Treasure hunting in databases: forgotten early medieval sculptures from Lochem

It's not so bad to work from home. Online databases contain hidden treasures of medieval art: such as these two stone carvings from Lochem.

Checking the database of the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed for my current research on medieval building inscriptions in the Netherlands, to see whether any examples had been missed, I stumbled upon the image shown below of two more or less rectangular, very high quality remnants of early medieval carvings in the Hervormde Kerk (formerly the St. Gudula Church) in Lochem, a town situated some 25 km to the southeast of Deventer.

The early medieval carvings on the two slabs in Lochem. Photographer J. van der Wal (1992), collection RCE, Amersfoort.

Where the sculpture was found

During the 1973-1975 restoration of the church, when two late Gothic panels on the exterior of the church, located left of the tower entrance, were taken out of the wall, it was discovered they had earlier carvings on their reverse. This stupendous find was first published by Harry Tummers in a 1993 article. He, incidentally, only mentions the slab with the lady on the right of the photograph and suggested a date in the tenth and possibly even the ninth century, and argued that, in view of the small measurements of the stone, it was a commemorative panel rather than a funerary slab. When still complete, it would have been slightly over a meter high. While a commemorative panel of such an early date would have been spectacular enough, I think the find is even more momentous.

The late Gothic carvings on the two slabs. Photographer J. van der Wal (1992), collection RCE, Amersfoort.

Two of the oldest medieval sculptures in the Netherlands

The fragment on the left of the first photograph shows an inscribed cross, with on top the remains of an indented medallion containing the hand of God held out in blessing. The medallion is encircled by a frame containing an inscription in classical Roman lettering. Obviously, the relief had an outer frame with an inscription also, but what remains is too fragmentary to decipher.

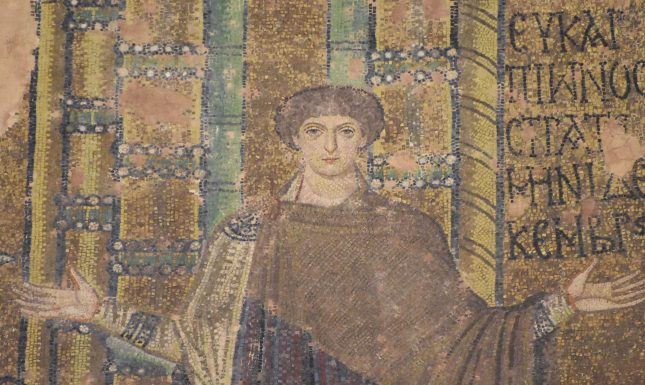

Somewhat more remains of the second panel. It shows a subtly modelled, standing, veiled lady holding her arms in a traditional early-Christian prayer or pleading posture, with the elbows close to the sides of the body and with her hands outstretched sideways, palms up. Such figures are known as ‘orans’ (male) and ‘orante’ (female) figures. The ‘orante’ posture of the lady went out of fashion after the eleventh century, when folded hands became the customary prayer posture.

The Lochem lady is wearing a long gown that leaves her feet free, with very wide sleeves, so as to reveal the long sleeves of the tunic she wears underneath. On the front, the gown has incised vertical pleats with a vertical array of beading down the middle and along the lower hem of the garment. The sleeves are likely to have been embellished with beading also, but they are too badly worn to be able to make this out. The wide rectangular frame around the lady is inscribed and, what is still there of the text, reads: …PRI. ANIM … (on the right side of the panel), A[?] … IA’ (on the bottom), and, ‘S. REQUI …’ (on the left side of the panel). The panel has therefore something to do with the soul (anima) and resting (requi…).

The lettering, style and ‘orante’-posture indicate these are very ancient carvings indeed, dating to the eleventh century at the latest. This makes them unique, as there is very little medieval sculpture from this period anywhere. In spite of their international importance, they are surprisingly unknown. The two reliefs did not even get a place in the Lochem ‘canon’ and go unmentioned in the 2000 inventory of monuments in the province of Gelderland!

The ‘orante’ posture

The ‘orante’ posture goes back to pagan times and was adopted by Jews and early Christians alike. In early-Christian art, it is seen mainly in the catacombs and on sarcophagi. The precise meaning of the ‘orans’ or ‘orante’ posture is contested. It has been held to symbolize the soul of the deceased awaiting resurrection; to represent the Christian soul in Paradise or to symbolize the blessed soul in heaven interceding on the behalf of the community or praying for those still on earth. Often, the early ‘orans’ figures are generic female types, representing deceased souls in heaven, praying for their friends on earth, which accounts for the fact that there are often female ‘orantes’ on the tombs of deceased males.

