“Are you really sisters?” “No, we’re researchers!”

This summer, Godelinde Perk, Marly Terwisscha and Lieke Smits brought medieval sisters to life. How can research by performance lead to new insights?

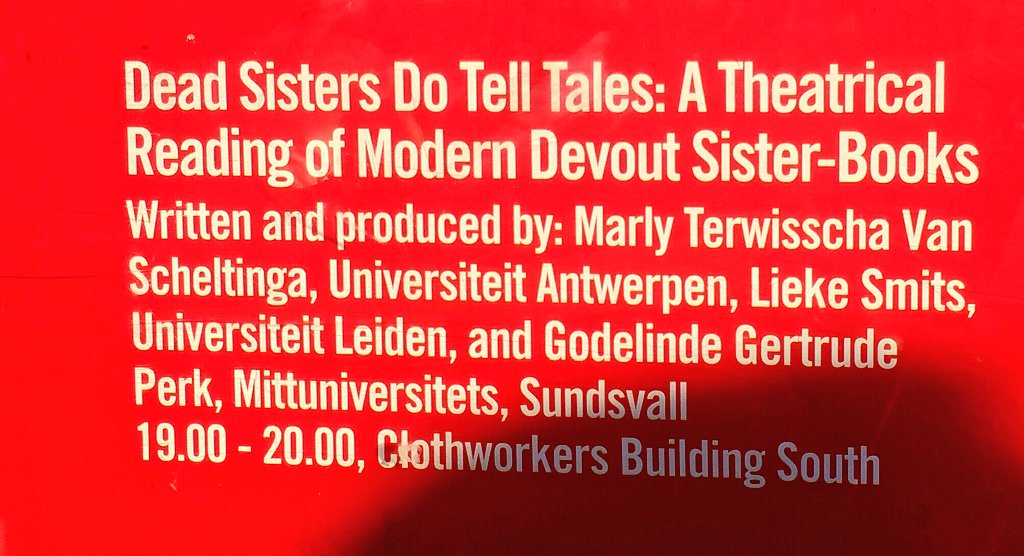

Every July, thousands of medievalists gather in the industrial city of Leeds in northern England. They convene for lectures, panel discussions, book and crafts markets, performances, and a dance. Besides organizing two sessions and presenting a paper, this year I also expanded my comfort zone by co-organizing and participating in a special event: a theatrical reading of modern devout sister-books (titled Dead Sisters Do Tell Tales), together with Godelinde Perk (Mid Sweden University) and Marly Terwisscha van Scheltinga (University of Antwerp). Through this event we wanted to do ‘research by performance’, hoping to provide the audience and ourselves with new insights in the written lives of medieval sisters. Before reflecting on the process of organizing such an event and the on the benefits and challenges of research by performance, I will first introduce the modern devout sister-books for those who are not familiar with the phenomenon.

Sister-books

Sister-books are collections of biographies or vitae of sisters, written about, by and for the sister of one community, serving as edifying literature. Several sister-books survive from female communities in the Low Countries belonging to the spiritual reform movement of the Devotio moderna. For our reading we chose to include excerpts from the sister-books of two of these communities: the convent of canonesses regular of Saint Agnes and Saint Mary in Diepenveen, and the lay community of Sisters of the Common Life at Master Geert’s House in Deventer. The biographies describe the lives of sisters who lived in the first half of the fifteenth century. The two books are somewhat different in nature: the Diepenveen book is focused on the sister’s noble descent and their denunciation of riches, while the Deventer book stresses the humble origins of the sisters (although many of them did come from wealthy burgher families), and the lives in former book a longer and modelled on saints’ lives, while the latter are shorter and more anecdotal.

Planning the performance

For us as researchers, the preparations were a vital part of the process. Working closely with the medieval texts led us to new insights in the sister-books. The preparatory steps involved choosing a theme, selecting and translating passages from the sister-books, creating a setting and writing a script. As a theme, we decided to explore how the biographies played a role in constructing community. This lens led to several questions, such as: what was the role of the lives of dead sisters in the community? In what ways did sisters have trouble fitting in? How were good and bad examples used to instruct and edify the members of the community? We noticed, for example, the importance of actively participating in the community. Warnings against wilfulness and singularity come forward in the biography of Sister Alijt Plagen of the Master Geertshuis, who was diligent, sensible and wise, but preferred being by herself:

During her life, she had been so singular, setting herself apart, and had turned her back on the community, which had often caused her superiors and the sisters difficulties. Therefore, our dear Lord had ordained that the communal prayers of the Holy Church and those of the sisters would not benefit her, nor help shorten her suffering in Purgatory as they do that of other souls. After all, driven by her own will and focusing on her own intention, she had failed to turn towards the community and had placed more trust in herself than in anyone else.

