The Moving Finger: Glimpses into the Life of a Persian Quatrain

How did the Rubáiyát attributed to the medieval philosopher Omar Khayyam find its way on board of the R.M.S. Titanic, into a parody of Mark Twain, and even into a speech of President Bill Clinton?

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

بر لوح نشان بودنیها بودهاست

پیوسته قلم ز نیک و بد فرسودهاست

در روز ازل هر آنچه بایست بداد

غم خوردن و کوشیدن ما بیهودهاست

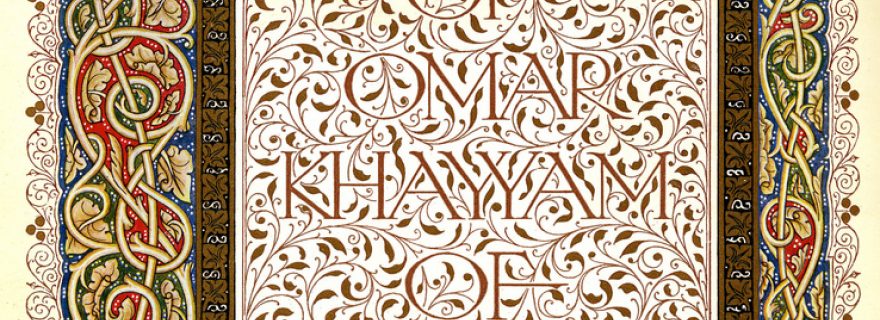

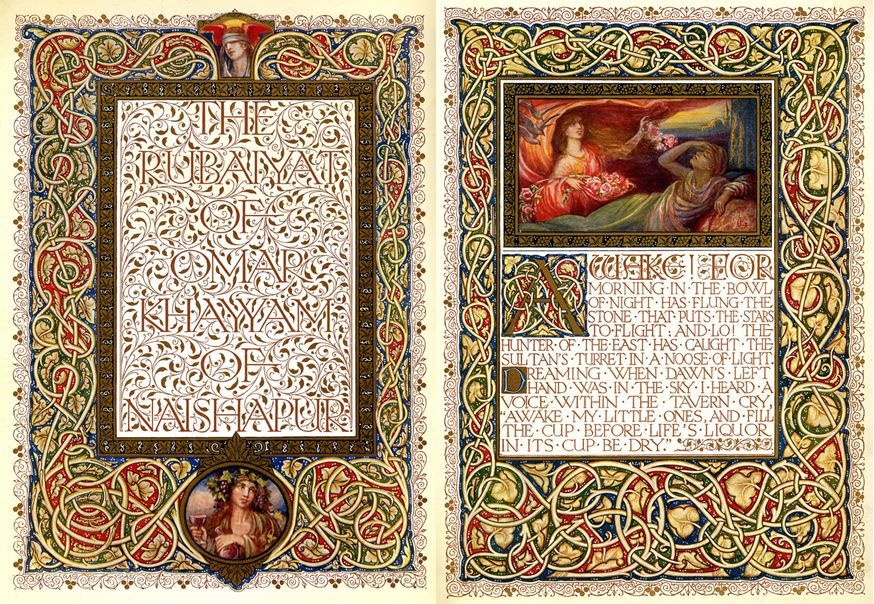

This quatrain is put on the walls of the Leiden Institute For Area Studies (LIAS) at Leiden University to enhance the buildings at M. de Vrieshof. The poem is one of the many quatrains attributed to the Persian astronomer and philosopher Omar Khayyam (c. 1048-1131) which inspired Edward FitzGerald (1809-1883) to make his adaptation, The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám in 1859. The authenticity of quatrains ascribed to Khayyam is a matter of contention as the majority of these poems are attributed to him in later centuries. FitzGerald’s adaptation of the Persian quatrains inspired generations of artists, poets, philosophers and politicians, who used the poems in a wide range of contexts. The quatrains possess an air of mystery. They are terse in contents, and witty in the universal wisdom they express, but also hedonistic in worldview, strongly propagating the carpe diem philosophy. It is this combination that has made the quatrains so popular for generations of readers in different cultures. FitzGerald’s rendering is unique in translated literature, inspiring more than a thousand poets to prepare their own translations in various languages. The Rubáiyát became a cult in Europe and America at the turn of the twentieth century, and later in the rest of the world as well.

