Where is Gogo? Friendship and poetry at the Austrasian court

In a poem, Venantius Fortunatus wonders where his friend Gogo could be. The answers reveal the activities and friends of an Austrasian magnate in sixth-century northern Gaul.

I have been mapping the activity of Merovingian elites as described by historical sources. One poem in particular, written by Venantius Fortunatus to his friend Gogo, piqued my interest. The poem describes the various places in northern Gaul where a member of the Austrasian royal court in the later sixth century might find themselves. But the poem also highlights the activities, cultural pretensions and friendships that mattered to the elite of Merovingian Gaul.

A royal wedding

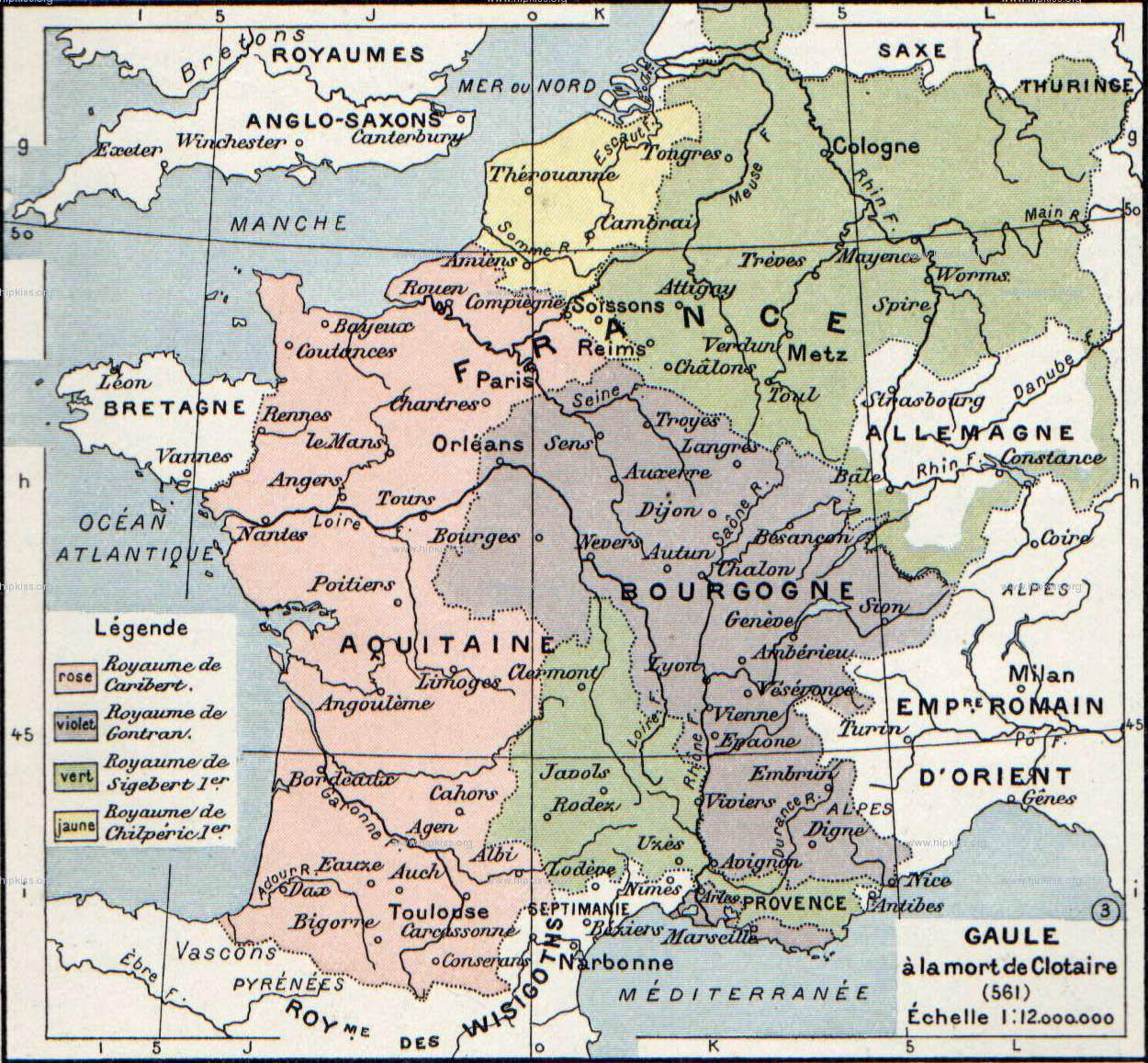

This story of courtly life and friendship starts, fittingly, with a royal wedding. In the year 566, the young poet Fortunatus left his native Italy to travel to northern Gaul. Either by chance or invitation, he ended up at the Austrasian court (possibly in Metz), to attend the royal wedding between King Sigibert (r. 561-575) and the Visigothic princess Brunhild. While there, Fortunatus had the opportunity to recite his poetry in honour of the royal couple, visit Austrasian towns (such as Cologne) and befriend local notables. One of the friends he made was an important royal official called Gogo.

Gogo is not a famous person in Merovingian history. The main source for the period, Gregory of Tours’ Histories, mentions him only once in passing (when he dies in 581). From Fortunatus, we learn that Gogo was one of the foremost members of the Austrasian court. He was responsible for escorting princess Brunhild from Toledo, Spain, to northern Gaul. He also served in the office of comes or ‘count’ (in this period, still a temporary function as provincial administrator or palace official).

After king Sigibert’s death, Gogo climbed up even higher and became nutricius, some kind of guardian or teacher to Sigibert’s son and infant-king Childebert II. Not for nothing, Fortunatus concluded, ‘You are considered great in the judgement of the prince [=king], Sigibert’ (7.1.35, transl. George).

