The Measure of Things: on the Size of a Loaf or the Length of a Poniard

Although easily overlooked, the facades of many churches and public buildings show up iron rods or studs, carved shapes like the contours of feet or daggers, and even representations of bricks and floor tiles. These signs hark back to a time when standard measures differed from place to place.

Before the implementation of the metric system during the Napoleonic era, measures were not standardized. The Paris ell, for example, was 1,884 meter long, while in Provins it was no more than 0,826 meter. The length of the ell could also vary according to, for instance, the type of cloth to be measured. The foot or shoe was derived from the fathom, the span between a man’s outstretched arms. One fathom generally measured six feet. The measure of a foot could therefore show up considerable differences. This variation in measures caused the sixteenth-century Florentine historian Vincenzo Borghini to exclaim: “The nature of weights and measures is both very uncertain and very unstable. They vary from moment to moment, place to place and thing to thing, so much so that to reduce them to a fixed and equivalent term is very difficult, if not impossible.”

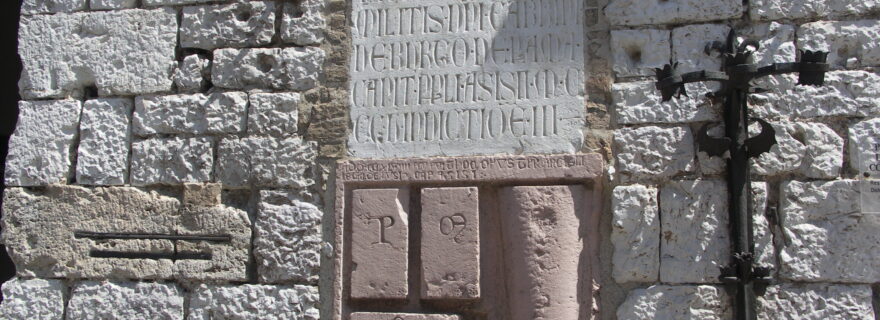

To ensure that buyers and vendors were familiar with the standard measures current in a certain place, these were carved onto or displayed on church facades in such a way that they could not be removed or tampered with. The church of Brélévenez (Brittany) has a stone with a large container carved into it that could hold some 70 litres, which bears a twelfth- or thirteenth-century inscription that reads: “This is a measure of grain that will not disappear.” The church was a good place for such measures as, after all, the biblical Book of Wisdom (11:20) teaches that God “disposed all things by measure, number, and weight.” Whoever tampered with the measures, tampered with God. From the thirteenth century, in concord with the development of towns and cities, measures also came to be displayed on city gates, town halls, market buildings, and other public spaces. In order to make sure that the measures used by merchants and vendors adhered to the rules, inspectors were nominated.

A splendid example of a series of standard measures being applied to a façade is provided by the Assisi’s thirteenth-century Torre Civica. The measures include various units of length (a yard, a foot and a palm), and the respective standards for the thickness and size of roof tiles, bricks and floor tiles. The display of such standard measures was not only practical, it also advertised that the governing authorities took care to ensure fair trade standards.

All sorts of measures could be found on facades. In the porch of the west tower of the collegiate church of Freiburg im Breisgau, there is, amongst other measures, the required size of a loaf of bread, dating to c. 1270-1320. On the church of St George in Haguenau (in the northern Alsace), the vertically placed measure of an ell and fathom are accompanied by the measure of a blade, all carved into one of the buttresses on the street-facing south side of the church. According to the city’s fourteenth-century custom’s book (Statutenbuch), the length of the blades of the poniards that the city’s bourgeois were allowed to carry around was not to exceed the one shown in the carving on St George’s Church. It is alarmingly large. Another example, equally large, is to be found on the northeastern buttress of the belfry (Kapellturm) of the small town of Obernai, where it is accompanied by the Obernai ell.

An early example of placing the prevalent standard measures on churches is provided by the southeastern wall of the cathedral in Bamberg (Germany). Next to the so-called Gnadenpforte, at irregular intervals and just below eye-level, there are three iron studs in the form of lion’s heads that represent some of the measures used in the city and part of the bishopric of Bamberg until 1811. The span from the first head (left) to the second head (middle) is in fact the Bamberg ell (67 cm). To the right of the third head the shape of a shoed foot gives the measure of the Bamberg foot (26,6 cm). It is thought that these little heads, dating after 1230, are the oldest existing medieval measurement units to have survived. The same combination, ell and shoe is to be seen on the exterior of the thirteenth-century church of St Mary in Gelnhausen.

