Throw Away that Tedious Text! 15th-Century Illustrated Books in 18th- and 19th-Century Hands

Studying fifteenth-century books can be a frustrating task, especially if former owners decided to throw away the text. But the changing attitudes towards early printed books are equally fascinating.

In our ‘Instagram-age’, we tend to think image-focused media as something contemporary. However, pictorial images have always played an important role in media, and the earliest printed books in Dutch are no exception. In the ‘new media’ of the late Middle Ages, images, in the form of woodcuts, were an important selling point. They did not merely embellish the book: woodcuts helped readers to find a certain section of a text (structuring tools), they conveyed (additional) information, and they functioned as meditative and emotion-arousing tools. At times, the images even seem to prevail in the use of these books since the narrative or information they convey can be accessed by anyone, regardless of their level of literacy.

Images and the Leeu Brothers

On the title page of his devotional booklet on the Seven Sorrows (i.e. the seven most painful moments in Mary’s life), the fifteenth-century printer Gerard Leeu (active in Gouda and Antwerp, 1477-1492) describes the function of the woodblocks he had made especially for this publication, as follows:

Ende tot elc van den seuen weeden so is ghestelt een figuer bi personagen die materie daer af bewisende, op dat die deuocie te stercker ende te meerder in den menschen verwect mach warden. Ende oec op dat die leeke liden die niet lesen en konnen, die personagien aensiende, hem daer inne oec sullen mogen oefenen, want die beelden sijn der leecker luden boecken. (Van de seven droefheden ofte weeden O.L.V., The Hague, Royal Library, 150 F 21, fol. a1r.)

[And to each of the seven pains a figure is set that represents the subject matter through characters, so that the devotion in people may grow ever stronger and greater. And also so that lay people who cannot read – looking at the characters [in the images] – may also exercise themselves therein, because images are the books of lay people.]

With a total of more than 900 woodblocks, Gerard Leeu, together with his brother Claes, was by far the largest supplier of woodcuts in the fifteenth-century Low Countries. He would have not suspected, however, that times would come in which the text he and his employees had painstakingly set and printed would be thrown away, while the work of the woodcutters that worked for him would be carefully preserved.

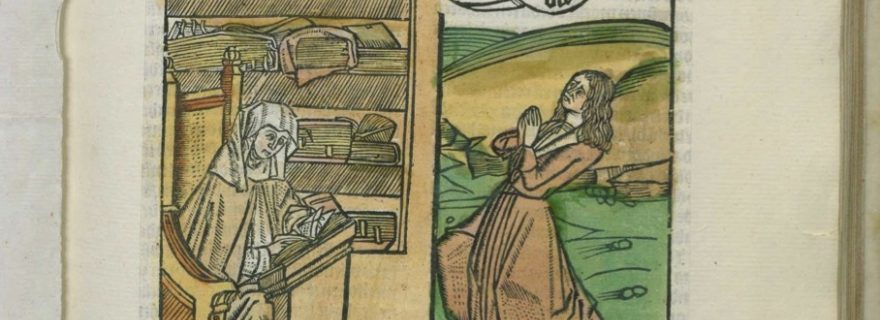

Some of Leeu’s most profusely illustrated books are the editions of the so-called Boeck van den leven Jhesu Christi (Book on the Life of Christ), which contains a dialogue between Man (the reader) and Scripture (a personification of the Bible (fig. 1)) partially based on the fourteenth-century Vita Christi by the Carthusian Ludolf of Saxony. Gerard used a large variety of woodblocks for these editions – some new, others reused – and his brother Claes added even more images and decorative borders to the second edition that appeared under his name in 1488 in Antwerp.

Cruelly Treated Copies

A copy of Leeu’s first edition (Antwerp, 1487), nowadays kept at the Rijksmuseum Catherijneconvent in Utrecht, presents an extremely frustrating object to scholars such as I, interested in the interplay between text and image, the materiality of the book, and the characteristics of individual copies. The copy stems from the collection of the Haarlem Bisschoppelijk Museum, and an ex-libris with a monk reading and a maxim from Thomas a Kempis, points to the Vondel and Bilderdijk specialist J.F.M. Sterk (1859-1941) as one of the former owners. It was an earlier owner’s behavior, however, that today appears inconceivable. The (English) owner explains the reasoning behind his approach to the book in an annotation in the front of the book. While the note is written with a pencil, which he still would be allowed to use in a Special Collections reading room today – even though not to actually write in the book – his other actions would clearly earn him a ban for life:

This book being already imperfect when I bought it, I threw aside all the leaves that had text only, and, retaining every leaf that had a cut, then send it to be bound. It will thus be found that every leaf has at least one cut.

One was now saved from leafing through all of those tedious pages on which Scripture and Man try to make sense of the History of Salvation, and could happily ‘swipe’ from image to image. Even though in 1884 the woodcut specialist Martin Conway remarked that ‘as far as their style and design goes, they are amongst the worst productions of a bad period’ (The Woodcutters of the Netherlands in the Fifteenth Century, 57-8), pages with at least one ‘bad’ image still had more appeal to this nineteenth-century owner than the pages with text only.

Cut-Out and Compare

While in this case the language might have been a factor in the decision to throw ‘the text aside’ (the image comes to mind of a nineteenth-century English gentleman sitting next to a fire place and happily feeding the pages with Middle Dutch text to the flames), the lawyer and incunabula collector Jacob Visser (1724-1804) did not have such an excuse. Visser applied a more laborious and commonly used method to his copy of the 1495 edition published in Zwolle by Peter van Os, in which Leeu’s woodcuts were reused. He cut out every single image, carefully getting rid of all the text.

The woodcuts were pasted onto blank leaves, creating a book of plates. Most plates are accompanied by a (more or less extensive) annotation that resulted from careful comparison with copies of various editions of the Boeck van den leven Jhesu Christi and other fifteenth- and sixteenth-century books in Visser’s extensive incunabula collection. With regard to a composite woodcut of a group listening to Jesus, Visser notes: ‘This plate is divided into two and in the edition of 1495 here shows Christ seated, while in the one of 1487 Christ is standing up’ [Deze plaat in tweën verdeeld zijnde vertoont alhier een zittende Christus in de editie van 1495, dog in die van 1487 is de Christus staande] (fig. 2).

Visser also gives some clues for the re-use of Leeu’s woodblocks in early sixteenth-century books. He notes that the woodcut of Scripture and Man was still in use in 1515 and that the woodcut that depicts Creation ‘has still served for a title page of a Bible printed in Antwerp by Claes de Grave in 1518’ [heeft nog gediend voor een Tytel van den Bybel gedrukt tot Antwerpen by Claes die Grave 1518] (fig. 3). Other images, such as that of the parable of the laborers in the vineyard, Visser found in his copy of Den grooten Cathoon vol vruchtbarigher leeringen historien ende exempelen, printed by Claes de Grave in 1535.

Even though in both cases valuable pages and material evidence were unquestionably lost, what we do gain in these copies are equally valuable witnesses of the treatment of late medieval printed books by their eighteenth and nineteenth-century collectors. The plate book put together by Jacob Visser gives a wonderful insight into the interest of a book collector in the changing use and re-use of woodcuts, and as such into the beginnings of the field of bibliography and book history. A fascination for images is of all times.

© Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.