Who’s That Guy? Identity Crisis in a Fifteenth-century Woodcut

In fifteenth-century illustrated printed books printers regularly re-used their illustrations. When working with this material, a feeling of déjà-vu is not uncommon. But sometimes you recognize just one person, and you ask yourself: Who’s that guy?

When leafing through fifteenth-century illustrated printed books, it is not uncommon to experience the feeling of a déjà vu. Printers frequently re-used their illustrations for various reasons, mainly economic. Having woodcuts designed and cut was a relatively large investment and woodblocks could last for decades if not centuries. It therefore does not come as a surprise that the same image is used in various books, as an illustration to different texts. This may seem odd, but it is of course not unlike the current use of stock photography. Sometimes, however, the feeling of a déjà vu can be slightly different: it is not the entire image that you recognize, but just one person. This is where it gets (even more) interesting.

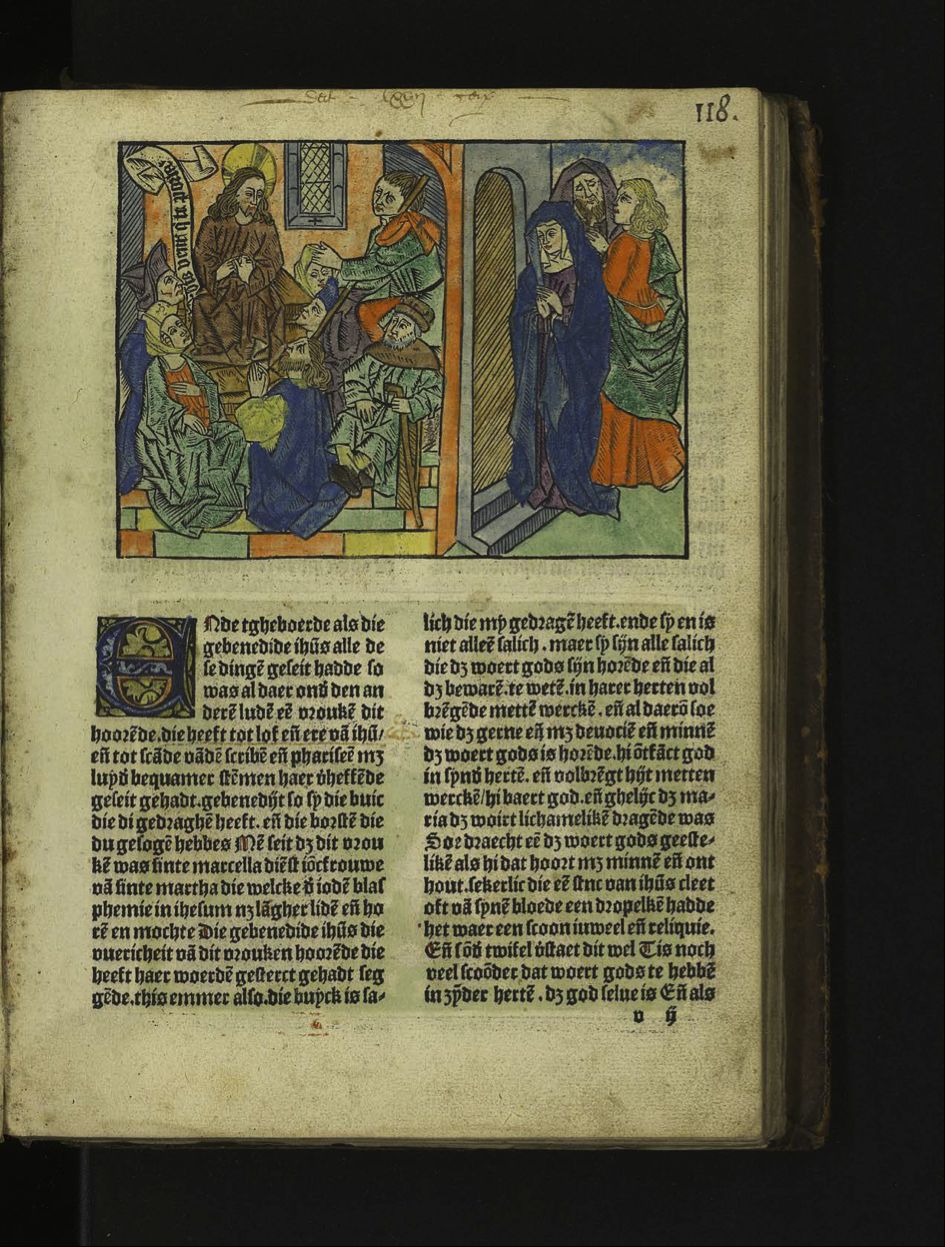

Figure 1: Book on the Life of Christ, Antwerp: Gerard Leeu, 1487. Liège, University Library, XV.C164, fol. v2r.