In this blog, I will focus on poem 7.4. The translation used throughout is from Roberts 2009: 258.

Writing letters

In the poem, Fortunatus asks the clouds where his friend Gogo could be and inquires after his friend’s wellbeing.

“Clouds who come on the blast of the fierce north wind,

who, suspended on high, move with the sun in the starry heavens,

tell me what health my dear Gogo enjoys.

What occupies his carefree mind in tranquil times?” (l. 1-4)

It is easy to be distracted by the poem’s florid literary style. Letter writing in the Early Middle Ages was an important way to stay in touch with friends and loved ones, sustaining bonds of amicitia or friendship. Whereas we might send an e-mail or a message on social media asking a simple ‘how are you’, Fortunatus writes most of his letters (which are preserved) in an embellished style of literary Late Antique Latin. In doing so, he stood in a long-running classical tradition of aristocratic letter writing, from Pliny the Younger (61-113) to Sidonius Apollinaris (430-489).

This should warn the modern reader immediately: we should not take the poem too literally. Maybe Fortunatus truly did not know the whereabouts of his friend, but that is beside the point. Asking this question provided the poet with the opportunity to praise Gogo and honour their friendship.

Mapping Gogo

The clouds do not respond to the poet’s question. Instead, the poet sums up a list of possible answers, starting with several major rivers in northern Gaul.

“What occupies his carefree mind in tranquil times?

if he lingers by the banks of the wave-driven Rhine

to catch with his net in its waters the fat salmon,

or roams by the grape-laden Moselle’s stream,

where the gentle breeze tempers the blazing sun,

where vine and river moderate the midday heat:

shade under the knitted tendrils, water with fresh flowing waves.

Does the Meuse, sweetly sounding, haunt of crane, goose, gander, and swan,

rich in its threefold wares, in fish, fowl, and shipping,

hold him, or where the Aisne breaks on grassy banks

and feeds pastures, meadows, and fields with its waters?” (l. 5-14)

