The walking dead: Fear of the supernatural in the Italian novella

“Varied and strange indeed are the terrors that the dead give the living."

According to Masuccio Salernitano (1410-1475), a writer from Salerno, ghost stories were nothing more than the result of foolish superstition. At night, when darkness surrounds us and we are unable to distinguish one thing from another, our fear lets our imagination run wild, and we make up “the strangest stories that man ever heard” to account for what we see. Even though Masuccio liked to believe that superstition only prevailed amongst the common folk, the Roman Catholic doctrine on Purgatory and the afterlife did allow for the belief in these occurrences: lost souls unable to find peace could look for help from the living, asking for their pity and their prayers. Numerous accounts about fear of the walking dead can be found in the stories of Italian novella writers like Masuccio himself, ranging from comedy to tragic horror tales.

The lady in white

.jpg)

Illustration by Harry Clarkes for Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination (1919-1923)

In one of Antonfrancesco Grazzini’s (1505-1584) most macabre stories, two priests use the corpse of a beautiful young woman to scare each other – with fatal results. The tale starts with Piero, who for comical purposes decides to remove the woman’s body from her tomb and tie her up in the church. When Mico enters the dark church by night, guided only by a candle, his shoulders suddenly touch the feet of the dead girl, who was “tied up and hanging from the bell rope by her own tresses”. He recognized her immediately, “by her long, blonde hair and the crown of assorted flowers on her head”. Frightened out of his mind, he runs away, and tries to leave the church, only to find that the doors are locked. Once he has calmed down, however, he at once suspects the scene to be a prank, and plots his revenge. Piero, satisfied with the effect of his joke, returns to his dormitory and falls into a deep sleep – unaware of Mico’s short visit to his room. It is already morning, when he wakes up and notices the dead woman lying next to him.

Turning over in his bed, not yet well awake, his hand touches her face, and finding it soft and colder than marble, he immediately pulls it in, and full of wonder and fear opens his eyes, and sees the dead woman, and remembering that what he had done, he didn’t doubt that she had come here to strangle him.

Frightened out of his mind and hurrying to get away from the corpse, Piero falls down a stairs and breaks his arm. When he is found, he is carried to the house of some neighbors, to whom he explains what had happened to him. In the meantime, however, Mico takes the corpse from his bed and reburies it, so when the neighbors enter Piero’s room, it is empty, and they tell him that he must have dreamt it. Piero, however, still believes that what he has seen is true, and suffers so much from melancholy that he stops eating and drinking, and finally, in a moment of despair, throws himself from a window.

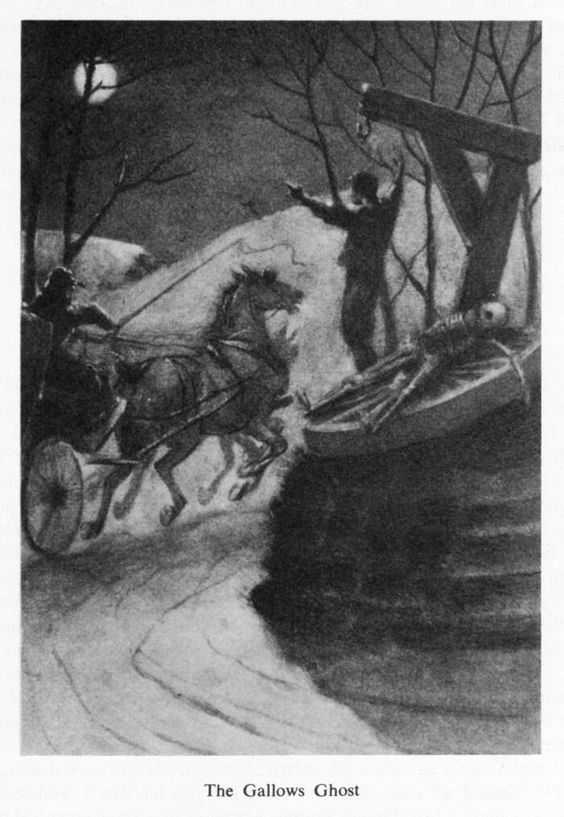

The hangman’s curse

The Gallows Ghost by Philip Burne-Jones (1895). Illustration for Johannes Wilhelm Meinhold’s Amber Witch

The fear of dead people coming back to life can be found in the tales of other Italian authors as well – although these are of a much more comical nature than Grazzini’s Edgar Allan Poe-esk gothic horror tales. In a novella story by Masuccio Salernitano, a company of men from La Cava travels to Naples. One of them can’t keep up with the pace, and falls behind. Overcome by nightfall, he falls asleep at the Ponte Ricciardo. A tailor from Amalfi, following the same road, falls asleep not far from the man from La Cava. Just after midnight, he wakes up, and thinking that it is already dawn because of the brightness of the moon, he sets out to continue his journey. It is only when he passes a monastery and hears friars singing the matins (about 3 a.m.) that he realizes it is still night. Moreover, he with a shudder becomes aware of his surroundings: he was close to the Ponte Ricciardo where it was custom to hang criminals. The tailor became very afraid (according to Masuccio, “because he came from Amalfi, where men are known to be timorous and faint-hearted by nature”) but continued his path.

