Thou shalt not pass. Gender segregation in medieval churches

A dark line on the floor of Durham Cathedral prevented half of the medieval population from crossing it. What was it doing there?

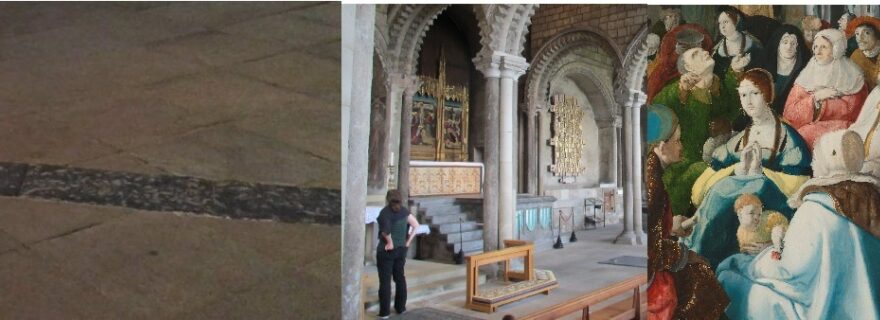

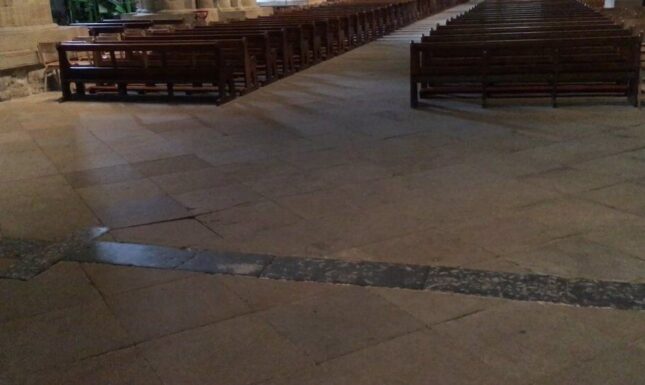

At the west end of Durham Cathedral, a little into the nave and near the main entrance porch, a dark black line made of the local Frosterly marble runs straight across the church’s pavement, from north to south. This line marked a boundary that women were not to cross. Women thus had no access to the shrine of the popular Saint Cuthbert, and were unable to enjoy the beauties of the cathedral’s architecture and interior fittings.

Durham Cathedral

Durham cathedral is one of the most magnificent medieval buildings in England. Towering above a high cliff along the river Wear, this church is one of the greatest manifestations of Norman supremacy to have been built in England in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of 1066. Together with the adjacent castle, the building brought home to the unruly north that the Normans had come to stay. The cathedral was famous for the shrine of St Cuthbert (c. 634-687),who had lived his life at the monastery of Lindisfarne and had died a recluse on the small island of Inner Farne. In 995, his relics were taken from Lindisfarne to Chester-le-Street and finally to Durham for safety reasons. With some 83 churches being dedicated to him, St Cuthbert was the most popular saint in the north of England.

St Cuthbert

As a miracle worker, Cuthbert thwarted the first attempts of the Norman invaders to conquer the region by conveniently-sent fogs and an opportune illness. In order to gain a permanent foothold in the north, it was necessary for the Normans to appropriate this cult of St Cuthbert by ousting the clerical community that had serviced Durham cathedral for generations, ever since their forebears had carried the coffin with the saint’s remains to Durham. The community was rich and highly-regarded. The clerks held lands, and had wives and families with whom they lived in the monastic precinct. After the first Norman attempts at gaining power in Durham had ended in outright butchery and disaster, King William the Conqueror sent the highly competent William of St. Calais to take matters in hand and in 1080 appointed him as the first Norman bishop of Durham. Within two years the Cuthbert community was replaced by a Benedictine monastery and, adjacent to the old cathedral, a new cathedral rose from 1093 onwards, which in time came to replace it. How the members of the Community and locals reacted to these changes is unknown, all the evidence we have for these huge changes come from the monk Simeon’s history of the church of Durham, that was very much written from a Norman perspective.

St Cuthbert’s misogyny

To force the women out of the monastic precinct, Simeon altered Cuthbert’s biography and made him into a misogynist, unable to abide women in the spaces where he had been buried. Simeon claimed Cuthbert’s dislike of women originated with the events unfolding at the monastery of Coldingham which had a congregation of both monks and nuns, living in different dwellings, but “they grew lax, and receded from their primitive discipline, and by their improper familiarity with each other, afforded to the enemy an opportunity of attacking them. For they changed into resorts for feasting, drinking, conversation, and other improprieties, those residences which had been erected as places to be dedicated to prayer and study”. God, of course, was angered by this and had the monastery consumed by fire. This shook them for a while, but soon they took up their old habits again. And so, when Cuthbert was elevated to the episcopal see, he decided to change the rules. From now on, the monks were to be secluded entirely from the society of women “apprehensive that the incautious use of that familiarity should endanger the purpose that they had in hand, and their ruin should afford the enemy cause for rejoicing. Men and women alike assented to the arrangement, by which they were mutually excluded from each other’s society, not only for the present but for all future time; and thus the entry of a woman into the church became a matter which was entirely forbidden”. For the women’s benefit, a separate church was erected nearby. At the end of the paragraph Simon added “This custom is so diligently observed, even unto the present day, that it is unlawful for women to set foot even within the cemeteries of those churches in which his body obtained a temporary resting-place, unless, indeed, compelled to do so by the approach of an enemy or the dread of fire”. Women were thus barred from the cult sites at Lindisfarne, Inner Farne and Durham Cathedral. That this was meant seriously is illustrated by several miracles performed by St Cuthbert. One lady taking a shortcut on her way home across the cemetery was struck dead; another woman, intent on seeing the “beauty of the ornaments of the church” and “unable to bridle her impetuous desires” got no further than the cemetery where she was deprived of her reason and ended up slitting her own throat. Later chroniclers provide even more examples of the saint’s singular wrath. Even a small girl trying to retrieve a ball from the precinct did not survive this transgression.

