Worms, noise and nuisances ad nauseam

What does the Old High German word nessia, found in early medieval medical charms, have to do with worms?

We are fortunate to live in a world in which old words for illnesses have slipped out of common parlance. While our forebears may have uttered the words ‘palsy’, ‘dropsy’ and ‘gout’ on a daily basis, nowadays these words have been banished to the realm of medical terminology or folk remedies. What is interesting from a historical perspective, though, is that the aforementioned words are all borrowings from medieval French (OFr. palesie, idropsie, goutte), taken over when French-speaking kings ruled the British Isles and brought with them a whole range of learned medical terms.

In this blogpost, I want to explore a German disease name, which, in my opinion, was also a borrowing from French, albeit from a significantly older type of French than that which supplied the loanwords for English. The etymology that I am discussing here would shed new light on a word that plays an important role in several of the oldest vernacular charms of the medieval continent. Furthermore, this etymology will illustrate the importance of taking into account the vernacular Romance dialects that were spoken in the Early Middle Ages—dialects that we do not find in written form, but which can be reconstructed through comparative linguistics.

Charm

The word in question is the Old High German word nessia, a vernacular word which is featured in medieval German text monuments ranging from the eighth to the twelfth centuries. The word nessia and its derivative nesso occur in the continental German charms pro nessia (southern German) and contra vermes (Low German), both of which are aimed at treating an undefined illness. The illness itself is addressed as nesso (presumably a personification of nessia) and the illness is commanded to exit the afflicted area of the patient:

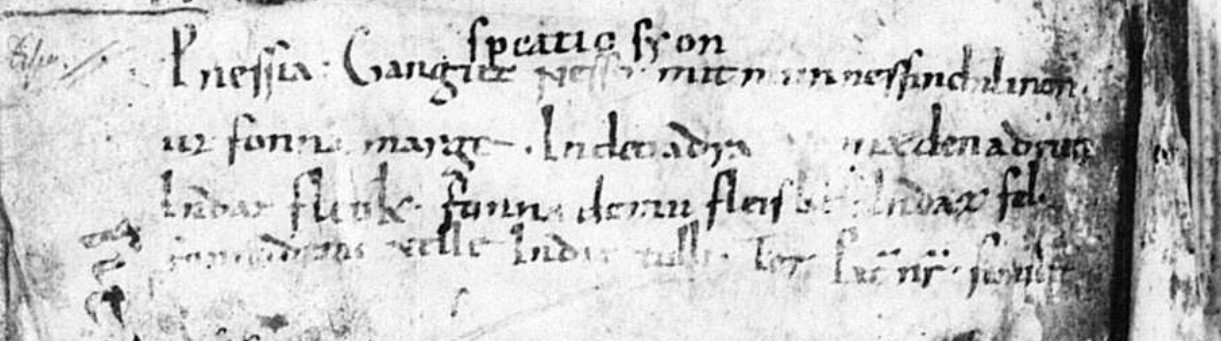

Pro Nessia (9th c. CE)

go out, nesso, with your nine nessinchilon,

out from the marrow into the bone,

from the bone into the flesh,

from the flesh into the skin,

From the skin into this arrow head.

Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 18524 b, fol. 203v

Since the Low German version of the charm characterizes the illness as vermes, the word nesso has often been interpreted as a word for ‘worm’, most recently in the Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Althochdeutschen (Lühr e.a. 2017: 908-909). The naming motive that would have led the text’s contemporaries to equate the word ‘worm’ with ‘disease’ is the medieval folk belief that small worms were responsible for all kinds of ailments and health nuisances. The word nessia is also found in a twelfth-century charm known as the “three angel charm”, in which three angels order a host of seven demons, several of which bear Old High German disease names, to refrain from plaguing a Christian soul.