In the famous abbey of Saint Denis near Paris a whole range of standard measures (bushels) was on display against the north wall of the western narthex that would be seen by anyone entering the abbey church via the north portal of the facade. From the style of the inscriptions, they too appear to have been of the medieval period, some even dating to the twelfth century. Officers carried out unannounced inspections to ensure that the measures used in commerce complied with the standards displayed within the abbey. If they did not, the merchant could expect a substantial fine. The standard measures were destroyed around 1740, but descriptions and drawings give us an idea of what they looked like. A drawing by Ph. Buache of c. 1740 shows the Saint-Denis ell in the lefthand corner, placed upright against a pillar. In front is an octagonal shape, inscribed: ‘Veci la demi mine au guede’, a measure for woad, a colouring used to dye clothes blue made of a plant named Isatis tinctoria which was grown on the Saint-Denis estate and was an important source of income until the end of the fourteenth century. The inscription is repeated below the drawing and shows the official abbot’s crook to the left. Next comes a round sort of bushel of uncertain usage. Then, mounted into a rectangular base which brought it within easy reach of the user and at the same time guaranteed that it could not be taken away, are three bowls with the measures of ‘adnone’, ‘sel’, and ‘ole’. ‘Adnone’ was a mixture of wheat, rye and barley. ‘Sel’ was salt, and ‘ole’ was some form of salt mixture. Salt was important for the monks as they had to right to impose a tax on all salt that was traded on their lands.

Although the measures in Saint-Denis have long gone, in the Loggia dei Mercanti of the basilica of San Benedetto in Norcia the measures and bushels are still in place. Those of Rome’s Campidoglio market, that was once located in the space between the Palazzo dei Conservatori, the Senatorial palace and the church of Sta Maria in Aracoeli, also have survived and are now in the Capitoline Museums. The earlier measures (congi) take the shape of a small 122 cm high marble column (that looks as if it was carved from a fluted Roman column) with lion head flanked by two smaller such heads on the principal side. There is also a ‘rugitella’ (a measure for grain). Around 1300, two new ones were added, one representing the measure of oil, the other of one the measure of wine. These are shaped like small square piers, 119 cm in height, that support large heraldic shields on its sides, as well as an inscription just above the base indicating its intended usage.

Another product that required standardizing was building materials like bricks. When the economic surge accelerated building in stone, bricks were gradually reduced in size, as smaller bricks took a shorter time to fabricate and were easier to handle. However, when using bricks in large building projects they needed to all be of the same size. Standardization of the measure of a brick was therefore in order, the more so as many cities required the houses within their boundaries to have walls with a thickness of at least 1,5 to 2 brick lengths to reduce the risk of conflagration. Standard measures for bricks were therefore devised. In the northern Netherlands the earliest example of this comes from Utrecht and dates to 1342. It warns that any man or woman involved in firing brick within the freedom of the city or in places under the city’s protection that does not conform to the town’s standard measure will be required to pay a fine of five pounds per oven (Enich man of wijf, de steen bornt binnen der stat vrijheyt of binnen der stat bescermnisse ende deen steen minre vormde dan der stat vorme, die verboerde van elken oven, dien si bornden vijf pont). The standard measures were displayed in or in front of the town halls for all to consult. The civic measure fort brick in Ghent was kept in the Ghent town hall as early as 1371. The Leiden Lakenhal still possesses three different iron measures for brick from the town hall that were suspended from the façade with iron chains.

When the metric system was introduced and measures became standardized, the old measures became redundant. Interestingly, in France, several of the former volume measures were given a second life as holy water stoops, as for example a specimen in the church of Château-Landon. Here then, in a neat sort of way, what came from God was returned to God.

Literature

J. Hollestelle, De steenbakkerij in de Nederlanden tot omstreeks 1560, proefschrift universiteit van Utrecht, Assen 1961, 81-95.

A. Lombard-Jourdan, ‘Les mesures-étalons de l'abbaye de Saint-Denis’, Bulletin Monumental 137-2 (1979) 141-154.

E. Lugli, Measuring in the Renaissance: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press 2023.

E. Zinner, ‚Alte Maße an Kirchen und Rathäusern‘, Bericht der naturforschenden Gesellschaft Bamberg 37 (1960) 17-19.