fewer written sources, but antiquity was in no way comparable to the medieval age in terms of the keeping of records, the production of texts (official, private, religious, commercial), or the centrality and prestige of reading and writing. Yet, the total volume of extant textual sources (overwhelmingly in Classical Chinese) from the Koryŏ period [2] is such that it comfortably fits into one of the bookcases in my office - with some room to spare. A recent work of secondary scholarship I purchased underlines this state of affairs: it is a compendium of all the books we know to have existed in the Koryŏ period, but which have not survived except for their titles. This book shows considerable overlap with a document on my computer that is usually open: in it, I note down all titles of no longer extant Koryŏ period works I encounter.

The Vestiges of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea (Samguk yusa 三國遺事)

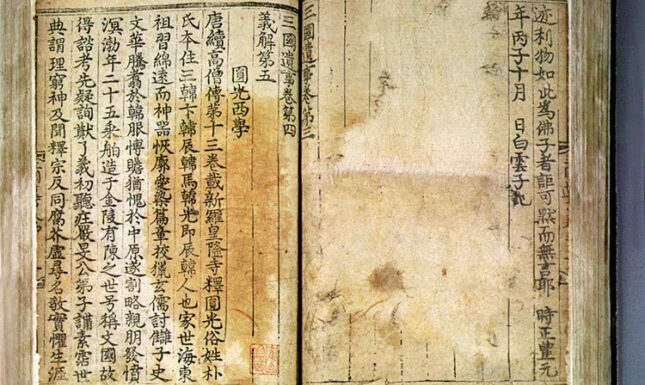

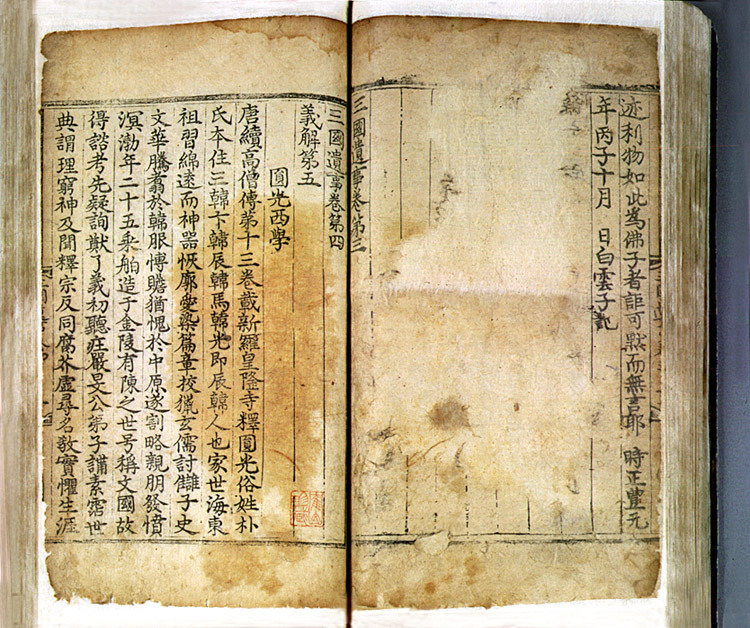

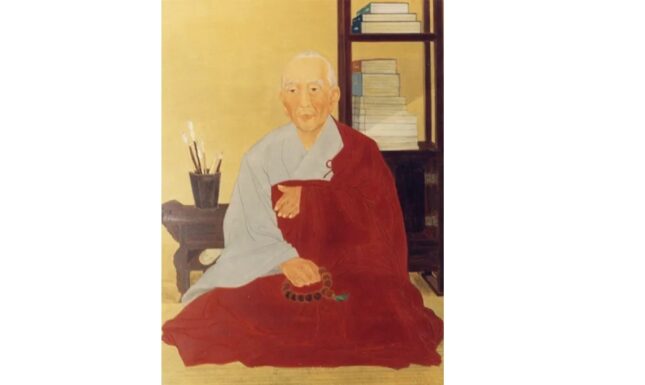

Among the texts that do survive, the Vestiges of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea (Samguk yusa 三國遺事) occupies a place of some importance. Presented to the Koryŏ king (who by then was more of a Mongol than a Koryŏan) in 1281, it is only the second history of the peninsula from the Koryŏ period to survive (the first being the Records of the Three Kingdoms - Samguk sagi 三國史記- presented to the king in 1146). It contains the first record of (and indeed starts with)[3] the founding myth of the Koreans as a people, the myth of Tan’gun. It was compiled by Buddhist monk and scholar Iryŏn 一然 (1206-1289),[4] completed by his disciple Mugŭk 無極 (1251-1322), and published by an unknown third person in 1360. It is a compilation of historical facts, origin myths, strange and bizarre stories, legends, folktales, genealogies, and remnants of older records that are no longer extant. It is great fun to read and a pain to translate.Modern scholarship agrees that the reasons for compiling Vestiges consisted of (a) an effort to strengthen royal authority by firmly associating the history of the peninsula with its rulers, who had become virtual strangers to their own land and people due to the forced intermarriages with the Mongol Imperial House, and (b) an effort to provide Buddhist views on the history of the peninsula. Despite its auspicious beginnings in the form of a royal command by King Ch'ungnyŏl 忠烈 (r. 1274-1308) that led to its composition, the Vestiges was only printed in 1360, right before the demise of the Koryŏ dynasty and towards the end of the Middle Ages on the peninsula. During the following Chosŏn 朝鮮 period, the ideological landscape changed to such a degree that the text was all but forgotten. From time to time, scholars with an antiquarian interest in Korean history would cite it distastefully, but the text was not studied or taken seriously.