Being thus bewildered and filled with fear (for it seemed to him with every step that one or other of the hanged corpses must be on his traces), he came close to the spot the thought of which had struck him with such great terror. Then, when he had come face to face with the gallows, and noticed that none of the criminals on it stirred at all, it seemed to him that by this time he had left behind the most pressing part of the danger, so that, awakening some of the bravery which was within his breast, he cried: “Aha, master gallows-bird! Will you go with me to Naples?”

At this cry, the man from La Cava wakes up and believing that this is one of his companions who has come back for him, answers: “Here I am, I will soon be with you”. The tailor from Amalfi almost dies from terror, thinking that he is greeted by the corpse of the hangman, and flees from the scene as fast as he can, shouting for help. The man from La Cava, however, immediately goes in pursuit, as he now believes that his companion is being attacked. His words of comfort, “Here I am, I am coming for you. Wait for me, do not be afraid”, of course only serve to strike even greater terror into the heart of the fugitive. It is only when the man from La Cava finds the bag full of valuable market ware that the poor tailor has thrown away, that he realizes his mistake. Picking up the bag, he rejoins his companions and they set out for Naples once more. Meanwhile, the tailor from Amalfi arrives at a tavern and sobbingly tells his story, which in a few days is spread throughout the country. “And it was told as a sure and certain fact how the corpses of the men who had been hanged were wont to chase any lonely traveler who crosses the Ponte Ricciardo, and because of this, no peasant would go by that spot before daylight without first having signed both his beast and himself with the cross”.

A corpse, a priest and a monkey

.png)

Lucas Horenbout’s miniature portrait of Catherine of Aragon with her pet monkey (1525)

If Masuccio’s hangman-story was already a comedy of errors, Matteo Bandello’s Novelle include a story about the walking dead that is even more whimsical. According to Bandello, Duke Ludovico Sforza of Milan had a very big she-ape (a “simia”) who often played at the house of a neighboring widow who was very fond of her. Eventually, the widow falls ill and dies and is carried off for burial, but while everyone is at the funeral, the ape puts on the widow’s head-dress (a bonnet with ribbons) and climbs into the bed, covering herself up with the blankets as if she were the widow herself. When the funeral company returns to the house, the maid who finds the ape cries that the dead woman has returned to her bed. The lady’s sons immediately send for the parish priest, who tries to calm them, saying that this must be an illusion, but that he will nevertheless try to exercise and expel any evil spirits. After having sprinkled the entire house with holy water, the priest goes to the bedroom, assisted by his clerk.

When he came into the room and saw Madame Monkey, who lay there in a very demure manner, he thought that she was the dead and buried woman and started to feel a little frightened; nevertheless, gathering heart, he came closer to the bed and raising the aspergillum [holy water sprinkler], started saying “Asperges me, Domine” and throwing water on the ape. She, seeing the priest waving the aspergillum as if he was going to beat her, started to show her teeth and grind them together. The priest, seeing this, now firmly believed that she was some evil spirit and became very afraid, and dropping the aspergillum, he fled the scene. However, preceded by his clerk, who had thrown down the cross and holy water and fled away downstairs in such a hurry that he stumbled, and as the priest fell over him, they both went head over heels.

Trembling, the priest announces to the widow’s sons that he has seen the devil in the shape of their mother, while meanwhile, the ape climbs down the stairs. Seeing the ape wearing the widow’s bonnet and wrapped up in some pieces of linen, one of the sons finally realizes that his mother looked much less ape-ish before. Once everyone sees through the piece of theatre, they realize their mistake and “fear was changed into laughter”.

Further reading:

- M. Papio, ‘MasuccioSalernitano’s Gusto dell’orrido’ in: G. Allaire ed., The Italian Novella. A Book of Essays (New York/London 2003) 119-136.

- R.J. Rodini, Antonfrancesco Grazzini. Poet, dramatist, and novelliere, 1503-1584 (Madison WI 1970).

© Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.