What has Cleopatra to do with the Crusades?

What does a picture of a dark-skinned Cleopatra do in a fourteenth-century manuscript produced at the papal court in Avignon?

About seven centuries before the Netflix series Queen Cleopatra, a manuscript illuminator from fourteenth-century Avignon decided to depict the Egyptian queen as a black woman. The result was a unique depiction of Cleopatra, showing the queen in the attire of a European noblewoman but with distinctive racialized characteristics, such as black skin, white teeth and a rounded nose (figure 1). Through a close inspection of the manuscript and its context I hope to show in this blog that the color of Cleopatra’s skin was a deliberate choice by the maker(s) of the manuscript. Their intention, however, was not to claim Cleopatra as one of their own, as twentieth- and twenty-first-century interpretations tend to do. Rather, it was to portray the Egyptian queen as ‘Other’, reflecting the crusading context of the early fourteenth century.

The manuscript: BL Egerton 1500

The image of a dark-skinned Cleopatra is found in an early fourteenth-century codex (now BL Egerton 1500), containing the so-called Abreujamen de las Estorias, an Occitan translation of the so-called Compendium or Chronologia Magna by the Franciscan friar Paolino Veneto (c. 1272-1344). The compendium takes the form of a genealogical table stretching from Creation to Veneto’s own day, and containing the lineages of the most important royal and ducal houses of the fourteenth century. It was conceived as an appendix to Veneto’s universal chronicle, which he published in 1316. After his election as bishop of Pozzuoli in 1324, Veneto reworked his universal history and its compendium into a comprehensive universal chronicle, usually called Satyrica Historia. Veneto was intimately connected to the courts of pope John XXII (r. 1316-1334) in Avignon and king Robert of Naples (r. 1309-1343), serving as member of the Apostolic Penitentiary and diplomat for the former, and as counsellor for the latter.

There are three manuscripts of the Compendium dating from Veneto’s life. The oldest one (now Venice, Marciana Lat. Z. 399 (=1610)) is likely Veneto’s autograph, written in Venice and the one from which the Abreujamen was translated. Two later versions of the Compendium were copied in Naples, one (now Paris, Bnf lat. 4939) in 1329 and one (now BAV vat. lat. 1960) during the 1330s. The Occitan translation of the Compendium was likely carried out under Veneto’s supervision at the papal court in Avignon during the early 1320s. Not only do these manuscripts testify to the importance of Veneto’s work at the papal and Neapolitan courts, they also allow us to compare the illustrations that accompany the genealogical tables of the Compendium. It is not entirely clear to what extent Veneto was involved in the decoration of the individual manuscripts: illustrators often worked from cues written in places left blank in the text. The differences between the representations of Cleopatra in each of the manuscripts, however, show that the illustrators in Venice, Avignon and Naples envisaged historical figures such as Cleopatra each in their own way.

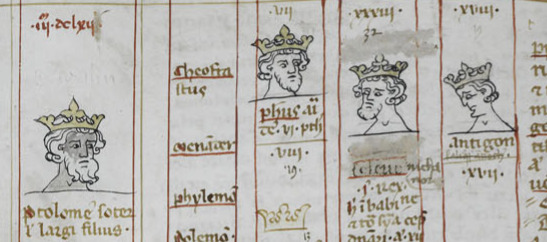

A few things stand out in the depiction of Cleopatra in the Abreujamen (figure 1) in relation to the manuscripts of the Compendium (figures 2, 3). In the Abreujamen, the illustrator made a clear effort to emphasize Cleopatra’s racial features: not only does she have dark brown skin, she also has conspicuously white teeth and a round nose. As Kim Phillips has argued, white teeth in medieval art often represent non-Christian ‘barbarous’ Others, as well as devils. The illustrator applies the same racial characteristics—white teeth, round nose—to other figures in the manuscripts. Indeed, the entire lineage of the Ptolemies is depicted as such, as are for instance the Persian kings of antiquity and the twelfth-century sultans of Damascus and Egypt such as Saladin. This is a significant departure from its model, the Marciana manuscript of the Compendium, as well as from the Naples manuscripts where those features are absent. It should be noted, however, that the figures with a racialized appearance in the Abreujamen seem to have a darker skin in the Abreujamen’s model, the Marciana manuscript of the Compendium, too—a feature that does not appear in the Naples manuscripts. Compare for instance the skin of Ptolemy I with that of the other Diadochi (fig. 4) and note that it is much darker. The same principle is applied to a much greater extent in the Abreujamen (fig. 5).