Later criticisms

An Chŏngbok 安鼎福 (1712-1791), arguably Chosŏn’s leading historian in the 18th century, made quick work of Vestiges:

"Written in the mid-Koryŏ period by the monks Mugŭk and Iryŏn, the work altogether consists of five fascicles. Since this work was originally composed to transmit Buddhist sources, while historical periods can be roughly examined through the work, it is otherwise a collection of heretical and fallacious narratives. In the time of our dynasty, it has been used as a reference source in the writing of the Tongguk t’onggam, and the place names that appear in the Yŏji sŭngnam have also been based on it. Alas! This is a heterodox collection of anomalies and yet it has managed to survive and be transmitted over time." (An Chŏngbok, TSKM pŏmnye: 12a-b)

A famous geographical encyclopaedia noted the same about Vestiges: usable on the purely factual level of place names, but in any other aspect untrustworthy, for the book was "factually dubious and cannot be trusted entirely," even though "it bears clear evidence with respect to the entries of the Three Han (Samhan 三韓)," for which readers should nonetheless "duly consult it" (Chŭngbo Tongguk yŏji sŭngnam 增補東國與地勝覽).

Mistakes, inconcistencies, and the progenitor of the Korean people

To be sure, in the eyes of Chosŏn Neo-Confucian scholars, exemplars in rigid textual criticism, it was clear that Vestiges was tainted because it had been written in a Buddhist environment and under Mongol domination. Even worse, perhaps, was the shoddy editing that characterised the book. Tan’gun 檀君, the Korean people’s mythical progenitor whose myth was for the first time recorded in Vestiges appears in the very first entry after the foreword. But he does so in what is the second fascicle. There is a first fascicle that precedes even the foreword and contains tens of pages of chronologies of rulers and states. Tan'gun, interestingly enough, does not figure in this Dynastic Chronology of Rulers, even if other mythical rulers do. What is more, despite the title of the book (Vestiges of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea), the Dynastic Chronology of Rulers features four kingdoms of which it gives the rulers, not three. Then there are legion editorial and other mistakes in the text itself - interlinear commentaries that contradict one another, textual incongruities, the last sentence of an entry ending up as the title of the next entry and so on and so forth.

