Women in Late Antique Bactrian Documents

How did late antique Iranian societies receive “women”? What kind of “rights” did women have in those societies?

How did late antique Iranian societies receive “women”? What kind of “rights” did women have in those societies? The answer we usually hear is: 'we do not know much about it because the male-dominant societies in late antiquity represented women often as “a man’s property” and did not leave space for women to represent themselves'. However, this statement does not apply to late antique Iranian societies, whose diversity in languages, religions and cultures has been largely neglected. In this short note I will discuss some Bactrian documents found in present-day northern Afghanistan (corresponding roughly to late antique Bactria) to see how women were represented in late antique Bactrian society. The Bactrian documents are written in the Greek alphabet and are dated between the early 4th and the late 8th centuries.

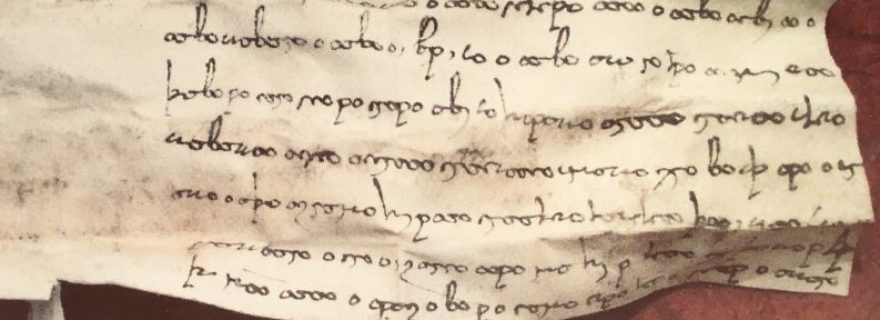

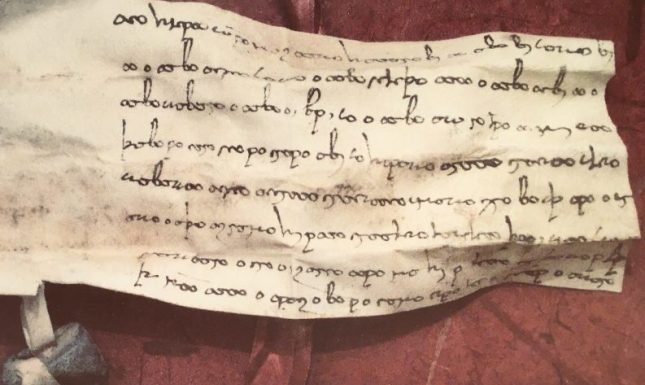

A marriage contract between a woman and two brothers

In Bactrian society, people were recognised either as freeborn or slave. These social labels defined the social rights of a person. A woman’s rights depended on her social status. Generally, women formed the foundation of the Bactrian family. Her situation changed once she married. She acquired certain rights that she did not have in her bachelor period. A Bactrian marriage contract produced in the year 110 of the Bactrian calendars (corresponding to 332 CE) in Rob region in southern Bactria illustrates the rights of a married woman. According to this document, two brothers named Bab and Piduk married a woman named Ralik at the same time. In other words, Ralik entered a fraternal polyandry in which a woman married more than one man. The document mentions that this type of marriage was “the established custom” in the region. From Chinese and Arabic sources, we know that fraternal polyandry widely practiced in eastern Bactria and continued during the Islamic period. Pulling capital into the household and religious beliefs could have justified this type of marriage.

This marriage contract reflects the transition from being a bachelor to a married woman. Ralik is called “zin” (ζινο) meaning “woman” when she was asked for marriage by the grooms’ father. Once she married, she was called an “ol” (ολο) or a married woman. The grooms’ father promised that he would treat her like an “asnuh” (ασνωυο) meaning “fully privileged daughter-in-law” in his house. The grooms also declared that they received Ralik as their “wife” in their home. She was then recognised as “finz farmanz” (φινζο φρομανζο) or the “lady” who possessed authority in the house.

The marriage contract includes an important section that guarantees Ralik’s rights after her marriage. It mentions that the grooms had no right to take another wife, or to keep a freewoman as their “concubine” without Ralik’s agreement. If they did, then they were to pay a fine to her and to the government. If a son was born from Ralik, then she could decide for him to stay at home, or to work for others. However, if a girl (“logd”. λογδο) was born from her, then not she, but the family decided for the girl. The document mentions that the employers of the grooms had no right to impose duties on Ralik or claim her children to be their slaves. If they did, then they should pay fines to Ralik's family (her new family) and to the government. She also received a dowry for her marriage. Some other legal documents mention that farming land could have been given as a dowry too.