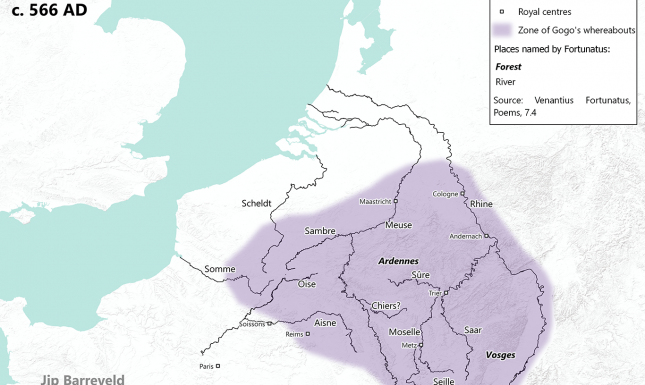

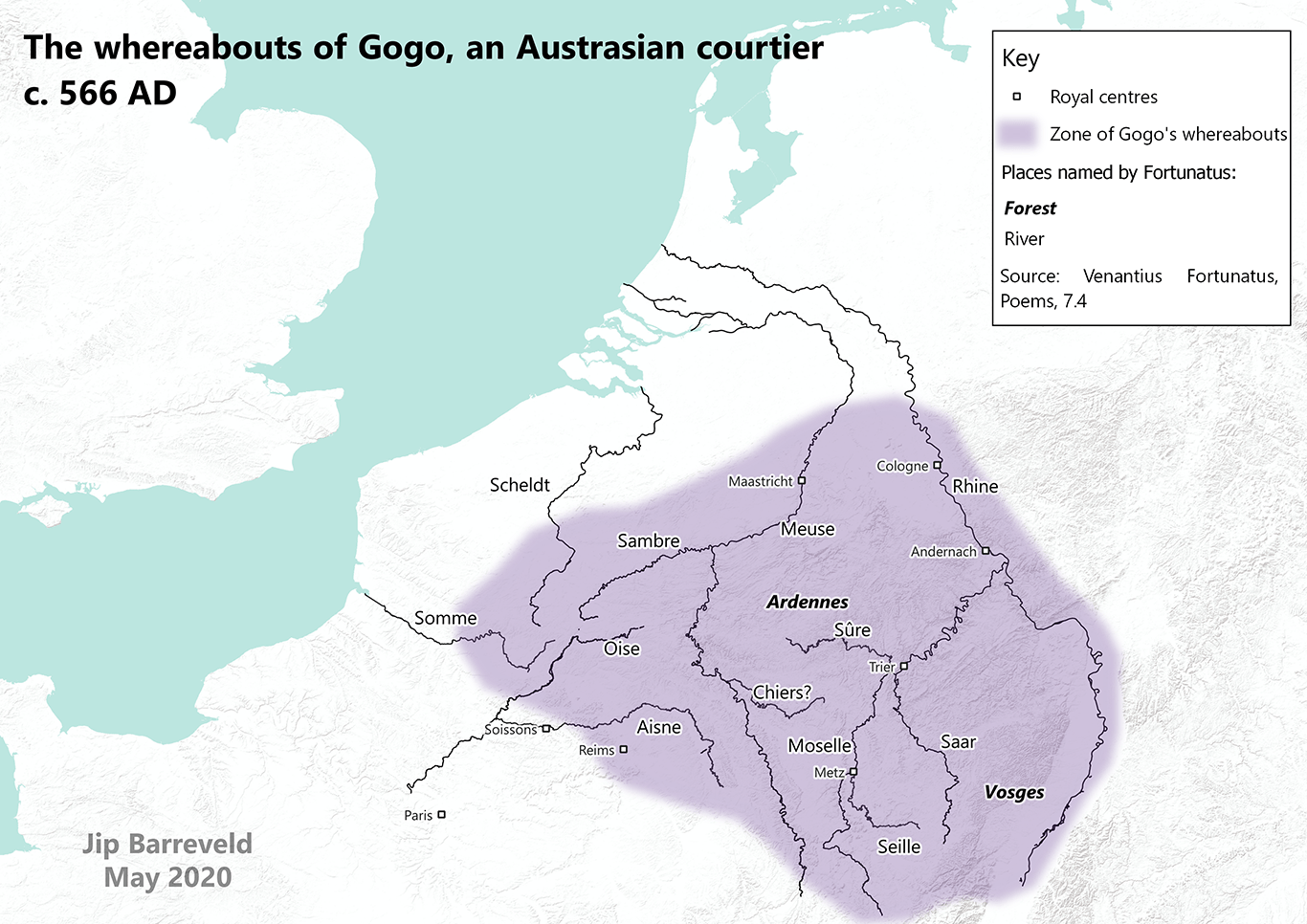

After these four rivers, Fortunatus also briefly mentions the rivers Oise, Saar, Cheir (or Chier), Escaut, Sambre, Somme, Sauer and the Seille. Finally, he mentions two forests: the Ardennes and the Vosges (l. 15-19).

Since Gogo’s whereabouts might also reveal those of the Austrasian court more generally (Early Medieval kings may have travelled around their kingdoms with their court), I decided to map all the rivers and forests mentioned in the poem. Because the resulting area is rather large, I then mapped a smaller zone of “Gogo’s whereabouts”, which includes all the rivers, forests and important Austrasian royal centres in the smallest possible area (more or less).