Hmm, I have seen him before…

While studying one of the most beautiful printed books produced in the fifteenth-century Low Countries, the so-called Book on the Life of Christ (Boeck vanden leven Ihesu Christi), I stumbled upon a woodcut that caught my special attention (figure 1). The book contains a richly illustrated account of the history of salvation, told by the allegorical figure of Lady Scripture to Man in the form of a dialogue. Gerard Leeu († 1492), one of the most prolific publishers of the fifteenth-century Low Countries, published the earliest known edition in Antwerp in 1487.

In itself, the woodcut may not seem that special. The image is spatially divided by an architectural construction: on the left (inside) we see Christ preaching, while on the right three persons are waiting outside, at the door. The latter are Mary accompanied by Christ’s brothers, who, according to the text, were looking for Christ. The preaching scene on the left portrays an episode described in the Gospel of Luke and recounted by Lady Scripture in chapter 72 of the Book on the Life of Christ. While Christ is preaching, a woman in the crowd raises her voice in support of Christ. She proclaims the following words: Beatus venter, qui te portavit, et ubera quae suxisti (‘Blessed is the womb that bore You, and blessed are the breasts that nursed You’, Luke 11:27). These words are partially visible in the banderol that escapes the mouth of the woman on the front left. She is thus the woman speaking to Christ. Christ, in turn, does not look at her. His gaze seems focused on an elderly man in the right corner.

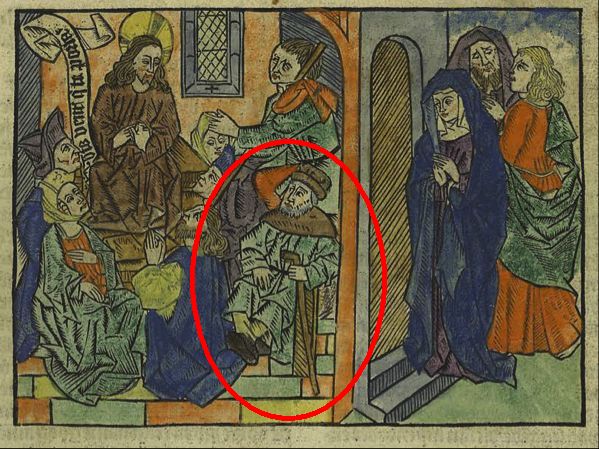

To illustrate the Book, Gerard Leeu re-used woodcuts from earlier editions. But he also had new woodcuts made specifically for this edition, among them the one illustrating chapter 72. It is one of the woodcuts that were made specifically for this text – and it does indeed fit very closely with the narrative. And yet, it was this image that triggered a feeling of déjà vu: not because I had leafed through the book before, or because I recognized the image as a whole, but because one of the persons in the crowd listening to Jesus looked suspiciously familiar. I was sure I had seen the guy in the front right position – the very man that Christ looks at – before (figure 2).

Figure 2: Woodcut, hand coloured. Book on the Life of Christ, Antwerp: Gerard Leeu, 1487. Liège, University Library, XV.C164, fol. v2r.

It is Joseph! But is it?