Women in legal documents

Married women were always mentioned alongside their husbands in Bactrian documents. For example, she could join her husband and witness a legal deal. A loan document shows that a woman named Wiraz-finz accompanied her husband Deb to a market to receive 40 silver dirhams. Her name is mentioned after her husband’s name in the contract and in the place of the witnesses. However, most Bactrian legal documents do not include women’s names, showing that women were not always present in each and every legal deal, but the Bactrian legal system did not totally exclude them. An Arabic document produced in ca. 766 in Rob region mentions that a woman named Hamra appointed a man to receive her dowry. That looks like she appointed an ‘advocate’ to follow her case at the court of law.

In time of difficulties, women expected to be protected by their families. If the family was attacked, then that family expected the authorities to protect them. A letter possibly written in ca. 350 in Rob indicates that the lady of the house of Absigan lived in the in inner quarter of the house was disrespected by a government’s agent. Her complaint and appeal for protection reached the local authorities through the weaver of the damask who possibly worked at her house. Another letter issued in ca. 485-517 in Rob mentions that some people complained against a certain Ohrmuzd who bothered them and molested their women. The local authority warned Ohrmuzd that he would be arrested if he continued his mischief. In a contract of undertaking signed between two families to end a quarrel, protection of women and children are prioritized. In this document “wife and children” are mentioned amongst other properties. Whether women and children counted as a man’s property is not fully clear in this document. However, the female slave and the concubine were counted as properties. A female slave could have been sold, gifted, or punished for her misdeeds. Possibly, the same was with her children. In the Bactrian legal system, slaves could become free people only if they paid their price, or performed good service that satisfied their owners.

Women of elite families

Women from the elite families were treated differently. In the documents, they were often called “bano” (βανο) meaning the queen, or the lady of the house. The portraits of elite women were often made very majestic on seals, showing their lavish ornaments. They had servants, properties like farming land, and lived in better places. A letter produced possibly in ca. 350 in Rob region shows that the princess Dukht-anosh had authority to judge her own servants and punish them. However, her authority did not go beyond that and she could not punish the servants of the commander the fortress who functioned like today’s chief of the city police. Another letter issued in 700 CE, by the Turkic queen of Kadagstan in eastern Bactria mentions that the queen had a child who was ill and dying, but God Kamird performed miracle through his priest Kamird-far, and as result, her child was healed. In return, the queen honoured the priest by giving him farming land and a slave-girl. This shows that a female slave counted as property of a freeborn woman, and the latter could gift the female slave to a man as mark of honour.

Conclusion

The above-mentioned documents are just a few examples of representations of women in late antique Bactrian society. They show that there was not one fixed way to treat the women. They were received differently based on their social status and family backgrounds. Marriage transformed a woman’s personal and social life. While a married woman was respected and had authority in her new house, she still could not control her own future. Her position was lower compared to her husband's. However, these documents lead to the crucial point: women were recognised in the Bactrian legal system as people with certain social rights. They had authority within their families and they had the right to witness a legal document.

Further Reading

- Azad, Arezou. “Living happily ever after: fraternal polyandry, taxes and “the house” in early Islamic Bactria,” Bulletin of SOAS 79, 1 (2016): 33–56.

- Ch’o, Hey. Hye Ch’o Diary: Memoire of the Pilgrimage to the Five Regions of India. Translated by Yung Hun-Sung et al., Asian Humanities Press, Po Chin Chai Ltd, 1984.

- Huseini, Said Reza. “Framing the Conquest: Early Muslim Domination of Bactria 652-750.” (PhD Diss. Leiden University, 2021).

- Khan, Geoffrey. Arabic Documents from Early Islamic Khurasan. Studies in the Khalili Collection; V. 5. London: Nour Foundation in association with Azimuth Editions, 2006.

- Lerner, Judith A., and Nicholas Sims-Williams. Seals, sealings and tokens from Bactria to Gandhara: 4th to 8th century CE. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2011.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas, Bactrian Documents from Northern Afghanistan II: Letters and Buddhist Texts. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum II, Studies in the Khalili collection 3. London: The Nour Foundation in Association with Azimuth Editions, 2007.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas, Bactrian Documents from Northern Afghanistan I: Legal and Economic Documents. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum II, VI; Studies in the Khalili collection 8. London: Nour Foundation, revised edition 2012.

- Si-Yu-Ki Buddhist Records of the Western World. Translated by Samuel Beal. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Trübner & Co. Ltd, 1906.

© Said Reza Huseini and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Said Reza Huseini and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.