Daily life in the medieval town hall

Historians have often refrained from looking behind the front door and façades of yet well-known medieval monuments: town halls. What was going on inside these public buildings?

Much of medieval city life is known through sources such as ordinances, statutes, law codes, chronicles, and cases brought to local courts. Town halls, however, are relatively infrequently or at least not consistently mentioned in such writings. It is therefore not easy to step into these still prominent buildings. But sometimes a specific type of sources suddenly surprises and opens up worlds, in this case city accounts. These accounts are of course useful to study the town hall’s construction, but also contain other enriching details which shed light on daily life inside such buildings. For many medieval scholars perhaps not the most attractive source material, the accounts helped me to further explore the uses of town halls as public buildings in my recently defended PhD research. In this blog I will share some of my finds from the Aalst (BE) and Leiden city accounts. I will use them as starting points to further explore how governments tried to keep town halls undisturbed places, which was far from self-evident.

Double walls preventing eavesdropping

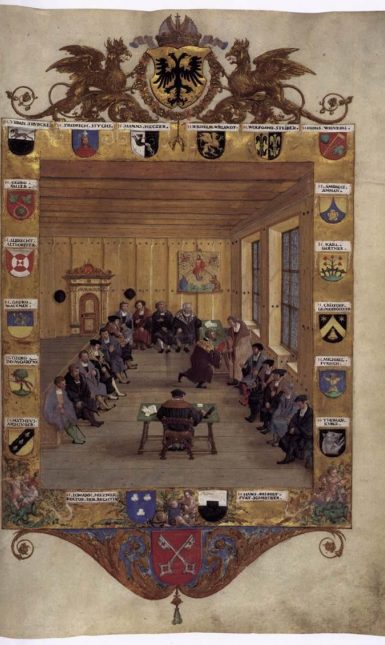

Town halls were highly public buildings as well as places used for seclusion. In 1451 the city accounts of Aalst include a reference to a seemingly new addition to the town hall (the oldest in the Low Countries): a deliberation room, constructed by means of wooden walls with a door. The aldermen used this room for instance during public trial, in order to have a place for enclosed and confident discussions. Apparently the space still was not (or no longer was) sufficient for this use in 1456. In that year the accounts capture the activities of the carpenter Rubbine de Pleckere, who had built a double wooden wall ‘so one could not hear the arguments of the aldermen’.

Apparently the deliberation room was not soundproof by 1456, urging the aldermen to order two wooden walls as to facilitate more protection. The explanation in the city account suggests this was necessary; people could possibly hear aldermen talking outside their chambers. And this was indeed likely. The magistrates’ chambers were located at the upper level of the building, which also contained the public courtroom (vierschaar). Thus on days of public hearings, for instance, legal parties and an audience were present in close proximity to the magistrates’ secluded deliberations. Although unknown for late medieval Aalst, there are examples of prosecuted eavesdropping incidents in town halls of other cities. For example in Leiden, where a certain Pieter Ysbrantsz was caught by a guard when he stood outside the council chamber, listening to ‘what one did in the chamber’.

The expenses on wooden walls as recorded in the Aalst city accounts of 1456 thus show a glimpse of the town halls functioning: as a place for meetings beyond sight and earshot, as well as more public spaces, both with people eager to acquire information close by.

Acting against damage and noise

In the hustle and bustle of a city there is of course always (un)predictable or rebellious disturbing behaviour. This was no different in and around the town hall. In 1457 Aalst, the city made expenses on new windows because children had been throwing rocks. Perhaps the Leiden magistrates needed a good excuse in 1463 to explain why they needed to replace green wall hangings several years in a row. In any case the city accounts justified the costs by blaming dogs that had been tearing the cloth. There are other examples, such as in Gouda, were authorities acted against people – including children – who played ball games inside the town hall.

