The Latin Aegean: crusade, colonialism, and commercialisation

Small, victimised, and on the fringe, though not over and done. How crusading shaped Late Byzantine socioeconomic life and how the Aegean world defied Latin dominance in times of conquest and exploitation. A story told from history and archaeology.

Introduction: big events in a small world

The Latin or Frankish [1] Aegean (ca. 1200-1500) is a small but intriguing part of Mediterranean history as its story covers a prominent transitional phase. Throughout (pre)history, the Aegean was an intersectional point of Afroeurasian connectivity and the heartland of Byzantium. Aegean communities were often subjected to international turmoil and certainly did not escape the encroachment of Latin Christendom. During the early 13th century, Western powers shattered Byzantine hegemony. In 1204, members of the Fourth Crusade captured Constantinople and established the short-lived Latin Empire (1204-1261). Consequently, many Byzantine territories were colonised. This led to regional destabilisation and fragmentation and, simultaneously, opened up the Aegean economy to the West (Jacoby 2017). These processes changed Aegean society. The region existed at the fringe of an expanding Europe, forming a frontier of Latin conquest. In it, crusaders were fighting ethnoreligious opponents, namely Turks and Orthodox Greeks. Latin oppression and exploitation of native communities were, however, less successful than elsewhere.

Of course, this story is firmly located within written history. Below, however, I want to persuade the reader of the added value of archaeology and in particular the promising potentials of ceramic research. Such studies contribute to a fuller reading of the crusader past, either affirming, nuancing, or perhaps even contradicting prevalent assumptions in historical discourse.

Economic opportunities and geopolitical realities

The Latin Aegean defined as ‘frontier zone’ makes sense. However, views on what a frontier is, are changing. One innovation is to perceive it less militaristically and emphasise economic and social dimensions. Frontiers form segregating borderlands but are also areas of intense cultural and commercial contact. Studying supra-frontier trade is a fruitful way of approaching this. In Latin expansionism, trade and crusade were deeply entangled - a relationship both symbiotic and mutually damaging. Merchant-crusader interdependence is seen in the case of the Frankish Aegean. Western traders and knights had differing motives to be involved in crusading. They facilitated each other’s needs but could also hinder one another. Merchants, mostly from Italian city-states, needed the military strength of Latin armies to gain access and control over foreign markets but were wary of the disturbance caused by warfare. Crusaders, in turn, needed Italian ships and finance to consolidate their rule, but this reliance made them highly dependent on these untrustworthy merchants too. Another major player was the clergy, although Catholicism never got a foothold in Byzantine society. The Church, whilst crucial in legitimising crusade, also obstructed more worldly Latin objectives. Papal bulls prohibiting Christian-Muslim commerce, for instance, created problems (Carr 2015). These bans limited the options of Franks to sell their colonial surpluses at Islamic consumer markets (principally those of Mamluk Egypt and the Anatolian beyliks). Missed revenue resulting from such boycotts, meant less funding for actions against 'enemies of the Faith'. The inability to freely trade endangered the livelihood of Latin territories too. Their settlements, far from being self-sufficient, relied heavily on shipping as a lifeline for much-needed supplies. Limiting accessibility to overseas markets thus added risk to an already precarious situation. Subsequently, this form of economic warfare proved counterproductive and was at times rejected. The Latin frontier was here, in reality, less impregnatable than popes demanded, but, at the same time, not as porous as traders and warlords hoped. As shown below, exchange (involving pottery) did not necessarily follow the geopolitical boundaries of this east-Mediterranean borderland.

