This pig is on fire: A late medieval pig in Leiden’s Pieterskerk

A late medieval painting on a pillar in Leiden’s Pieterskerk shows a pig, surrounded by flames. What is going on here?

A pig on a pillar

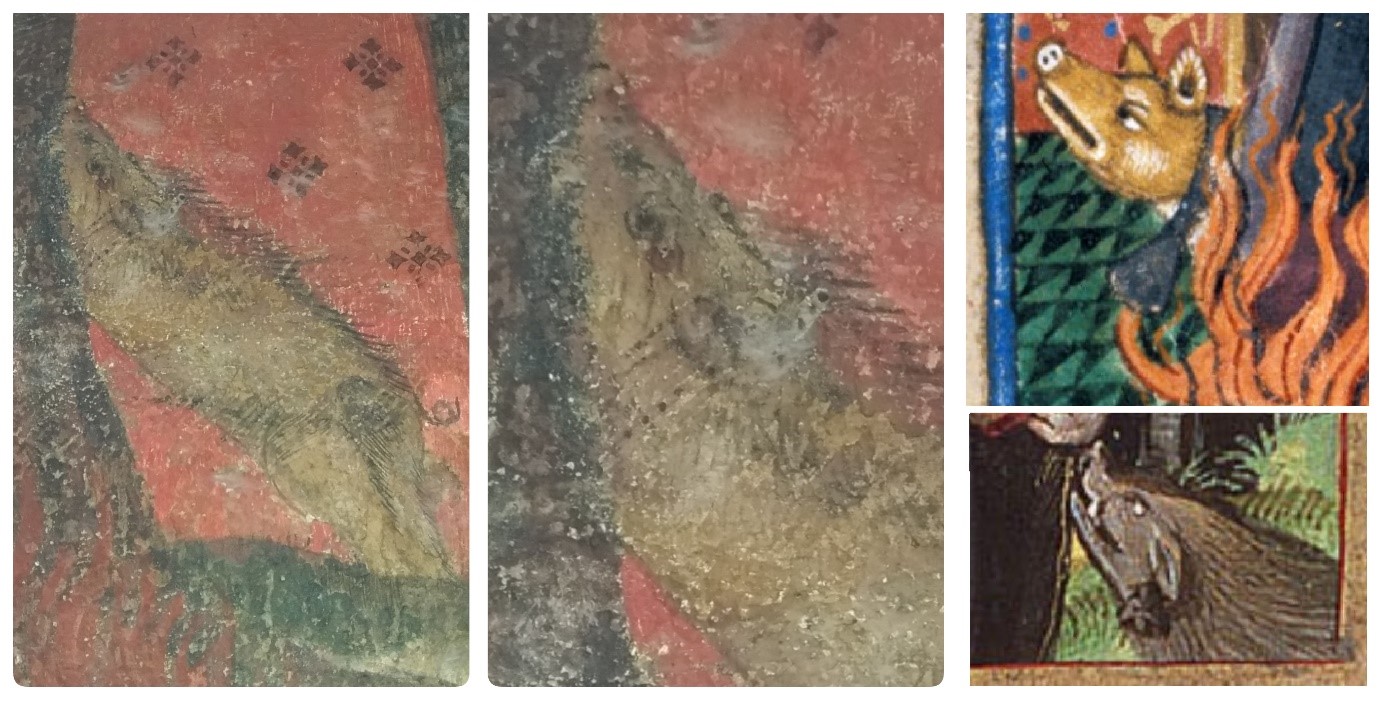

The Pieterskerk is one of Leiden’s medieval hotspots. The construction of the current late-Gothic church begun in 1390 and was completed around the middle of the 16th century. Much of its medieval interior was destroyed during the Great Iconoclasm in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, but some of it remains.On the pillars around the church’s choir, a number of early fifteenth-century paintings have survived. One pillar features the portraits of eight saints: St Peter (to whom the Church is dedicated), St Andrew, John the Baptist, St Matthew, Lanfranc (archbishop of Canterbury, d. 1089), Cornelius (a third-century pope), St Christophorus (carrying Christ) and a man with flames lapping at his feet, accompanied by a pig. This animal, as well as the flames, allow us to identify this man as St Anthony, the patron saint of pigs.