The Cult of the Rubáiyát

Although these quatrains have become one of the best-known poems in the world, the publication of the first edition was a failure. FitzGerald translated seventy five quatrains, published 250 copies, and he himself bought forty copies. The books were sent to Bernard Quaritch’s bookshop, but they would not sell. The bookshop put them outside the door in a box for sale. Whitley Stokes and John Ormsby discovered the book in 1861. Stokes bought several copies of the Rubáiyát for his friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a member of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. The Pre-Raphaelites received the translations positively, which led to the publication of a second edition of the Rubáiyát in 1868. This second edition contained 110 quatrains. John Ruskin, one of the Pre-Raphaelites, wrote to FitzGerald in euphoria on 2 September 1863:

My dear and very dear Sir,

I do not know in the least who you are, but I do with all my soul pray you to find and translate some more of Omar Khayyam for us. I never did – till this day – read anything so glorious, to my mind, as this poem … and that, and this, is all I can say about it –

More – more – please more – and that I am ever Gratefully and respectfully yours.

The Rubáiyát ran to the fifth edition (1872, 1879), the final one was published posthumously in 1889.

The quatrains are probably one of the most translated literary works from a medieval Islamic culture. They are translated in almost all major languages of the world. Several of FitzGerald’s coined phrases have become proverbs in English such as “Take the Cash, and let the Credit go,” or “A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread—and Thou,” which comes from the following quatrain:

A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread—and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness—

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!

The vogue of the quatrains did not limit itself to literary circles, which produced a large number of imitations, parodies, commentaries, but also to material culture where individual quatrains were cited in commercial advertisements for tobacco, cigarettes, pencils, coffee, chocolate, perfume, toilet soap, wine, cafes, calendars, and many other objects. There are many reports about soldiers in both World Wars who kept copies of the Rubáiyát in their pockets and knew the quatrains by heart. Coumans gives 1015 editions of Edward FitzGerald’s translations in his recent bio-bibliography. It is amazing how these quatrains have reached such a sensational popularity.

R.M.S. Titanic and the Rubáiyát

Paradoxically the sensation for the Rubáiyát even increased when it went down on board of the R.M.S. Titanic. One of the most lavished publications of a book is by Sangorski & Sutcliffe who worked on this edition for two and a half years. This was how The Great Omar – A Copy of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám was created. The commissioner, John Stonehouse, had given the following instruction: “Do it and do it well; there is no limit, put what you like into the binding, charge what you like for it; the greater the price, the more I shall be pleased; provided only that it is understood, that what you do, and what you charge for, will be justified by the result; and the book when finished is to be the greatest modern binding in the world; these are the only instructions.” (Shepherds, 49) The binding contained thousands of jewels. The front board was adorned with three peacocks beneath a Persian arch, perching upon the “shape of a heart,” their tails made of inlaid jewels and gold, almost taking up the entire cover. “The eyes of the feathers were set with topazes, 97 in all, (…), the crests of the birds were decorated with 18 turquoises and their eyes were set with rubies.” (Shepherds, 53-56) The American Gabriel Weis purchased the book at an auction. Sotheby packed and sent the book to New York on the Titanic. Sadly the book now lies probably on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