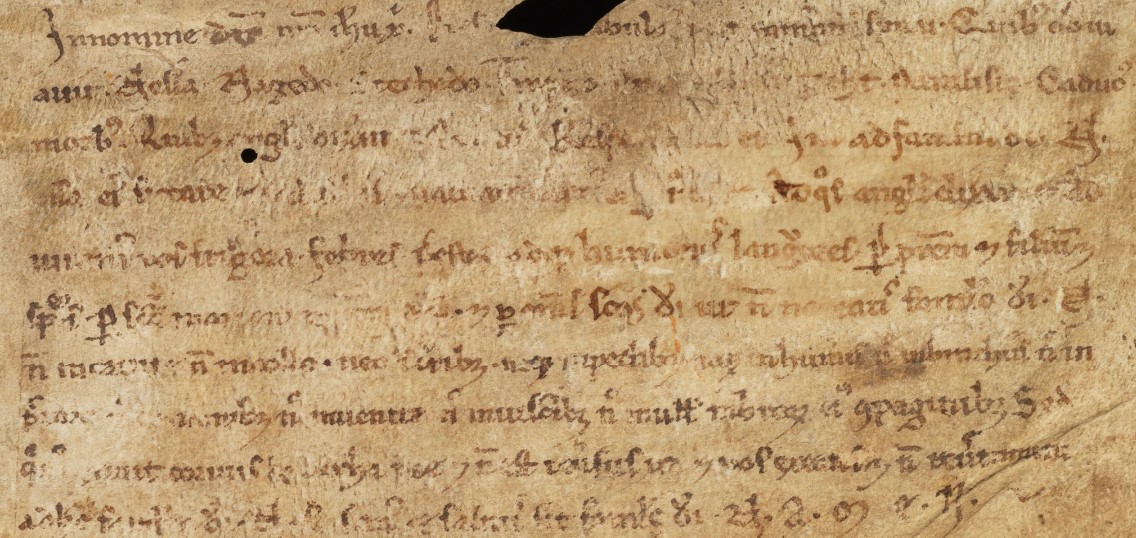

Three Angel charm (12th c. CE)

In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, three angels walked on mount Sinai. They came across Nesia, Nagedo, Stechedo, Tropho, Giht, Paralysis, and the falling sickness. To them, the angels said “Where are you going?”. They responded to them “We go to torment the bones of a servant of god…”

Luzern, Zentral und Hochschulbibliothek, P 34 4o, fol. 112v

The first of these demons is named nesia, a disease name that clearly matches the pro nessia title of the southern German charm. The word nessia also appears in the works of Hildegard of Bingen, who uses this disease name in the context of stomach pain. Surprisingly, this twelfth-century writer also gives the form nessedo, a word which she uses alternately with nessia in the same paragraph of the text (see Gloning e.a. 2010: 255). However, in the case of nessedo, it seems like we are dealing with a secondary abstract formation of a relatively recent date. Finally, it should be noted here that nessia, whatever its origin, seems to have been a generic term for illness, and this connotation must be taken into account when we go looking for an etymology.

Etymology

The etymologies that have been put forward so far for Old High German nessia range from the fanciful to the unlikely (see Zittera 2014). Germanic etymologies have been sought in the direction of a Germanic form *nasja (the asterisk signals a reconstructed form), ultimately related to Greek nosos ‘disease’. Another theory builds on the assumption that nesso is an Old Germanic word for ‘snake’ or ‘worm’ and connects it to the Germanic root *net- ‘to bind, to wind’, which is found in English ‘net’ (cf. Lühr e.a. 2017).

What is interesting, though, is that multiple scholars have rejected a Germanic etymology, and have argued for a Latinate origin instead. Some have contended that the word is derived from Latin nescius ‘unknown’ (cf. Latin nescio ‘I do not know’), thereby proposing that we are dealing with a semantic shift from “unknown disease” to “generic disease” (cf. Reiche 1977). Others have argued that the Greek word iskhias ‘hip pain’ was Latinized as nescias, but have offered no convincing explanation as to why an <n> appeared in front of the word. Neither explanation meets the modern standards of etymological scholarship and can safely be discarded. What is an additional problem, in my opinion, is that Latin in the Early Middle Ages was spoken primarily as a liturgical language and the majority of the population in the area in question, including most of the clergy, spoke Romance vernaculars. Any donor word of Latin origin entering Early Medieval German was therefore likely to be mediated through a vernacular Romance language.