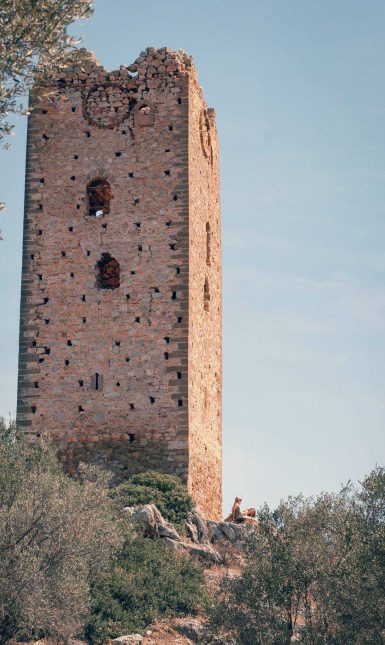

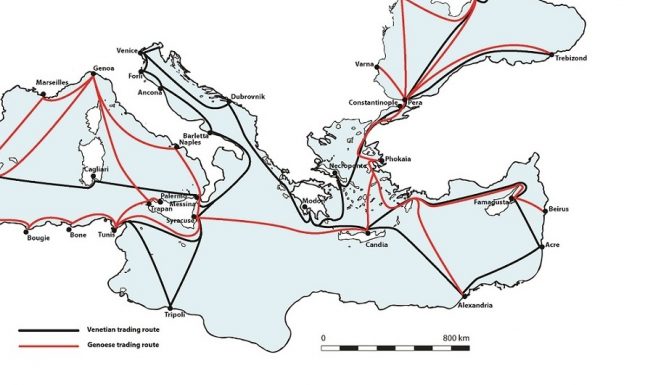

Efforts of creating durable and industrious colonies in the East not always brought fruition. Conquering land was one thing, establishing viable settlements and maintaining productive estates proved something else. This was not the least because of insufficient European migration to populate conquered territories. Additionally, the harsh and unfamiliar environment made the region inhospitable to Westerners, both socially and ecologically. Moreover, Franks occupying Aegean lands did not form a unified front. Violent territorial disputes between different crusader factions erupted occasionally, adding to an already confused situation. Frankish presence left a minor footprint as the Aegean remained, at most, half-conquered, although Frankish towers (fig. 1), still dotting Greek landscapes today, are impressive reminders of Latin heritage. Crusading did nevertheless impact the region economically. With Latin conquest came colonial exploitation and the introduction of Western-style regimes like feudalism, while agricultural and industrial outputs became increasingly market-oriented. This was accompanied by an upscaling and redirection of trade, geared more towards Europe, with Constantinople losing attraction. Investments were made in defensive structures and harbour facilities of cities aimed at promoting mobility and commerce by sea. Venice and Genoa, having significant economic interests in the Aegean, were prime initiators (fig. 2).

Travel and trade, ships and sherds

Back to archaeology: why study pots instead of texts in investigating crusader history? Pottery was pivotal in premodern economies and can serve as a proxy for a wide range of socioeconomic developments otherwise untraceable in medieval archives. Much of Aegean commerce remains unclear, with surviving sources being partially illuminating at best (Lock 1995). Salient questions surrounding who produced and consumed what, what was traded, in what quantities, by what routes and what means, are hitherto shrouded in uncertainty. Changes in organisation, scale, direction, and intensity of maritime exchange can be studied by researching potsherds. Here, the emphasis lies in the potential of spatial pottery distributions to ‘map’ economic connectivity within and beyond the waters of this Mediterranean frontier zone. Medieval Aegean pottery was transported far from its production centres, as containers carrying other goods or as sellable items themselves. Distribution patterns seem typified by a strong sea-oriented diffusion, with high concentrations at coastal sites and sparser finds inland. This is hardly surprising since the main mode of transport was seaborne. It needs to be said, however, that the significance of land transportation is an underexplored topic. Regional roads and provincial fairs could have played an important yet unclear (re)distributive function. Localised trade in agrarian surpluses, often prepared, stored, and consumed in pottery, was a considerable part of the Byzantine economy. However, the current state of research makes it hard to assess the movement of ceramics through the Greek countryside.