The Moving Finger

Going back to our quatrain “The Moving Finger,” it is one of the favourite poems in the English speaking world. A search on Google for “Omar the Moving Finger” offers 940.000 results, and searching only “the Moving Finger” yields to 74.000.000, pointing among others to Agatha Christie’s 1942 novel The Moving Finger. To my knowledge, the poem was used in the United States by Martin Luther King (1929-1968) and President Bill Clinton (Pr. 1993-2001). Martin Luther cites Omar Khayyam in his speech “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence” in 1967 to refer to the inexorable passage of time, “We may cry out desperately for time to pause in her passage, but time is adamant to every plea and rushes on. Over the bleached bones and jumbled residues of numerous civilizations are written the pathetic words, ‘Too late.’ There is an invisible book of life that faithfully records our vigilance or our neglect. Omar Khayyam is right: ‘The moving finger writes, and having writ moves on.’” Clinton cited the quatrain during the Monica Lewinsky affair in 1998, “Like anyone who honestly faces the shame of wrongful conduct, I would give anything to go back and undo what I did. But one of the painful truths I have to live with is the reality that that is simply not possible.” Afterwards, he cites the quatrain.

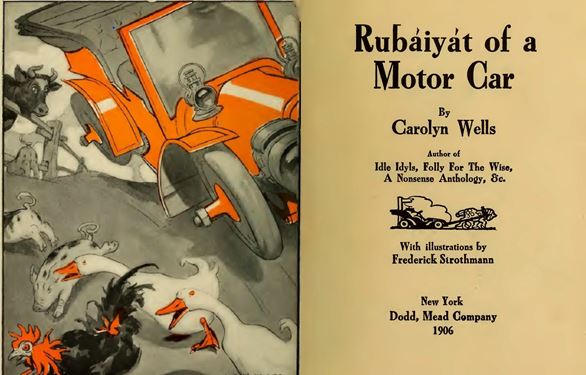

Burgeoning Parodies on The Rubáiyát

The popularity of the Rubáiyát inspired a wide range of poets and artists to make parodies of the quatrains. Famous authors such as Mark Twain (1835-1910) wrote parodies varying from the discomfort of old age to losing sexual powers, or staying in bed when the sun rises, instead of FitzGerald’s advice, “Wake! For the Sun, who scattered into flight …”. The founder of the Dutch Omar Khayyam Society, the late Jos Biegstraaten is perhaps one of the few people who collected a large number of these precious editions and wrote scholarly essays about these fascinating poems. There are also several parodies on The Moving Finger which I cite here, thanking Jos Coumans for providing me with these specimens:

The legal Finger writes; and having writ,

Moves on and neither Thirst nor

Wit Has lured it back to cancel half a line

To give a Man excuse for being lit.

(The Rubaiyat of Ohow Dryyam - J.L. Duff)

"'The Moving Finger writes, and having Writ

Moves on.'" "And surely, dear, you have the Grit

To be submissive to the Hand of Fate,

When you can’t help yourself a single Bit."

(The Rubaiyat of a Huffy Husband - M.B. Little)

The Moving Motor speeds, and having Sped,

Moves on. Nor all the Cries and Shrieks of Dread

Shall lure it back to settle Damage Claims;

Not even if the Victims are Half Dead!

(The Rubaiyat of a Motor Car - C. Wells)

To conclude, FitzGerald has made Khayyam’s quatrains part of world literature, expressing how to live well, reminding us of our mortality, and why we should pluck the moment with a smile from the inexorable passage of time.

References and further reading:

Aminrazavi, M., The Wine of Wisdom: The Life, Poetry and Philosophy of Omar Khayyam. Oxford: Oneworld, 2005.

Biegstraaten, J., “Omar with a Smile,” in Persica: Annual of the Dutch-Iranian Society, No. 20, 2004-2005, pp. 1-37.

Coumans, J., The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: An Updated Bibliography, Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2010.

Karlin, D., FitzGerald Edward: Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Seyed-Gohrab, A.A. (ed.), The Great Umar Khayyam: A Global Reception of the Rubáiyat, Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2012. (digitally available at http://www.oapen.org/search?keyword=khayyam)

Shepherd, R., The Cinderella of the Arts. A Short History of Sangorski & Sutcliff, London and New Castle, DE: Shepherds and Oak Knoll Press, 2015.

© Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.