What I want to propose is that the German word was instead borrowed around the seventh century from a vernacular Romance language, and, in particular, from an early form of French. The early medieval stage of the French language in question is called Gallo-Romance by comparative linguists. In this Gallo-Romance language stage, one of the generic words for disease must have been *næwsja, a vernacular development from the Latin word nausea (‘sea sickness, generic malady, discomfort’) which also lies behind the Old French noise (cf. FEW VII: 56-57). This Old French word noise can mean ‘illness, malady’, ‘dispute’ and ‘noise’ (the English word being a borrowing from French). It is my contention that the Gallo-Romance word offers us a perfect formal and semantic match with the German disease word. If this connection is correct, we have to assume that the Gallo-Romance word *næwsja was borrowed by the Germans as nessia, which is not very problematic, since Old High German did not have the sound [æw]. It is also worth noting that a younger form of the same Gallo-Romance word, in this case Old French noise itself, is probably reflected in Middle High German as Nösch ‘gout’ (see also Riegler 1938-41). If this second etymological connection is also correct, the French illness word seems to have made the jump across the language border twice.

Conclusion

Although the snake-worm etymology that philologists once associated with the Old High German words nessia and nesso is compelling in its simplicity and its ties to medieval folk belief, it is ultimately untenable, and an etymological connection of Old High German nessia to Gallo-Romance *næwsja seems far more likely. What is attractive about the etymology suggested here is that it places the transfer of the word from donor language to receiving language firmly in the realm of the vernacular and, in so doing, eliminates the problematic suggestion that Latin words of dubious origin might somehow be involved. This proposed etymology also fits well into the broader picture of widespread bilingualism in the border zone between the western and eastern parts of the Carolingian realm (cf. Kerkhof 2018). Furthermore, this case may serve to illustrate a more general point: that we often have to get rid of the Latin ‘white noise’ in order to arrive at a plausible Romance donor form for obscure Germanic lexis. Through this approach, reconstructed Romance can offer us valuable but often overlooked clues to etymological puzzles that, as of yet, remain unsolved.

Bibliography

[FEW] = Wartburg, W von. (1922-2003). Französisches etymologisches Wörterbuch: eine Darstellung des galloromanischen Sprachschatzes, Bonn: Klopp Verlag.

Gloning, H. R. Hildebrandt, & T. Gloning. (2010). Physica : Liber subtilitatum diversarum naturarum creaturarum. Berlin [etc.]: De Gruyter.

Kerkhof, P A. (2018). Language, Law and Loanwords in Early Medieval Gaul; Language Contact and Studies in Gallo-Romance Phonology. PhD-dissertation, Leiden.

Lühr, R., H. Bichlmeier, M. Kozianka, R. Schuhmann & L. Sturm. (2017). Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Althochdeutschen Band VI mâda - pûzza. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlag, Göttingen.

Reiche, R. (1977). Neues Material zu den altdeutschen Nesso-Sprüchen. Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, 59, 1-24.

Riegler, R. (1938-1941). Artikel Wurm. In: HdA. Hrsg. unter besondered Mitwirkung von E. Hoffman-Krayer und Mitarbeit zahlreicher Fachgenossen von Hanns Bächtold-Stäbuli. Bd 9. Berlin, Leipzig: Walter de Gruyter, 841-858.

Zittera, T. J. (2014). Magie und Mythologie: Der althochdeutsche Wurmsegen und die altisländische Überlieferung, Akademie Verlag.

© Alexia Kerkhof and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Alexia Kerkhof and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.