There was a Door to which I found no Key

The quatrains of Omar Khayyam, in Edward FitzGerald’s adaptation, have a special appeal worldwide. In this blog, the English adaptation of one of the most popular quatrains is compared to the original Persian. How has Khayyam’s worldview been translated?

The Authenticity of Khayyam’s Quatrains

Quatrains treating subjects such as wine, carpe diem, criticism of God’s creation and the Hereafter are commonly ascribed to Khayyam (ca. 1048-1131), but most are from later centuries. Mystics, philosophers and poets ascribed quatrains to Khayyam from the 13th century. The Persian original of this particular quatrain does not appear among the oldest surviving quatrains: it is found in the collected poetry of Nâser Bokhârâ’i, a fourteenth century poet. Khayyam’s quatrains, such as the following, were cited by mystics such as Râzi, accusing him of materialistic philosophy:

Why did the Owner who arranged the elements of nature

Cast it again into shortcomings and deficiency?

If it was ugly, who is to blame for these flaws in forms?

And if is beautiful, why does he break it again?

Khayyam’s Persian Worldview

Before analyzing the poem, I will present the original and a literal translation:

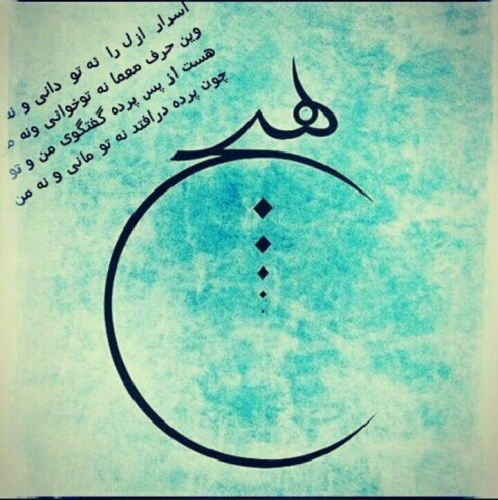

اسرار ازل را نه تو دانی و نه من

وین حرفِ معمّا نه تو خوانی و نه من

هست از پس پرده گفتوگوی من و تو

چون پرده برافتد، نه تو مانی و نه من

asrâr-e azal râ na to dâni-yo na man

v-in harf-e mo’ammâ na to khâni-yo na man

hast az pas-e parda goftegu-ye man-o to

chun parda bar oftad na to mâni-yo na man

Neither you nor I will know the secrets of eternity

Neither you nor I will read this letter of the riddle.

The dialogue between you and me is behind the veil,

When the veil falls, neither you nor I will remain.

The word azal in the first line refers to eternity a parte ante, in contrast to abad or eternity a parte post. Persian poets link azal with God’s creation. Here the poet refers to the moment when God created the world. It is also called the day of alast, referring to the Koranic phrase “Am I not thy Lord?” (alastu birabbikum) to which the loins of Adam answer, on behalf of the human race, “Yes we witness thou art.” The moment of the creation is presented in this line as a secret to which we have no access. In the second line, the poet repeats this idea, using a synonym for the secret, namely mo‘ammâ, a riddle or enigma. This enigma is presented as a compound harf-e mo‘ammâ, which means both ‘talk about the riddle,’ or ‘a letter of the riddle,’ pointing to letter symbolism. In Persian poetry, God is sometimes depicted as a Writer, the creation as letters, and the entire cosmos as a book. The word “pen” also appears in the Koran (68:1) and the hadith. God writes all the events of the world from beginning to end. Based on this image, God is also referred to as a painter, as in the following verse from Hafez (1315-1390):

خیز تا بر کلک آن نقاش جان افشان کنیم

کاین همه نقش عجب در گردش پرگار داشت

Rise that we may sacrifice our souls to that Designer’s pen:

So many wondrous designs he had, in the circling of his compass.