It is uncertain whether the darkening of skin in the Marciana manuscript was the original illustrator’s plan or the result of a later intervention. Yet in both manuscripts a deliberate choice seems to have been made to differentiate certain groups of people from others. What makes the Abreujamen stand out compared to the manuscripts of the Compendium are the distinctive racialized characteristics of its portraits. This begs the question: why did the Occitan illustrator make an effort to depict certain individuals as racially Other? It may come as little surprise that these individuals all come from the Middle East and North Africa. More specifically, they represent areas that were under Muslim control at the time of the composition of the manuscripts. This is no coincidence. As I shall show in the last section of this blog, the racialized portraits in the Abreujamen can be interpreted in light of efforts to organize a new crusade in the early decades of the fourteenth century.

Veneto and Crusading efforts in the early fourteenth century

After the fall of Acre to the Mamluks in 1291, popes continued their efforts to initiate a new crusade to recapture the Holy Land. These efforts were accompanied by an uptick in crusade literature in the early decades of the fourteenth century. One of these newly composed works was the Liber Secretorum Fidelium Crucis by the Venetian statesman Marino Sanudo the Elder (c. 1270-1343), a friend of Veneto’s. It presents detailed plans for a new crusade and was presented to pope John XXII in 1321 in Veneto’s home. The manuscript (now BAV vat. lat. 2972) contains several miniature drawings showing black- and brown-skinned Muslims fighting Christians in the lower margin of the page (figure 6). Moreover, the Liber Secretorum contains several maps of important cities in the Levant, such as Jerusalem and Acre, that we also find—in a very similar style—in the Compendium and the Abreujamen.

Veneto wrote his Compendium at a time and in an environment that was seeking ways to promote a new crusade. This is also reflected in the outline of the Compendium itself. Not only does it contain the aforementioned maps of important cities in the Levant, it also contains an illustrated crusade cycle stretching out from the First Crusade until the late thirteenth century. Tellingly, this is one of the only two illustrated cycles in the Compendium, the other being the life of Christ and the acts of the apostles. These cycles differ from the portraits that appear in the genealogical tables in that they depict scenes from the narrative that they accompany. Although disguised as a world chronicle, Veneto’s Compendium seems to have had a clear goal of highlighting the Crusades as the most important events in the history of the world after the incarnation of Christ.

How does this relate to the black-skinned Cleopatra in the Abreujamen? As can be seen from the illustrations in the Liber Secretorum, it was not uncommon that Muslims were depicted with dark skin in the early fourteenth century. This was part of a wider historical phenomenon: black skin, or blackness in general, was seen as a marker of sin, and was used to signify enemies of Christendom. The racialized depictions of Muslim leaders such as Saladin in the Abreujamen should be interpreted in this light as well: in the eyes of a person like Veneto, the Muslim leaders in the Middle East were the embodiment of sin. The fact that individuals from pre-Islamic (and pre-Christian) times were depicted in a similar manner suggests a similarity, if not continuity, between Christianity’s foes during the Crusades and the ancient kings of Persia and Egypt, the archetypical Old Testament enemies of Israel. Obviously, Cleopatra had little to do with either the Old Testament Jews or the early Christians, but her status as queen of Egypt seems to have been enough to justify the artist’s depiction of her.

Conclusion

Skin color matters. It did in 1320; it does now. It is the meaning attached to it that has changed and it is the task of the historian to distill that meaning. Ultimately, the many reimaginations of Cleopatra tell us more about the time in which they were produced than they do about the historical Cleopatra. Still, Cleopatra’s portrait in the Abreujamen is one of the very few examples in history where the artist does not depict her as a white woman. It is also one of the earliest known postclassical depictions of her. While this does not suggest any open-mindedness on the part of the artist (rather the opposite), it does show that she has not always—for reasons better or worse—been imagined as a white woman.

Further Reading

Federico Botana, “The Making of L’Abreujamen de las estorias (Egerton MS. 1500)”, eBritish Library Journal 2013, article 16.

Geraldine Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge, 2018.

Kim M. Phillips, “The grins of others: Figuring ethnic difference in medieval facial expressions”, postmedieval 8:1 (2017), 83-101.

Manuscripts cited

London, British Library, Egerton 1500 (unfortunately offline since a cyber-attack in November 2023)

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, lat. 4939

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, vat. lat. 1960

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, vat. lat. 2972