The Vestiges of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea was in other words a most improbable book to became emblematic of the Korean Middle Ages (and Antiquity), yet that is precisely what happened. The book is often seen as the beginning of a Korean national consciousness, when anti-Mongol sentiments coalesced in a region-transcending entity. Moreover (and despite its title), the inclusion of Tan'gun had made peninsular history older by two millennia and had demoted the founders of the Three Kingdoms to the status of (much) later and less relevant followers. The Three Kingdoms (of which there were four) may have been divided, but Koreans were originally one united people. In other words, Vestiges was brimming with future potential.

A timely reprint

Before we get to the moment when Vestiges would become the emblematic text that characterized both antiquity and the Middle Ages on the Korean peninsula, there is one other moment that bears paying attention to. In 1512, Vestiges was reprinted – it is that edition that in all probability is now the oldest extant printed version. By then, Vestiges was widely criticized for its unconventional form and content. It was by no means a popular text – in Neo-Confucian terms, the text was not only heterodox, but could be considered heretic. Still, a learned group of Chosŏn Neo-Confucian scholars and civil officials came together to finance a reprint – the old woodblocks were no longer usable though:[5]

"The Samguk sagi and the Samguk yusa (Vestiges) that were written in the Three Kingdoms that make up our Eastern Country have never been printed except in our offices here in Kyŏngju. But that was long ago and characters on the printing blocks have worn out or gone missing, so that now one can barely read four or five characters of each line."[6]

Both Vestiges and Histories of the Three Kingdoms were no examples of proper scholarship, but there was nothing else that remained of the Middle Ages and as such, value must be found in these works by previous generations of scholars, who may have been misguided, but had also been erudite. As the group of Chosŏn Neo-Confucian scholars and civil officials led by Yi Keybok wrote in the afterword of their 1512 edition:

"Carefully considering this, I come to the conclusion that since scholars were born on this earth, they have looked at the histories from different countries under Heaven from all possible points of view, wanting to broaden their knowledge on order and chaos in societies and the rise and fall of states and on all kinds of miraculous vestiges of the past. While living in this country, how could they ignore its affairs and history?

[…]

That is why I wanted to publish a revised edition of the Samguk yusa. I have searched far and wide for a complete copy, but in my perusal of many records, I was not successful in obtaining it. The text has from early on always found very limited distribution in society. As a result people could not easily lay their hands on it to read and know it. If I do not publish a revised edition now, I fear that its transmission will be broken. Then this would lead to the past affairs of our Eastern Country not being known to later scholarship, and that would be surely regrettable. Fortunately, our esteemed and learned magistrate of Sŏngju, Lord Kwŏn Chu, had heard of my quest and obtained a complete copy, which he sent to me. I gladly received the book."

It took the intervention of a very high-ranking official, but a complete copy was found, new woodblocks were carved,[7] and a new edition, destined for the same neglect and condescension the older versions had received, was duly published.