Orthodox Muslims might read Khayyam’s quatrain as blasphemy because the poet claims that we cannot fathom the reasons behind God’s creation. According to orthodox Islamic teaching, God created the world with a clear purpose, namely for man, so that he may worship God, perform good deeds, and return to eternal life in the Hereafter. Often the agricultural metaphor is used to indicate the temporality of this world in relation to the eternal nature of the Hereafter and why we should use this world to prepare ourselves for the hereafter: al-dunyâ mazra‘at al-âkhera, or “the world is the field for the Hereafter.” A mazra‘a is a field that has been sown, or in this case, that is ready to sow. God has also given man a special position as his vicegerent on the earth, a responsibility that the angels did not dare to accept.

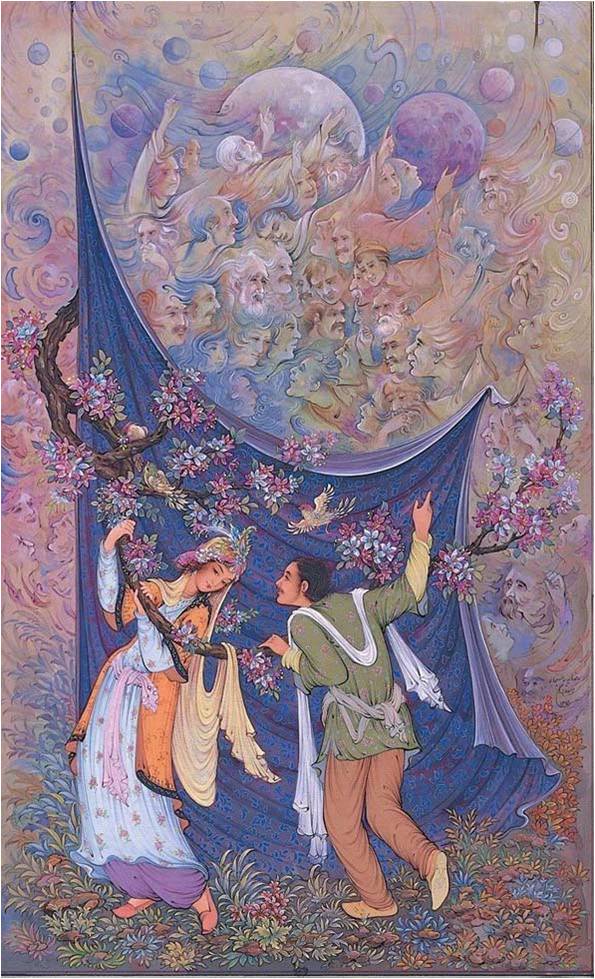

In a Sufi context, the purpose of creation is also clearly defined. According to Sufis, God consciously created the world out of love for man. God wished to reveal His beauty; therefore he created man in His own image. In a Sufi context, the secrets of the first line would refer to man’s love relationship with God. At the primordial moment (azal), God created man and breathed the soul into his body. God places all his secrets in man’s heart, enabling him to understand His secrets through intuition. This intuitive ability is diametrically opposed to reason, or the intellectual reasoning associated with philosophers.

While the first two lines of the quatrain introduce the subject, the third line, “The dialogue between you and me is behind the veil,” prepares the answer that follows. Here the poet refers to man’s endeavors to unravel the secret of the creation. He quickly realizes that all the attempts of the philosophers to solve the riddle remain on this side of the ‘veil,’ giving no clue as to what is happening on the other side. The word parda, which I have translated here with ‘veil’, has diverse meanings. One of these is the veil that separates the visible world from the invisible spiritual realm. From the visible world one can never fathom the secrets of the invisible, not by the aid of reason as philosophers do, nor with intuition as the Sufis believe. They too remain on this side of the parda. The intellect is part of the infinite Whole and as such it can never grasp the Whole. In the fourth line, the uncompromising answer is given: only when the veil falls, a metaphor for death, can one access the other world: no one has brought news about the other side of the veil.

FitzGerald’s Reworking

FitzGerald’s (1809-1883) adaptation of this quatrain is splendid, introducing other dimensions in this poem. It is the 32nd quatrain of the first edition:

There was a Door to which I found no Key:

There was a Veil past which I could not see:

Some little Talk awhile of ME and THEE

There seemed - and then no more of THEE and ME.