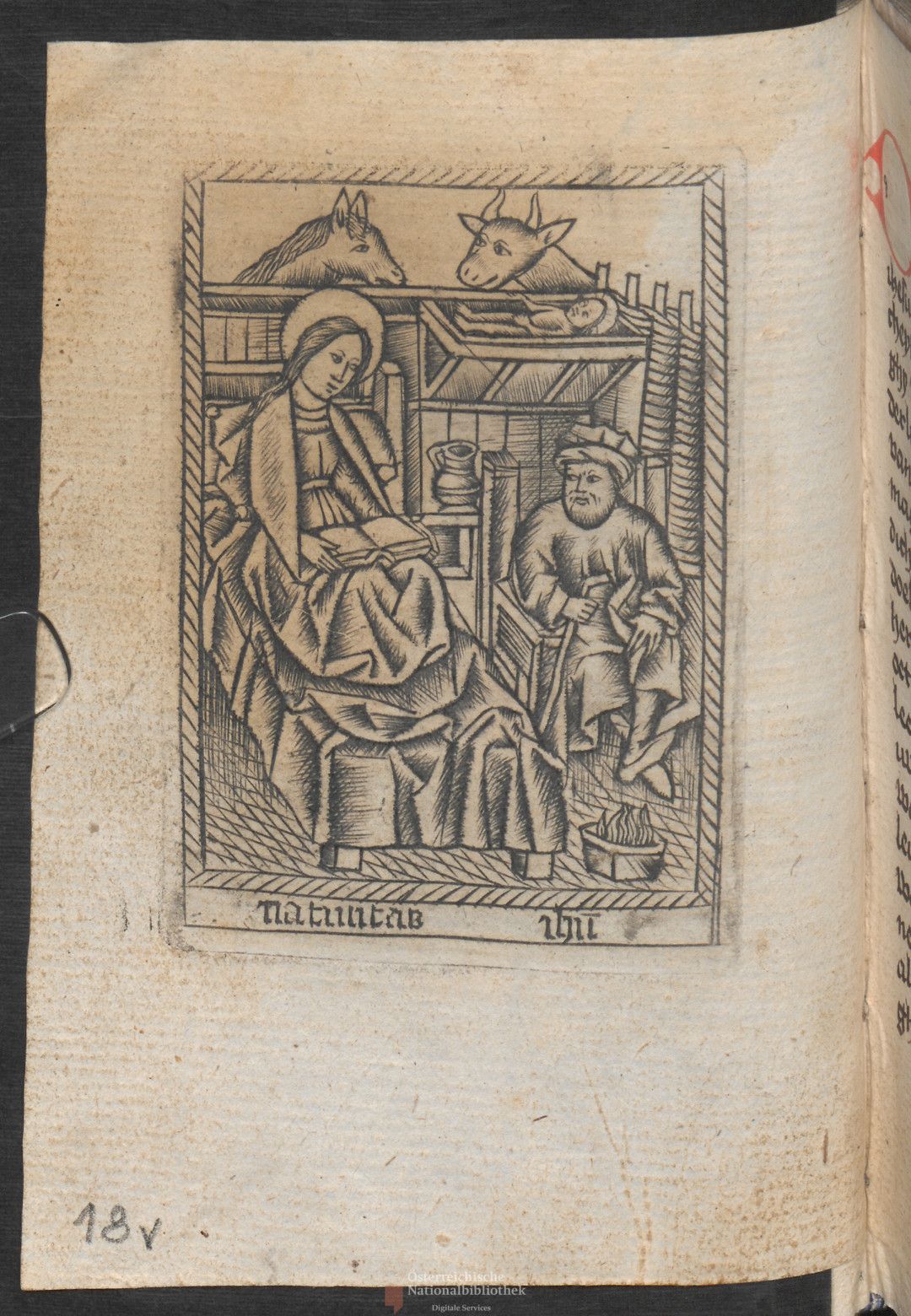

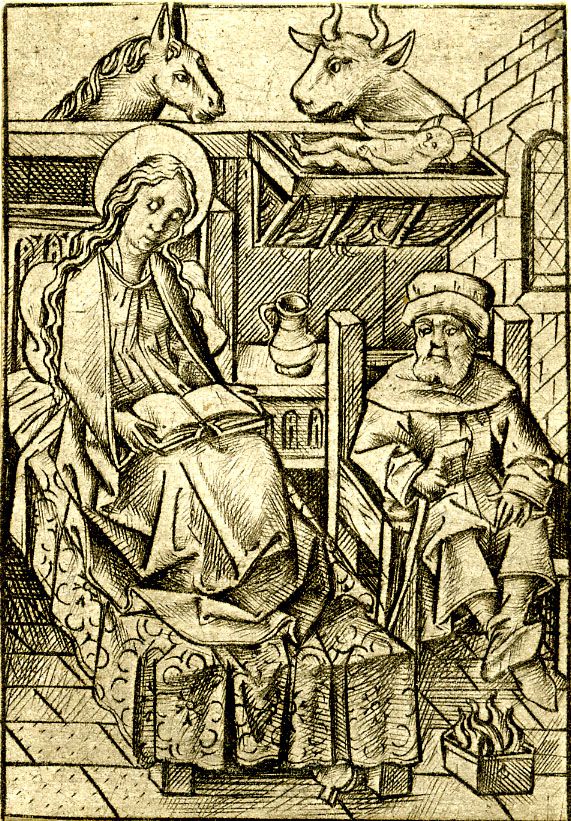

As I scoured my memory, I soon realised that this was the man who can usually be found sitting next to Mary in a frequently used composition – with slight variations – of the Nativity scene. We find this composition in various Biblia pauperum block books, for example, in an engraving by the so-called Master of the Ten Thousand Martyrs (figure 3) and in one by Israhel van Meckenem (figure 4), but also in an illustration cycle made for the Haarlem printer Jacob Bellaert (figure 5). Mary, who has just given birth, is lying on a bed and reading a book, while Joseph relaxes in an armchair and warms his feet at something that seems to be a medieval version of one of those disposable barbecues available in summer at your local supermarket. They have put the naked Christ Child out of their sight, in a somewhat dangerous looking hanging crib, left to the watchful eyes of the easel and ox. There are some remarkable similarities between Joseph and the man present at Christ’s sermon: notice the position of their feet, their cane, and the resemblances between their dress, headgear and facial hair. The head of the man in the crowd listening to the sermon is slightly more tilted upwards, however. That is why he looks at Christ directly – and Christ at him.

So the man in the woodcut used by Leeu to illustrate the events described in chapter 72 of the Book on the Life of Christ (Luke 11:27) is Joseph. But what is Joseph doing in a crowd listening to Jesus preaching?

Figure 3: Master of the Ten Thousand Martyrs, prayer book, Dutch, after ca. 1485. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Ms. Series Nova 12909, fols. 17v-18r.

Figure 4: Israhel van Meckenem, ca. 1460–1500, engraving, paper, 69 x 48mm, London, British Museum, inv. 1850,0223.6 (artwork in the public domain; photo: © Trustees of the British Museum).

Figure 5: The Nativity from Devote ghetiden vanden leven ende passie Jhesu Christi. Haarlem: Jacob Bellaert, 1486. Special Collections, University of Amsterdam, Inc. 421, fols. e4v-e5r.

Possible Scenarios

Even though this is a woodcut that was not re-used, it still confronts us with a form of re-use and compilation. This is recycling on a different level, however. A pre-existing figure is borrowed for a new composition. But why? Joseph is not mentioned in the text and his presence seems rather odd. It might be the case that the designer of the woodcut was simply looking for a seated person to complete his composition and used Joseph from one of the earlier Nativity compositions as a template. Maybe his creativity let him down that day, or was it simply laziness or even haste (but then why would he not quickly draw something of the top of his head)? Numerous other speculations could be put forward here. The only thing we can be certain about, is that the image of Joseph, and thus of one of the Nativity compositions, was available to the person(s) who made the woodblock for Gerard Leeu.