Although city accounts often only provide some evidence for single cases, they also show the presence of many daily disturbances. This is where the accounts inform about access and movement of various urban inhabitants beyond the more fervid cases that made it to the criminal court. And why wouldn’t there be children and dogs inside the buildings, as long as they wouldn’t interrupt officials during their working activities? Indeed, magistrates regulated certain disturbances especially during court proceedings. For example, in Gouda the aldermen stated in 1488 that talking was not allowed in the town hall whenever the court was in session. What is more, in many criminal records we encounter people the magistrates penalised for what they considered verbal and physical attacks, especially during official meetings. And this is the other side of the story: for many urban dwellers the town hall was a place to show their discontent through various forms of utterances.

Cleaning to get rid of corruption

In 1486, the Aalst magistrates – or ‘the good man of the law’, as the city accounts mention – returned to the city after the height of plague infection and increased mortality had come to an end. They paid a man called Willeme den Nokere to clean and ventilate the city’s town hall, both upstairs and downstairs, in order to repulse ‘all corruption’.

This is at least the explanation in the city accounts of that same year. The situation illustrates sort of a late medieval ‘going back to normal’ after a pandemic, when people return to their offices, though still with caution. More specifically, however, the account underlines the connection between bad air and corruption, which is why the windows needed to be opened and the building to be cleaned. Indeed, contemporaries considered bad air an important transmitter of disease, but also as a polluting source that might endanger the clarity of thoughts, morality, and politics. Corrupted air thus needed to be prevented, as was the case with other forms of uncleanliness. In Leiden, magistrates decided a kitchen in the town hall to be removed as the cookery was corrupting the public courtroom.

Expenses on cleaning such as the one described above occur often in city accounts of different cities. It seems that people disposed of dirt, swept the corridors, and kept (parts of) town hall spaces clean all year around. Perhaps one can imagine that these buildings – being frequently visited – were vulnerable for dirt anyhow. As mentioned above, dogs and children entered town halls as well. There are strong indications that municipalities, next to paying cleaners, tried to prevent all sorts of uncleanliness. For example, the famous Het Rechtsboek van Den Briel (1444) stated that it was not allowed to cause ‘uncleanliness in the town hall’ and that those who brought ‘trash’ in the surroundings of the building should remove it. Authorities were not occasionally but ongoingly preoccupied with keeping town halls clean, in order to maintain the proper functioning of activities in such buildings.

The town hall as a public building

The city accounts of Aalst and Leiden provide us with a glimpse of daily activity inside the town halls, indicating at least what authorities paid for in this regard. Much of this is not included in this blog. For example, administrative activities formed a large part of town hall use. But the discussed details in the expenses resemble the larger image as derived from statutes, legal treatises, and records from criminal courts and civil disputes: the town hall was a place where different people encountered and contested each other. It was a place of access as well as seclusion, of noise as well as quietness. These aspects had their advantages and disadvantages, especially (but not exclusively) for the authorities that desired to keep the building and its functions as organised as possible.

Sources:

Algemeen Rijksarchief Brussel (ARA), archief rekenkamers, reeks stadsrekeningen van Aalst 1395-1786, reg. 31480, f.27v; 31450, f.56r; Erfgoed Leiden en Omstreken: Stadsarchief Leiden (SAL), correctieboek A, f.203r; ARA, reg. 31451, f.31r; SAL, inv. no. 530, f.155v; 532, f.17r; ARA, reg. 31480, f.27v; SAL, inv. no. 0508, 381, Vroedschapsboek 1449-1458, f.19r. J. Fruin and M. Pols (eds.), Het rechtsboek van Den Briel, beschreven in vijf tractaten door Jan Matthijsen (The Hague 1901) 182.

The examples and late medieval town halls are further discussed in:

Nathan van Kleij, Beyond the Façade: Town Halls, Publicity, and Urban Society in the Fifteenth-Century Low Countries (PhD-thesis, University of Amsterdam 2021).

© Nathan van Kleij and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Nathan van Kleij and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.