As in the quatrain attributed to Khayyam, FitzGerald chooses the pronoun “I.” The notion of the primordial moment is not mentioned; FitzGerald broadens this notion to a generalized knowledge or secret that man cannot access. The closed door emphasizes man’s impotence. The search for the key alludes to man’s curiosity to gather new knowledge. By evoking the image of the door and the key, FitzGerald prepares the reader to interpret the veil as a tangible blockade. The ‘Veil’ is a different concept in Persian than in English. In Persian usage, a veil is not transparent, and separates spaces. In English, the association of a veil is mainly to a light semi-transparent material that is easy to put aside. So FitzGerald actually uses the word in an un-English manner. The impotence of man is further underscored by the sensory verb ‘to see.’ Without a key, the door cannot be opened, and the I-persona cannot see what is hidden behind the veil. Persian does not use capital letters, but the context makes it immediately clear that it is about God’s secret, while FitzGerald uses capital letters for ‘door,’ ‘key’ and ‘veil.’

In the last two lines, FitzGerald emphasizes the ephemerality of man’s existence, whereas Khayyam concentrates on the secret of eternity. The English version states that there is talk about you and me for a while, and that we will be forgotten afterwards. FitzGerald clearly chooses to emphasize man’s transient nature, the fleeting time, and the inevitability of death. FitzGerald’s poem is part of a series of 75 quatrains depicting the life of an individual in one day. This poem then shows the impermanence of the world.

In the fifth edition, FitzGerald changed a number of elements to put more emphasis on life’s transience. The words ‘Door’ and ‘Veil,’ receive the definitive article ‘the,’ whereby these words are treated as archetypical entities the reader is assumed to know. The phrase "There seemed" has been replaced by the unconditional construction “There was,” presenting transience as an absolute fact:

There was the Door to which I found no Key;

There was the Veil through which I might not see:

Some little talk awhile of ME and THEE

There was—and then no more of THEE and ME.

As noted above, the Persian original is not from Khayyam. Like many others with themes such as sharp criticism of God’s creation, it is attributed to him. But in his philosophical treatises he presents a different opinion. We can contrast his approach to God and his creative capacity in the following passage to the way he treats the same topics in the quatrains:

Why did He create a thing, which He knew would be necessarily accompanied by non-existence and Evil? The answer is: Take Blackness for instance, in it there are a thousand goods and only one Evil. To abstain from a thousand goods for the sake of a single evil is itself a great evil, for the proportion of the good of blackness to its evil as one found in the creation of God is accidental and not essential. It is also evident that the evil according to the first Wisdom was very little, and that qualificatively or quantitatively it does not compare with Good. (An Anthology, 2008:479)

Thinking of Jos Biegstraaten, the first chairman of the Dutch Omar Khayyam Society, to whom I dedicate this piece, I would like to end this article with a smile, just like Jos, who had a passion for both Khayyam and parodies. Mark Twain (1835-1910) wrote the following parody of the same poem:

There was the door whereof I had the Key,

The Landlord too, who double seemed to me –

Some heated Talk there was – and then, ah then

But Rags and Fragments were we – Me and He. (Biegstraaten, 2004-05: 24)

References and further reading:

An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia: From Zoroaster to ʿUmar Khayyām, Vol. I, ed. Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Mehdi Aminrazavi with the assistance of M.R. Jozi, London / New York: I.B. Tauris, 2008.

Biegstraaten, J., “Omar with a Smile,” in Persica: Annual of the Dutch-Iranian Society, No. 20, 2004-2005, pp. 1-37.

Mir-Afzali, S.A., Robâ’iyyât-e Khayyâm dar manâbe’-e kohan, Tehran: Markaz-e Nashr-e Dâneshgâhi, 2003.

Najm-al-Din Râzi, Mersâd al-ebâd, ed. M.-A. Riyâhi, Tehran, 1992.

Nâser Bokhârâ’i, Divân, ed. M. Derakhshân, Teheran: Ofoq, 1974.

© Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.