From the fourth century onwards, ‘orans’ and ‘orante’ figures were gradually individualized and came to represent specific saints and martyrs. Thus, St Agnes is shown with her arms spread upwards on a fourth-century altar antependium in Rome. In the catacombs of the Via Nomentana in Rome even the Virgin Mary raises her arms as an ‘orante’ figure. In the dome of the Hagios Georgios in Thessaloniki, martyrs named by inscriptions stand side by side raising their arms in the ‘orans’ posture. We also see St. Apollinaris holding his arms thus in the sixth-century apse mosaic of the church of St. Apollinare in Classe near Ravenna. It seems, then, that from the fourth century onwards the gesture indicated the intercessory prayers of the saints. This having been said, in other locations ‘orans’ figures could still, on occasion, represent the prayers of the faithful or the blessed in paradise, as on one of the Merovingian sarcophagi in the crypt of Jouarre.

Interpreting the sculptures

Tummers considered the stone with the standing ‘orante’ figure in Lochem to be a commemorative stone, like an epitaph. However, he seems not to have been aware of the presence of the second stone with the cross and the hand of God, which rather changes matters, as the two obviously belong together. The lady on the Lochem panel is therefore more likely to be a figure from whom to ask for intercession, a saint, praying to God or asking for his blessing, reminding him of Christ’s sacrifice, represented by the Cross. From the top of the panel, the hand extending downwards symbolizes that God’s blessing has been granted. In medieval art, the hand of God (Manus Dei), is used to indicate God’s intervention in or approval of affairs on earth. A good example of this hand of God, set in a medallion, can be found in the church of the abbey church of Gandersheim (Germany). The Gandersheim stone is thought to commemorate the consecration of the church which took place in 1007.

The presence of the Lochem female figure, shown turning slightly to the left, suggests that another figure panel stood to the left of the stone with the cross and the hand of God, with a figure turning to the right. Together these stones would have had a width of at least 147 cm, the panel with the lady being 49 cm wide. The cross and hand of God relief looks as if it may have been somewhat higher than the panel with the lady. It is thus quite possible that the two Lochem reliefs were once part of a tripartite altar retable with a kind of stepped arrangement. Although few altar retables of such an early date have survived, their former existence is attested in medieval sources from at least 1000 onwards.

Provenance?

But what are such unique sculptures doing in a place like Lochem? The very fine classical Roman lettering and the style of the sculpture suggest it came from an important workshop with high-status connections. Indeed, sculpture of such a very early date tends to come from major ecclesiastical sites and Lochem can hardly be called that. Although the origins of the Lochem church date back to the Carolingian period, at some time before 1200 the counts of Zutphen gave the church to the chapter of the church of St. Walburgis in Zutphen. This suggests it was a church of secondary importance at best. No wonder that Tummers suggested the reliefs may have come from elsewhere, the more so as it was normal practice in the Middle Ages to sell outdated church furnishings and statuary to the minor churches in the region when one was refurbishing. It is of course impossible to say whether, and, if so, when this happened. All we know is that the reliefs were in Lochem by the early fifteenth century when they were reused as part of a piece of church furnishing.

If the reliefs did indeed come from elsewhere, Zutphen is the obvious place to look to, as the Lochem church was apparently in the possession of the St. Walburgis church there. Having been destroyed by Vikings in 882, the church at Zutphen was rebuilt and dedicated to St. Peter and St. Walburga. At some stage between 1025-1050 it was given collegiate status, and was first mentioned as such in 1059. In the eleventh century, Zutphen was obviously a place of great import as a large palace was built here with a façade, 53 meters in length.

As a date in the first half of the eleventh century would to my mind perfectly suit the sculptures in question, a provenance from Zutphen does not seem at all unlikely. It may even have been a series of panels commemorating the dedication of the altar or the consecration of the church. In that case, the figures flanking the panel with the cross and the hand of God are likely to have been St. Peter and St. Walburga, the two patron saints of the Zutphen church.

So, there we are. Social isolation, awful though it may be, also has some positive side effects. Being locked up in the house gives one the opportunity to search our country’s wonderful databases and hunt out the hidden treasures that they still contain. I can thoroughly recommend it!

Literature

Harry A. Tummers, ‘Recente vondsten betreffende vroege grafsculptuur in Nederland, dertiende en veertiende eeuw’, Bulletin van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Oudheidkundige Bond 1993, 34-40.

© Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Elizabeth den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.