The use of templates has been attested in early Netherlandish painting (where sometimes pouncing dots and tracing lines are visible) and it is not unthinkable that something similar happened here. Book historian Lotte Hellinga has pointed to similarities between single figures in manuscript illumination and woodcuts. The insertion of Joseph into the crowd present at Christ’s sermon – turning him into an anonymous spectator – also fits in well with the broader medieval culture of compilation, adaptation and recycling, applied equally to texts and images.

The inclusion of Joseph, however, might have been done with a deeper meaning in mind. As the Nativity composition was relatively widespread, the maker of the woodcut might have included Jospeh in the hope that reader-viewers would recognize the figure as Joseph, and that they would call back in their minds the Nativity composition. There, Joseph does not look at Christ, but at Mary’s book: he looks at the Word lying on the blessed womb that bore Christ, and as such at the womb the woman in Luke 11:27 refers to. We find her words spelled out in the banderol in the woodcut that accompanies chapter 72 of the Book on the Life of Christ. Here, Joseph looks at the preaching Christ, and thus at the words he is uttering. The maker of the woodcut might have wanted to establish a closer link between the image and the main lesson exposed in the text of chapter 72 by including a figure who was actually present at Christ’s birth. As the text tells the reader: ‘...who hears the word of God delightedly and with devotion and love, he receives God in his heart and when he practices it [the word] with his works, he bears God, and in the same way as Mary was bearing the Word bodily, so he [the attentive listener] bears the Word spiritually’. In the composition of the woodcut Joseph could function as a Assistenzfigur who directs the eye of the beholder to Christ, and thus to the Word. If the viewer knew the Nativity composition from which Joseph was taken, he might distinguish deeper layers of meaning. With regard to medieval woodcuts, the answer to a simple question such as ‘Who is that guy?’ may thus not be as straightforward as it might seem.

© Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.