A triumphant return

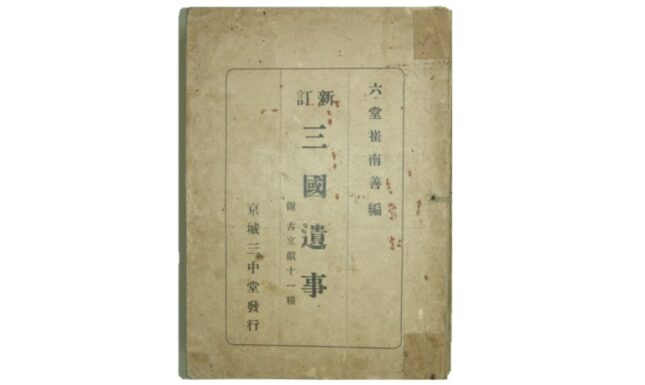

Given the low reputation Vestiges enjoyed during the long Chosŏn period (1392-1910), the 1512 edition was an unexpected boon. After Japan annexed Korea in 1910, previously impopular and neglected texts and tradition drew the interest of Korean intellectuals trying to make sense of the colonial predicament and to retain, recover, and reconstruct as much of Korean independence (in all respects) as they could. As a result, Ch’oe Namsŏn 崔南善 (1890-1957), perhaps the towering figure in cultural and intellectual colonial Korea, published "A bibliographical essay on the Samguk yusa" (Samguk yusa haeje) in 1927. Drawing upon his unparalleled collection of ancient, medieval, and old manuscripts and texts, and his extensive knowledge of the historical periods involved, and their languages, Ch’oe re-evaluated Vestiges, the first person to give it its position as the medieval age’s most seminal text. Many would follow. Ch’oe "with a broad and critical eye, collected information that was left out or neglected from early histories and brought to light hidden and obscure matters."[8] His appraisal turned the traditional appraisal of Vestiges on its head: “there is no reason to think the content is incredible or to dismiss them because they appear odd and (stylistically) poor," or because they have been long considered as "fleeting matters and fragmented stories heard and gathered at convenience." Vestiges was valuable precisely because it includes these items that add to the wide-ranging variety of episodes and convey the spontaneous nature of life ("whatever reached the eyes, ears, and hands without prior notice"), which could not be found in other sources.

Ch’oe’s edition of Vestiges was a huge success in colonial Korea. It gave historical credence of a kind to the myth of Tan’gun (and as such played a major role in the establishment of Korean religions centered around Tan’gun – some of which are still around today), and it enabled Ch’oe Namsŏn to construct an enormously influential historical counternarrative to Japanese colonialist narratives that robbed Korea of its independence and historicity. Ch’oe’s understanding of Korean antiquity and subsequent history through the Middle Ages to today is still important – all through the medium of one medieval text. The text had already been introduced once during a time of national crisis (the Mongol domination of Koryŏ) - but it hadn't stuck then. But now that it was introduced again, as it were, in a period of national crisis, it would. More than any other premodern text, Vestiges came to be the focal point of Korean national identity. The fact that even now each year one or two new translations of Vestiges into modern Korean (the text was written in Classical Chinese with some Old Korean thrown in for good measure) appear says much about its enduring importance for the present generation.

Ch’oe Namsŏn’s edition is still the standard edition used today. It would have been of great significance if we would have known precisely what texts and manuscripts Ch’oe worked with while he was editing Vestiges into the shape it was to hold for the next century (and perhaps longer). How much did he rediscover, how much reconfigure? But his incredible library (which reportedly held up to 150,000 manuscripts, documents, and books) was destroyed during the Korean War. It is possible that new discoveries await us: older versions of Vestiges that will tell us whether the Dynastic Chronology of Rulers was an original part of the text. Whether the foreword was supposed to be placed after the first fascicle instead of before it. Whether the editorial mistakes are original or the fault of later interpolations.

Be that as it may, for now it is clear that Vestiges is not so much a book, as a collection of very diverse texts (and not exactly run of the mill texts at that), that its structure is problematic, that it is full of editing errors, and that in the absence of conclusive evidence how and when the text was originally compiled, it is an open text that may yet change if different (parts of) versions of the manuscript are found. Vestiges is not the monolithic text it is often made out to be (whether it is called typically Buddhist, Korean/Koryŏan, folksy, spiritually based, or (proto-)nationalist).

There is no contemporary text quite like Vestiges in Korean history, which has given it a position of importance. It is the text that holds the first recording of Korea’s origin myth (and a precise date for its founding: 2333 BCE, October 3 – what’s in a date?), it is a text that holds a treasure trove of historical and other details not found in other sources. As such, it played and plays an important role in understanding the Korean Middle Ages. There is a real gap between the academic appreciation of Vestiges as a text and its role in the formation and maintenance of recent and contemporary Korean identities. Academic understanding of that role is of course one way to deal with this issue (and perhaps a very 'Leiden' way to do so), but this could lead to further solidification of Vestiges as an unassailable and monolithic text, which underestimates or even denies it fundamental diversity, ambiguity, and tendency to include rather than exclude even the stuff that drives the average historian crazy.