St Anthony the Great, patron saint of pigs

Anthony the Great (251-356) was a Christian monk who spent most of his life in the Egyptian desert, where he survived until the ripe of 105. Despite being exceedingly old, keeping to a moderate diet, never changing his clothes or even washing his feet, Anthony remained in good health:

And yet his health remained entirely unimpaired. For instance, even his eyes were perfectly normal so that his sight was excellent; and he had not lost a single tooth, only they had worn down near the gums through the old man’s great age. He also kept healthy hands and feet, and on the whole he appeared brighter and more active than did all those who use a diversified diet and baths and a variety of clothing. (Athanasius, The Life of Saint Anthony, trans. Meyer, ch. 93)

Saint Anthony’s story was first recorded by Athanasius, whose vita set a precedent that was followed in the hagiography devoted to various other hermits and desert fathers, who all lived long lives without feeling the pangs of age (see Porck 2019). Anthony’s cult flourished throughout the Middle Ages and the saint became associated, in particular, with skin diseases. For instance, Saint Anthony was often appealed to in cases of ergotism and erysipelas, both of which became known as "St Anthony’s fire". As a result, Anthony is often depicted among flames:

Various legends connect St Anthony to pigs. According to some, Anthony used to work as a swineherd, others claimed Anthony had a pet pig that helped him battle Satan, yet another legend suggests that Satan harassed Anthony in the form of a pig. Whatever the origin of the connection, Anthony is often depicted with a porky companion, as is the case on the Pieterskerk pillar:

Legal pigs in the city: Tantony pigs

A careful inspection of the pig on the Pieterskerk pillar reveals that it is wearing some sort of collar and, possibly, a bell in its ear. These attributes are in line with other depictions of St Anthony’s accompanying hog:

The bells on these pigs reflect the late medieval privilege enjoyed by the monastic order known as the Hospitallers of St Anthony. Named after St Anthony, these ‘Anthonine monks’ treated various diseases among the poor in medieval cities and, in order to feed their patients, they kept pigs (some of these pigs were donated to the order, the so-called ‘tantony pigs’). The Hospitallers of St Anthony were not the only ones to keep their swine inside urban areas and, by the fifteenth century, some medieval cities were so full of pork that measures were made to ban pigs from the streets.

Camphuijsen & Coomans (2015), for instance, describe how urban authorities in late medieval Holland hired officials to remove free-roaming hogs from urban areas for hygienic reasons; some cities enforced a strict two-pig-policy per household, while others established no-go-areas for pigs. The pigs belonging to the Hospitallers of St. Anthony were usually exempt from these regulation, as a reward for the order’s service to the city’s patients. In order to distinguish between illegal and legal pigs, the tantony pigs were given a bell or were branded with the so-called ‘tau cross’, also associated with St Anthony. With their little bells, these pigs were free to wander the streets without fear of being taken into custody.

Inspiration for a sixteenth-century Leiden artist?

Saint Anthony's temptation by demons in the desert was a popular theme in medieval and renaissance art, taken up by such artists as Jheronimus Bosch and Michelangelo (see, e.g., this overview). One early 16th-century painting has been ascribed to various artists working in Leiden, including Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), Aertgen van Leyden (1498-1564) and the so-called 'Master of the Kerkprediking' (information from the Jheronimus Bosch Art Center). Intriguingly, this Leiden artist, drawing his inspiration for some of the demons from Jheronimus Bosch's famous triptych, included Anthony's pig (absent from Bosch's triptych):

Could it be that the inclusion of this tantony pig was at least partly inspired by the fact that the artist worked in Leiden and would have passed by the painted pillar in the Pieterskerk on a regular basis?

Works referred to:

Athanasius, The Life of Saint Anthony, trans. R. T. Meyer (London: Longmans Green, 1950)

Camphuijsen, Frans & Janna Coomans, “De middeleeuwse stad en zijn varkens,” Madoc: Tijdschrift over de Middeleeuwen 29 (2015), 140-148.

Porck, Thijs, Old Age in Early Medieval England: A Cultural History, Anglo-Saxon Studies 33 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2019).

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.