Going back to the poem, there is one problem though. It is clear that Fortunatus’ description of the rivers is highly schematic and idealized. Rivers are a recurring element in Fortunatus’ poems, and he draws extensively on Roman literary examples when doing so, especially Ausonius’ fourth-century poem on the Moselle river. Rather than providing accurate, sixth-century geography to the modern historian, the poem is more interested in picturing a nostalgic landscape that evokes the world of the fourth-century Gallo-Roman landowner.

Associations between river and primary production | ||

|---|---|---|

River | Association | Activity |

Rhine | salmon | fishing |

| Moselle | vineyards | farming |

| Meuse | waterfowl | hunting |

| Aisne | meadows & pastures | pastoralism |

A "Roman" gentleman

The first half of the poem enumerates the various rivers, the second half mentions the various activities Gogo might be engaged in. The first one is hunting in the woods.

“Or else does he wander the sunny groves and glens

and with his net snare wild animals, with his spear kill them?

Does the forest crack and thunder in the Ardennes or Vosges

with the death of stag, goat, elk, or aurochs, shot by his arrows?

Does he strike between the horns the brow of the sturdy bison,

can bear, wild ass, and boar no more delay their fate?” (l. 17-22)

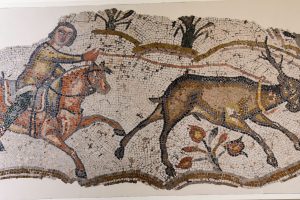

The next location Gogo might be at is his estate, tilling the soil (l. 23-24). The text does not give a location, but we do know from elsewhere that Gogo owned property near Metz. The poem is more interested in representing Gogo as a Roman gentleman landowner. Hunting is a popular motive in Late Antique villa mosaics and was a favoured past-time of Roman aristocrats. Compare, for example, the above passage with Pliny’s Epistle 1.6. Here, Pliny, while on the hunt with his slaves and retainers, enjoys the peace of the forest to do some writing.

Gogo, too, had a penchant for literature, which the poem references next:

“Does he now sit joyfully in the palace hall

with an attendant retinue that rejoices in their love for him?” (l. 25-26)

The translation ‘attendant retinue’ conjures up the image of a Frankish lord with his warrior retinue. But the Latin schola in its classical sense refers to a school, or disciples of literature. The ambiguity was probably on purpose, depicting Gogo both as a Frankish leader and educated Roman gentleman. In another poem, Fortunatus compares Gogo’s eloquence to Orpheus and his lyre (7.1). Four letters written by Gogo himself are preserved, where we meet him as a capable writer in charge of royal correspondence.

Gogo's friends

The final possibility suggested by the poem for Gogo’s whereabouts is outside of court, involved in regional administration.

“Or does he join with my dear Lupus to dispense merciful justice,

to create by their common counsel a soothing honey,

by which the poor are fed, widows gain comfort,

the young receive a guardian, and the needy aid?” (l. 27-30)

Here, Gogo is emphasised for his good Christian virtues (feeding the poor, protecting the weak). This reinforces the Christian elements within the poem as a whole, for example in the presentation of the Austrasian rivers as an Edenic paradise.