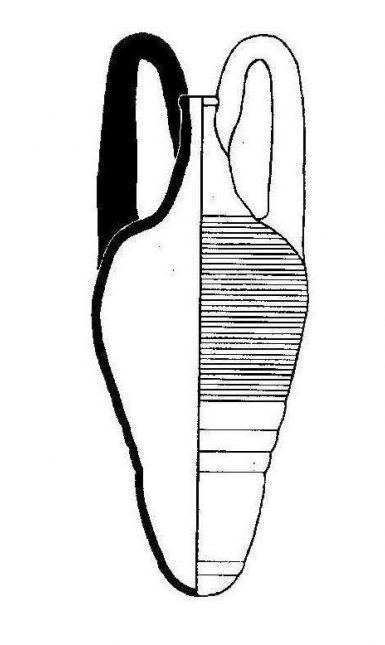

Pottery, especially fine wares and amphorae (containing oil, wine, and grain), was familiar cargo across Mediterranean seas. Following crusader conquest, bulk export of Greek produce to the West increased, answering growing consumer demand. Discoveries of Aegean shipwrecks confirm the large-scale transportation of amphorae (e.g. at Yenikapı and the Merara Islet). Table and kitchen wares on board, on the other hand, were often smaller in number, being personal belongings of crewmembers. Dishes and cooking pots could be purchased and sold during petty trade at coastal marketplaces en route. Such small-scale irregular commerce was a popular way for seafarers to circumvent official state-controlled markets, thereby avoiding taxation. Additionally, mass-transportation of glazed wares did occur, as huge quantities of such pottery at shipwreck sites indicate (e.g. at Kastellorizo Island and Novy Svet). Piracy and naval war were omnipresent phenomena frustrating maritime trade. Corsairs and privateers could take possession of a ship’s cargo and make a profit by selling confiscated goods. Such unregulated or criminal practises of ‘exchange’, complicate our reconstruction and understanding of Aegean trade. Their redistributive power was likely considerable, causing deviations from conventional producer-consumer relations. Aegean geography enabled such complex configurations - its numerous peninsulas, bays and scattered islands were well-suited for cabotage, benefiting merchants and outlaws alike. Coastal tramping and island hugging were important strategies in regional communication. Treacherous winds and currents made direct open-sea journeys less popular, as attested by the discovery of many shipwrecks (e.g. at the islands of Skopelos and Kavalliani). The Aegean seascape allowed for a dense network of interlinked waterfront locations between a ship’s point of departure and final destination, generating an interactive system. These short- to medium-distance seaways were more familiar to native sailors than their Latin counterparts. This ensured Greeks a vital position in regional traffic under crusader rule.

Fig. 4. Fragment of Zeuxippus Imitation Ware. Unknown find spot, ca. 13th-14th cent. AD (photo: the Chicago Museum).Fig. 5. Fragment of Polychrome Sgraffito Ware. Unknown find spot, ca. 13th-15th cent. AD (photo: the Chicago Museum).Fig. 6. Zeuxippus Ware dish. Unknown find spot, ca. 13th-14th cent. AD (photo: Vroom 2014, 108).Fig. 7. Fragments of Roulette/Veneto Ware. Unknown find spot, ca. 13th-14th cent. AD (photo: Vroom 2014, 132).Fig. 8. Fragment of Fine Sgraffito Ware. Unknown find spot, ca. 12th-13th cent. AD (photo: the Chicago Museum).Fig. 9. Fragment of Proto-Maiolica. Unknown find spot, ca. 13th-14th cent. AD (photo: Vroom 2014, 126).

Conclusion: crisis and resilience

The abovementioned survey of pottery research allows two preliminary observations. First, the wide-ranging diffusion of Aegean ceramics shows the region’s capabilities of significant economic output and interaction in a time ofpresumed chaos and triviality. The archaeological record shows the continuation of productivity and the acceleration of trade in this supposed colonial backwater. However, these developments should not simply be framed in a bilateral relation between a European core and an east-Mediterranean periphery. This because secondly, Latin-directed interregional trade was only one part of an elaborate exchange network, of which many goods circulated in and around the Aegean, rather than being straightforwardly shipped to and from Europe. The Latin Aegean should, therefore, not be characterised as merely an exploitable hub or transit zone. This Eurocentric view disregards the dynamic and peculiar nature of the region’s commercial life and its interconnectivity, much of which awaits unearthing both literally and figuratively.

[1] Here, the terms ‘Franks’ and ‘Frankish' are used to denote all west-Europeans in Greek lands associated with the crusades, based on the Byzantine usage of the word 'Phrankoi'. In many related studies ‘Frank’, ‘Crusader’, and ‘Latin’ are used interchangeably.

Further reading

Boas, A.J., 1999. Crusader Archaeology. The Material Culture of the Latin East. London and New York: Routledge.

Carr, M., 2015. Merchant Crusaders in the Aegean, 1291–1352. Woodbridge: Boydell.

Chrissis, N.G. and M. Carr (eds), 2016. Contact and Conflict in Frankish Greece and the Aegean, 1204–1453. Crusade, Religion and Trade between Latins, Greeks and Turks. London and New York: Routledge.

Davies, S. and J.L. Davis (eds), 2007. Between Venice and Istanbul: Colonial Landscapes in Early Modern Greece. Athens: ASCSA.

Jacoby, D., 2017. Western commercial and colonial expansion in the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea in the Late Middle Ages, in: G. Ortalli and A. Sopracassa (eds), Rapporti mediterranei, pratiche documentarie, presenze veneziane: le reti economiche e culturali (XIV-XVI secolo), Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 3-49.

Lock, P. 1995. The Franks in the Aegean, 1204-1500. London and New York: Longman.

Tsougarakis, N.I. and P. Lock (eds), 2014. A Companion to Latin Greece. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Vroom, J.A.C., 2011. The Morea and its links with southern Italy after AD 1204: ceramics and identity. Archeologia Medievale 38, 409–430.

Vroom, J.A.C., 2014. Byzantine to Modern Pottery in the Aegean. An Introduction and Field Guide, Second and Revised Edition. Turnhout: Brepols.

© Mink van IJzendoorn and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Mink van IJzendoorn and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.