Had it not been for the remarkable intervention by Ch'oe Namsŏn during the colonial period, Vestiges as a text would not have lived the way it does now, nor would it have occupied such a formidable position in Korean identity discourses, or in the study of Korean Antiquity and Middle Ages. We need to remember though it is a collation of different texts: collated at two moments (1270-1290s and ca. 1360) and reconstructed in 1927. The reconstruction is an on-going process.

Notes

[1] For which there are actually very good reasons, as good as they are contingent.

[2] I do not include Chinese, Manchurian, and Japanese sources here.

[3] Or does it? The standard edition of the text now starts with the Dynastic Chronology of Rulers, but there are good reasons to suppose that this chronology is a later addition.

[4] Iryŏn was so famous, his place of birth profited from the connection: “Changsan-gun, originally Amnyangso-guk {also called Ap-tok}: In the Shilla period King Chimi took it and made it a kun. King Kyŏngdŏk renamed it Changsan-gun with a different character for chang. During the early Koryŏ period, its name was changed to its present name. In the ninth year of Hyŏnjong 1018 it was made subordinate to Kyŏngju. In the second year of Myŏngjong (1172), a kammu was established there. When King Ch’ungsŏn ascended the throne, it was renamed Kyŏngsan, so as to avoid the personal taboo name of the king. In the fourth year of King Ch’ungsuk (1317), the administrative status of Changsan-gun was raised to that of a magistracy because it was the hometown of kuksa Iryŏn. (KS 57: 3b).” According to his stele inscription, he was serious and never made jokes. He was aloof, because ‘when he was among a crowd, it was as if he was solitary.’ Yet he was seen to be humble: ‘When he had been appointed as kukchon (National Honored One), he behaved as if it was a humble position.’ He was well-read in the existing abundance of Buddhist texts, but as much in the works of the classical Sinitic philosophers, Confucian thinkers, and the commentators on these traditions.

[5] This is the group, in order in which they signed the afterword to the new print edition: Yi Kyebok, puyun (Magistrate), ch’usŏngjŏngnan kongshin (Sincere Calamity Pacification Meritorious Subject), kasŏn taebu (Kasŏn Grand Master), kyŏngju-jin pyŏngma chŏlchesa (Kyŏngju Fortress Military Commander), and chŏnp’yŏng-gun (Lord of Chŏnp’yŏng); Yi Sanbo, saengwŏn (Classics Licentiate); Ch’oe Kidong, kyojŏng saengwŏn (Proof-reading Classics Licentiate); Yi Yu, chunghun taebu (Chunghun Grand Master), haeng Kyŏngju-bu p’an’gwan (Acting Magistrate’s Aide for Kyŏngju), Kyŏngju-jin pyŏngma chŏlchedowi (Kyŏngju Fortress Military Deputy Commander); Pak Chŏn, pongjingnang su Kyŏngsang-dosa (Gentleman for Forthright Service and Acting Inspector of Kyŏngsang-to Province); An Tang, ch’usŏngjŏngnan’gongshin (Sincere Calamity Pacification Meritorious Subject), kach’ŏng taebu (Kach’ŏng Grand Master), and kyŏngsang-do kwanch’alsa kyŏm pyŏngma sugun chŏlchesa (Provincial Governor of Kyŏngsang Province and concurrently Army and Navy Commander).

[6] See the “Afterword” in Iryŏn, Remco E. Breuker, Grace Koh, Frits Vos and Boudewijn Walraven. Vestiges of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea: A Translation of the Samguk Yusa. Library of Korean Classics. Honolulu: Hawaii University Press, Forthcoming.

[7] Which was more economical than using movable type. Movable type needed serious investment, even if the technology itself is a medieval Korean technology, predating Gutenberg by two and perhaps as much as three centuries.

[8] I have taken all quotations from Ch’oe’s essay out of our critical introduction to the translation of the Samguk yusa: Iryŏn, Vestiges of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea: A Translation of the Samguk Yusa.

© Remco Breuker and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2024. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Remco Breuker and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.