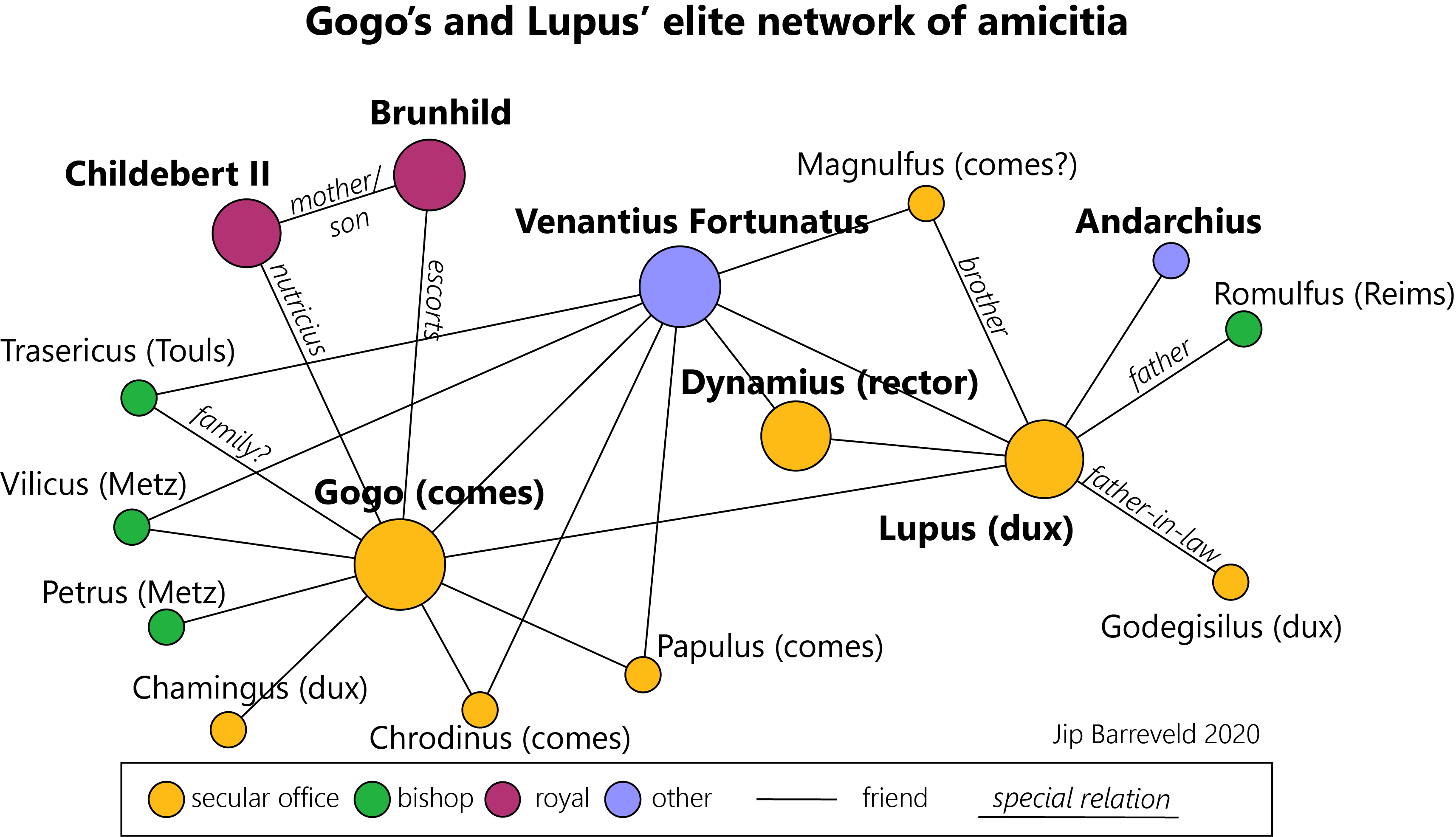

Gogo’s friend Lupus is an important Austrasian dux (or duke) from Reims, and also a "pen-pal" of Fortunatus. Lupus had literary interests himself: he offered patronage to the slave Andarchius from Marseille, who was an expert in Virgil and Roman law. Lupus and Fortunatus, probably Gogo too, were also friends with Dynamius, the governor of the Provence, who was part of a Provençal literary circle.

These men were steeped in classical Latin literature. Their literary correspondence was the basis for their bond of amicitia, and together they formed a powerful network of magnates advancing their ambitions at court. The majority of this correspondence is, sadly, only preserved in Fortunatus’ poems.

Still, we should be glad that many of Fortunatus’ poems have survived until today. While Merovingian history is filled with stories of war and violence, Fortunatus’ poetry reveals a picture of courtly life that is very different from the stereotype of bloodthirsty barbarian warlords. Men such as Gogo would have preferred to see themselves portrayed as Roman landowners, Christian administrators and poets lingering in the gentle breeze of the Moselle valley.

Translations

There is unfortunately no comprehensive translation of Fortunatus’ poems in English. Partial translations are:

Joseph Pucci, Poems to Friends: Venantius Fortunatus. Translated, with Introduction and Commentary (Indianapolis 2010).

Judith George, Venantius Fortunatus: Personal and Political Poems. Translated with Notes and Introduction, Translated Texts for Historians Volume 23 (Liverpool 1995).

Literature

Michael Roberts, The Humblest Sparrow: The Poetry of Venantius Fortunatus (Michigan 2009).

© Jip Barreveld and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jip Barreveld and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.