The power of money

In the end, the exclusion of women from the precinct came at a price as the cathedral started to lose income, especially when in the wake of the successful cult of Thomas à Becket rival cults were established all over England. In the north, the newly-established cult of Saint Godric at Finchale drew pilgrims away from Durham, the more so as women were welcomed there. This called for counter-measures and was one of the reasons for building the Galilee or Lady Chapel at the west end of the cathedral from 1175 onwards. In this chapel, that was completed in 1189, women were allowed to worship and pray. It was at this time also that the black demarcation line was made, indicating up to where women were allowed to advance into the cathedral proper.

Gender segregation in medieval churches

In order to better understand what was going on in Durham, it is useful to realize that the segregation of the sexes in church was quite normal in western Europe through the medieval period. Although it was not practiced by the earliest Christian communities, the phenomenon had become common by the fourth century. Around 380, Saint Augustine mentions the “seemly separation of the sexes”. William Durandus, writing in the thirteenth century, asserted that “the men are to be in the fore part, the women behind: because the husband is the head of the wife, and therefore should go before her.” It is even possible that the iconography of church furnishings was adapted to this principle. On the rood screens of English churches male and female saints are grouped together, sometimes on the south, sometimes on the north side, which may well reflect the seating arrangements for men and women inside the church. That seating arrangements varied from church to church is evidenced by the medieval sources. In the fifteenth century, benches in the parish church of St Peter’s in Leiden were located on either side of the nave, but in addition there were women’s benches near the south portal, on the south side of the nave near the pulpit as well as adjacent to the north portal. In addition, there was private seating. In the church of St George in Amersfoort a brown cross (bruyncruys) in the southern nave aisle acted as a sort of boundary, so it was ordained in 1465. Women were not to be seated in front of or next to it, risking a fine if they disregarded this rule, unless they had good reasons for their transgression. Neither were they allowed to sit on low stools. The same rule applied to the northern aisle, where women had to stay behind the statue of Our Lady holding the Dead Christ on her lap.

Art works confirm there were no set rules for the segregation of the sexes during sermons and mass. Fra Angelico’s painting of St Peter preaching to the Romans (Museo di San Marco, Florence), in contrast to Durandus’ assertion, has the women seated or kneeling on the floor around the saint in the pulpit, while the men stand around. St Mark has been given a chair, probably because of his old age, as evidenced by his grey hair and beard. We see the same arrangement in Fra Angelico’s fresco of St Stephen preaching in the chapel Pope Nicholas V built in the Vatican Palace. A similar scene in the Birmingham Museum of Art has all the men sitting on benches and the women kneeling, whilst attending a sermon by St Bernardino. However, an old woman on the front row has been provided with a bench. On the altarpiece of the church of St. Bernardino in L'Aquila (now in the Morronese Abbey, Sulmona), the men are all seated on benches on the left, while the women simply kneel on the floor to the right. Sano di Pietro’s painting showing San Bernardino preaching in the Piazza del Campo in Siena of before 1448 has the women in the audience on the left separated from the men by a cloth partition. In this painting both men and women are shown kneeling. Images of the Franciscan monk Savonarola preaching likewise have a cloth separating the men from the women, disabling eye contact. However, there are paintings that show somewhat more mixed audiences. ‘The Calling of St Anthony’ (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum) of c. 1530 has the men standing around a group of seated women, some of whom are sitting on low stools. Amongst the female audience there are also some male attendants, not all of whom are crippled or elderly. And what about Breughel the Elder’s ‘Sermon of the St John the Baptist’? There is no segregation here at all, men and women stand and sit side by side.

In all, although the measures taken in Durham Cathedral were extreme, the phenomenon of segregation was widely spread throughout medieval Europe and through time, even though practices differed. The subject has as yet not been widely researched and merits attention, the more because it may well have been influential on the layout of churches and the art works therein.

Select literature

B. Aird, ‘The Boundaries of Medieval Misogyny: Gendered Urban Space in Medieval Durham.’, in: L. Klusakova and L. Teulieres (eds.), Frontiers and Identities. Cities in Regions and Nations, Pisa University Press, 49-73.

Margaret Aston, ‘Segregation in Church’, in: W.B. Sheils and D. Wood, Women in the church: papers read at the 1989 Summer Meeting and the 1990 Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical History Society, 1990, 237-294.

John Field, Durham Cathedral. Light of the North, London 2006.

Adrian Randolph, ‘Regarding Women in Sacred Space' in: Geraldine A. Johnson and Sara F. Mathews Grieco (eds.), Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, Cambridge University Press 1997, 17-41.

© Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.