Many of the lives have a tripartite structure of pre-conversion life and conversion, ‘progress in virtues’ in the community, and deathbed scenes. We decided to adopt this as structure for our script, and select passages from each of the three categories. To add an overarching narrative, we created three characters telling these stories to each other, one of whom has recently joined the community and is looking for her place in the community. The other two sisters guide her in this process, for example warning her not to aspire to emulate the more miraculous events from the sisters’ life, but instead try to live a virtuous and humble life. By letting the sisters tell these stories to each other, we hoped to gain a sense of the oral contexts in which they originally functioned. With this in mind, when translating the texts we noticed that especially the biographies of the Master Geert’s House have a certain flow to them that seems closer to spoken than to written language, which would have facilitated communal readings during dinner, for example.

Performing as sisters

The actual performance was aimed at new insights for both us as participators and the audience. The empathy required for a performance drew attention to aspects that may go unnoticed in a more academic and dispassionate reading of the texts. In memorizing the script and telling it to an audience, we noticed the emotional force contained in the sister-books. A good example is the deathbed scene of Sister Geertruyt of Diepenveen, who was endlessly accused by the devil of a sin she had not properly confessed. When reading this out loud, the scene gains emotional strength through devices such as direct speech and repetition:

The sisters then said that she should trust in our dear Lord and firmly have faith in him. She said: “Yes I do.” Then it seemed like the devil agitated and frightened her more violently, just like he wanted to point things out to her that she did not know. Her face clouded over, and she cried out for a long time, loud and horribly: “Yes I do, yes I do”. She cried out so frequently, that the sisters do not know the number of her cries. Her voice resounded so loudly through the infirmary, that the sisters reading the Psalter in both corners of the room could hardly hear each other's verses. And this frightened and affected them so strongly that almost no eye was left dry.

Another layer of experience was added by our chosen setting; while telling these tales to each other, the sisters were doing handicrafts. This made us think of how the reading and telling of these stories throughout the day would have made them part of the embodied, daily lived experience in the community, conflating the lives and deeds of the past sisters with those living in the present and making them all part of one community. Moreover, hearing and telling these tales while holding a needle intensified the experience of hearing sentences such as “[Christ] wounded her heart through and through with a sharp thorn.” We might wonder whether the sisters made similar associations.

Engaging the audience

In the discussion with the audience after the performance we hoped to gain some insight in how engaging the biographies are when orally delivered. The Devotio moderna is often perceived as a very stern and strict movement aimed at interiorization of experience, disapproving of everything too bodily, too emotional and too mystical. Through our selection of fragments, we managed to surprise some members of the audience. We included, for example, a remarkably visceral vision by Sister Mette, in which Christ “took a handful of thistles and threw them on her bed, and rolled around in them naked, until he was all covered in blood.” An audience member noted that not only this selection, but also the fact that the sisters’ lives are literally brought to life, made him more appreciative of the Devotio moderna. Performances such as this could be a good way to interest non-specialists in historical topics.

Performing the sister-books did not only lead to a greater appreciation, but also drew the attention of the audience to aspects that come forward less prominently when reading the texts. An audience member noted that the performance and our facial expressions made them realise the importance of the social dynamics in such a tight-knit community. Moreover, it made the narratives more personal. Someone else noted that the passages on disobedience and gossiping, rather than exemplary and virtuous lives, are the most interesting to a modern audience. Bringing the sister-books to life made both the performers and the audience feel that the sisters’ emotions, social needs, personalities and flaws are just as human as ours.

Further reading

Translations of sister-books:

John van Engen (translator), “Edifying Points of the Older Sisters.” Devotio Moderna: Basic Writings, Paulist Press, 1988, pp. 121–36.

Wybren Scheepsma (translator), Hemels verlangen. Querido, 1993.

Secondary literature:

Anna Dlabačová and Rijcklof Hofman (eds.), De Moderne Devotie. Spiritualiteit en cultuur vanaf de late Middeleeuwen. WBOOKS, 2018.

John van Engen, Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life : The Devotio Moderna and the World of the Later Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Wybren Scheepsma, Medieval Religious Women in the Low Countries: The “Modern Devotion”, the Canonesses of Windesheim, and Their Writings. Boydell Press, 2004.